For Carlotta and Fiona, without whose incomparably greater

knowledge, generosity in sharing it, and time and hospitality in

Kabul and Islamabad, the task would have been beyond me; and for Michaela, my indispensable amanuensis and computer expert.

How can a small Power like Afghanistan, which is like a goat between these lions, or a grain of wheat between two strong millstones of the grinding mill, stand in the midway of the stones without being ground to dust?

Amir Abdur Rahman, on Afghanistans relationship

with Britain and Tsarist Russia, 1900

Contents

Kashmir, Pakistan December 1971

Since Partition in 1947, when British India, the Jewel in the Crown of Empire, attained independence and was divided into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan, the two countries have been at one anothers throats. The bloodletting at Partition was horrific. About 10 million people were displaced amid scenes of bloodshed and violence which led to the deaths of another half a million, and the two new nations fought the first of their wars over Kashmir immediately afterwards.

Renowned for the beauty of its lakes and mountains, a romantic spot where in the days of the Raj young British newlyweds would spend their honeymoon on a houseboat, Kashmir was politically a time bomb. It was, in many ways, a microcosm of the old India. The ruler, a maharajah, was a Hindu. After Partition, he opted to join India, under pressure from Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, himself of Kashmiri origin. But most Kashmiris were Muslims and when they rebelled, Nehru sent in the army. The first Indo-Pakistani War led to another partition, the capital Srinagar and the famous lakes falling to India, and Azad (Free) Kashmir going to Pakistan.

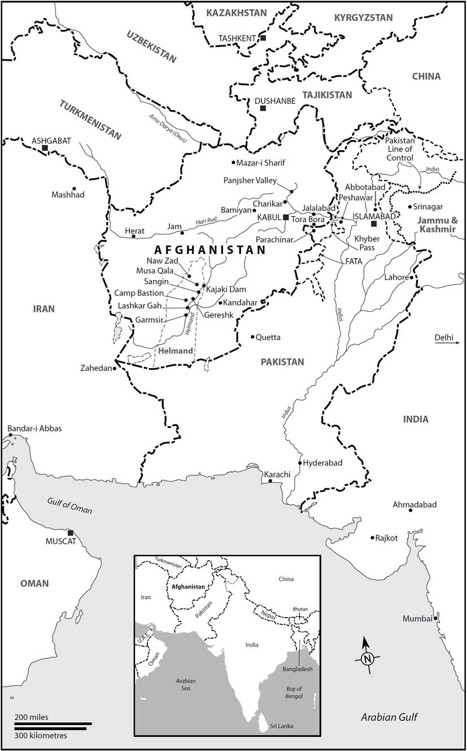

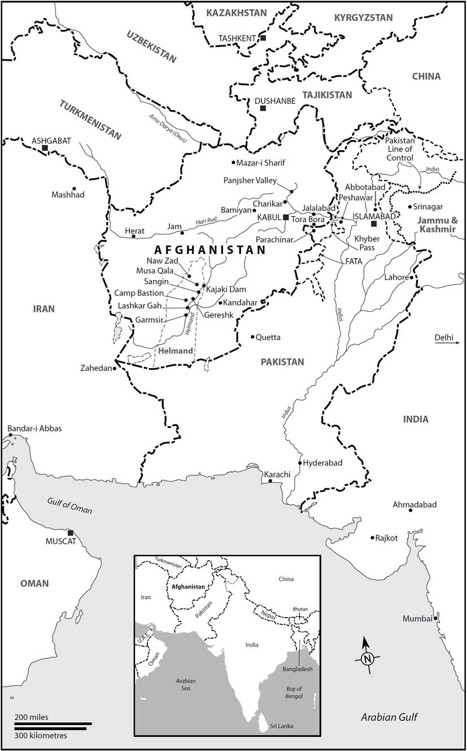

That was in 1948. Twenty-three years later, I found myself flying to Kabul en route for Pakistan on the outbreak of the Third Indo-Pakistani War, on 3 December 1971. Pakistan had closed its airspace and the only way in was by air to Kabul and then by road over the Khyber Pass to Peshawar.

One of the results of Partition had been to make Pakistan virtually ungovernable. Twelve hundred miles of hostile India divided East from West Pakistan and, apart from religion, they had little in common. Economically and politically West Pakistan was the dominant partner. The capital, then, was Karachi. Inevitably, East Pakistan developed an inferiority complex. To make matters worse, a disastrous cyclone struck the East in 1970. Elections that December returned the Pakistan Peoples Party to power in the West and the Awami League to power in the East. A dispute broke out as to who should rule, strikes followed and then a revolt in the East, which declared independence as Bangladesh. India backed Bangladesh and declared war on Pakistan. The outcome was predictable. Outnumbered three to one, and fighting a long way from home, Pakistan not only lost half its country but suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Indians. A whole army of nearly 90,000 men was taken prisoner and morale plummeted.

In Islamabad, I happened to meet an old friend, General, later President, Zia ul-Haq. He was like a man bereft. This latest debacle, Pakistans third defeat in three wars, would leave deep wounds and lasting bitterness. Having completed the spectacular journey through the mountains of Afghanistan and over the Khyber we spent the night in Peshawar where there was a blackout and drove south the next day. When my ITN crew and I reported to the press office at army headquarters, Rawalpindi, we were told we could go on an army trip to Kashmir the next day.

We were taken to the front line. There was very little action. The Pakistanis and the Indians had a standard drill, the friendly artillery major in charge informed us. Every morning the Indians would shell the Pakistan lines, and every afternoon the Pakistanis would return fire. Feeling we ought to film some aspect of this war, having taken such trouble to get here, I asked the major what time he would be firing back.

Oh, about four oclock, he said.

I looked at my watch. Unfortunately, theyre taking us back at 3.30.

Oh, no problem, he said helpfully. We can easily bring it forward half an hour and wake them up a bit early. He smiled to show it was a ritual, nothing more.

The BBC, I remember, were also keen to film a bit of the action. We all chorused our approval. Five minutes later the obliging major sent ten or twenty shells hurtling across the sky to explode in Indian territory ten miles away. Will they respond? I asked.

No, no, he said with a laugh. Tomorrow morning.

Otherwise, there was no action on the Kashmir front. But in the months and years ahead, the Pakistan Army would recruit, arm and train many hundreds of guerrillas to fight in Kashmir. For them it would not be a ritual, but a bitter war. As the guerrillas became more experienced and more lethal, they would eventually carry out attacks like that, many years later, on Mumbai. The bitterness would grow and the chances of a settlement in Kashmir would become increasingly unlikely. But without such a settlement, it is difficult to see how peace between India and Pakistan can ever be established.

This book is about Afghanistan. But, as I will try to show, the key to that war lies at least partly in Pakistan, and in the Kashmir problem. We, in the West, have been slow to grasp that simple truth. Even the United States, with its vast resources, both material and intellectual, has not found an answer to the riddle: how do we persuade Pakistan to abandon its support for the Taliban and make peace with India? I do not pretend to know the answer, but I know it is important we apply ourselves to finding it.

Early Battles

Im sending four Special Forces people with you to make sure youre safe.

General Zia, Rawalpindi, 1984

I first met Zia, then a brigadier, in Amman, where he was deputy head of the Pakistan Military Mission to Jordan. It was just after Black September, 1970, when, after months of provocation and mounting fears of a PLO (Palestine Liberation Organisation) coup, the pro-Western King Hussein finally took action against them and their leader, Yasser Arafat. A close confidant of the King, Zaid Rifai, later Ambassador to London and Prime Minister, described to me how fraught the situation then was: The fedayeen had almost taken total control of Amman; the [Jordanian] Army was deployed in the Jordan Valley against Israel. On 15 September a parliamentary delegation went to see Arafat in an attempt to have him and his forces abide by Jordanian laws and leave the capital... if his real aim was to mount operations against Israel. Arafat told the parliamentarians that the situation had gone out of his hands, that he could not control all the fedayeen and that all he could do was to offer King Hussein twenty-four hours to leave the country.

When the parliamentary delegation reported this to the King, he immediately formed a military government and declared martial law. The commanding general telephoned Arafat and gave him an ultimatum: leave the capital with his forces or the army would drive them out. Arafat refused, so on 17 September the army was ordered to move against the fedayeen, of whom there were 70,000, according to Zaid Rifai, dug in all over the city. In the ensuing battle, the commander of the 2nd Armoured Division and his deputy were badly wounded and King Hussein asked Zia, who had once been a tank commander himself, to take over. We flew Zia in a helicopter to the north [where the Syrian armour, camouflaged as PLO tanks, had invaded] and he took command, Rifai recalled. Many observers believe Zia played a key role in the defeat of the PLO and Zia told me that the first person to congratulate him when he deposed Bhutto, the authoritarian Prime Minister of Pakistan, seven years later, was King Hussein.

Next page