Copyright 1994 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1996

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marling, Karal Ann.

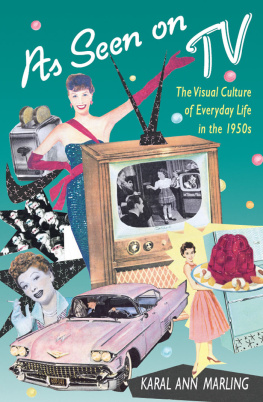

As seen on TV : the visual culture of everyday life in the 1950s / Karal Ann Marling.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-674-04882-2 (cloth)

ISBN 0-674-04883-0 (pbk.)

1. United StatesSocial life and customs19451970.

2. Television broadcastingSocial aspectsUnited States.

3. Popular cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century.

I. Title. II. Title: As seen on television.

EI69.02.M3534 1994

973.92dc20 94-2814

Designed by Gwen Frankfeldt

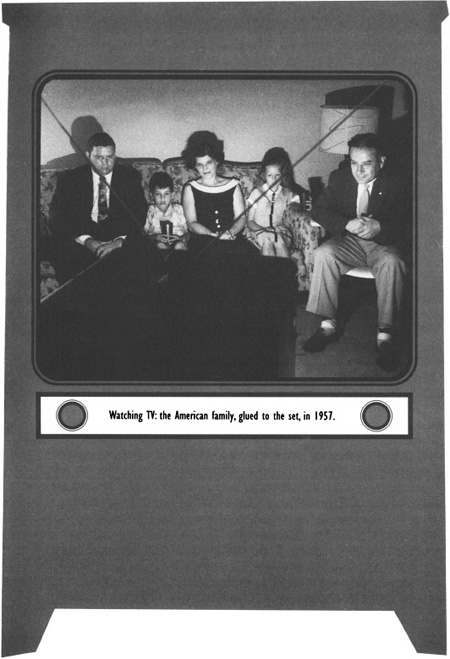

G iant (1956) is one of the great, big-screen epics of the 1950s. Its got everything. A radiant Liz Taylor. Rock Hudson in his first major role. James Dean, teen idol, wearing blue denim jeans, in his last. Dean died in a car crash during post-production work on the film. There were only two people in the fifties, remembers the actor Martin Sheen. Elvis Presley, who changed the music, and James Dean, who changed our lives.

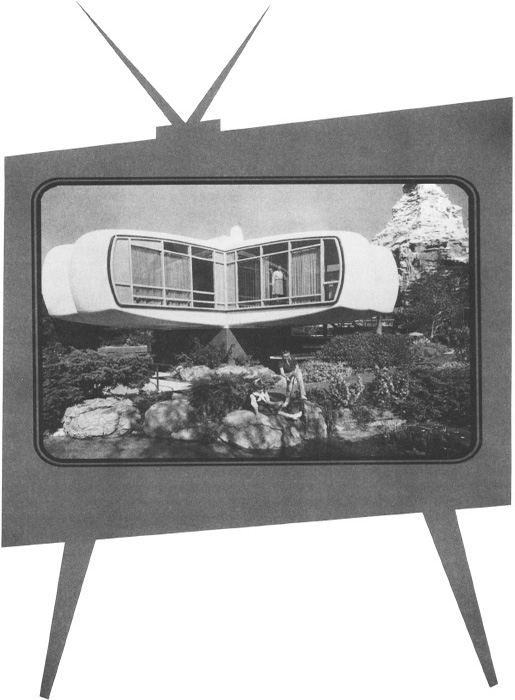

Giant is long, too. Gone with the Wind, to which Louella Parsons, for one, compared George Stevenss dynastic saga of oil, prejudice, and married life in the American West, is only thirty-seven minutes longer. And the scope is equally vast: cultivated Maryland belle Leslie Lynnton (Taylor) is wooed by raw Texas rancher Bick Benedict (Hudson) in the flapper era, but by the end of the story, as the couple sit together minding their grandchildren, the 1950s have arrived with a vengeance. The big house on Benedicts spreada gloomy, three-story Victorian horror that Warner Brothers shipped from Hollywood to Marfa, Texas, in pieces on five railroad flatcarshas become a white-and-gold, ranch-house-moderne fantasy of sectional sofas and recumbent cocktail tables, with a picture window, a swimming pool, a patio, and a built-in barbecue out back.

In the form of Cadillacs, oil wells, private planes, mink stoles, twin beds, and dresses from Neiman-Marcus, civilization has clearly tamed But others thought Giant was about new money, about diamond rings on fingers still puckered from the washtub.

Edna Ferber, who wrote the novel upon which Warner Brothers loosely based Giant, was fascinated by the Texas nouveaux riches. She did her research in Texas in 1948 and 1949, when the place was awash in new oil money; for Ferber, the Lone Star State became a metaphor for the postwar United States and its material prosperity. Her description of the company town where the Chicano ranch hands and their wives shop attests to an abundance that transcends old class barriers, even as Ferber mocks the products on display. Plate glass windows reflected, glitter for glitter, the dazzling aluminum and white enamel objects within, she writes of the show windows. Vast refrigerators, protean washing machines, the most acquisitive of vacuum cleaners.... Plastic things, paper things, rayon things. Gadgets.

The filmscript is another matter, though. Written around a TV set during the Army-McCarthy hearings, it attacks contemporary social issues implicit in but hardly central to the novel. The Mexican workers on the Benedict ranch, for example, stand for all people of color, and for the civil rights movement in the year of the Montgomery bus boycott: the movie ends with a vision of future racial integration, two Benedict heirs, one white and the other brown, sharing a single playpen (in case the point is not abundantly clear, the children are juxtaposed with a white lamb and a Black Angus calf). The American family will solve the largest national problems at the level of father and mother and children, ranch house and Cadillac. Jett Rink (Dean), the villain of the piece, is an orphan, an outsider who pines for the amenities of house and home but winds up the unhappy owner of a fancy, empty hotel.

Despite changes in emphasis, however, the rich, textural qualities of Ferbers original persist, mainly in the detailsin the set decoration by Boris Levin, and the flouncy pastel dresses by Moss Mabry. And the burnished look of the film, especially in the chic interiors, The movie is a celebration of House Beautiful interiors over exteriors, Liz Taylors domain over Rock Hudsons, perhaps, the bright, modern home and all the artful paraphernalia that fills it over issues, 9-to-5 careers, and an inconvenient, dark, and dingy past.

In his pioneering study of Hollywood films of the 1950s, Peter Biskind argues that the pictorial emphasis on the house puts the consciousness of Taylors Leslie at the very center of Giant. She is the Queen of Hearth, and Mother (not Father) knows best on the Benedict ranch. It is the cinematic housewife, he says, who shapes and finally controls the mans environment and his values. But secure in their artfully contrived setting, Leslie and Bick dont seem very different by the time the 50s come to Texas: they are full domestic partners, both of them equally at ease with the postwar gadgets, the low-slung living room suites, with tail fins and togetherness.

Despite the classical man-and-wife bickering and their ultimate renunciation of the two-ton, forty-foot mobile home that literally propels the plot, Desi and Lucy (as newlyweds Nicky and Tacy Collins) seem delighted with all of the above, too, in The Long, Long Trailer of 1954. If Giant and movies like it tried to outdo TV in spectacle, sumptuousness, scale, and stereo sound, The Long, Long Trailer represents a concession to the popularity of I Love Lucy and small-screen, middle-class, family sitcoms. MGM made the movie in June and July of 1953, when the Arnazes weekly comedy series was on hiatus and at a time when the studios own contract players were still forbidden to appear on television. The idea was to wean addicts away from the And as in the Texas of Giant, the Western landscape through which the honeymooners drag their home on wheels pales in comparison to the trailers colorful interior, replete with built-in sectionals and appliances, and the cameras pastel views of luxurious roadside trailer courts which are really instant, overnight suburbs, with swimming pools. If the Benedicts are upwardly mobile, beyond the wildest dreams of the audience, the Collins family is simply mobile. But in both cases, the viewers eye is seduced by creature comforts, all shiny and new.