2015 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Anderegg, Michael A.

Lincoln and Shakespeare / Michael Anderegg.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-2129-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2148-4 (ebook)

1. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Books and reading.

2. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Influence. I. Title.

E457.2.A543 2015

973.7092dc23

2015023665

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10987654321

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

PREFACE

In an early scene of John Fords 1939 film Young Mr. Lincoln , Ann Rutledge responds to Abes recital of his inadequacies by saying, But youve educated yourself, youve read poetry, and Shakespeare, and now law. An imagined Lincoln can be counted on for a few lines from Macbeth or Hamlet or Julius Caesar at the drop of his stovepipe hat, even if neither the context nor the tone seems quite right.

John Drinkwater, in his 1918 play Abraham Lincoln, invents this unlikely exchange between the president and Secretary of State William Seward:

LINCOLN: There is a tide in the affairs of men Do you read Shakespeare, Seward?

SEWARD: Shakespeare? No.

LINCOLN: Ah!

Never mind that the real Seward, who had enjoyed a formal education the president lacked, would almost certainly have recognized the allusion. At least the line from Julius Caesar is one that Lincoln, according to his law partner, William Herndon, particularly liked to recite. At another point in Drinkwaters play, John Hay reads aloud to Lincoln the passage beginning Our revels now are ended and ending rounded with a sleep from The Tempest, a moment further elaborated in the 1952 Studio One television adaptation of Abraham Lincoln, which has Mary read the lines as Lincoln silently mouths the words. At the end of the teleplay, as Lincoln walks off to his destiny at Fords Theatre, the camera closes in on a page from (one presumes) Shakespeares works on a reading stand as in voice-over Lincoln recites over rising music, We are such dreams as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep (slightly fumbling the lines). Poetic license, perhaps, but not unreasonable.

In other Lincoln-inspired poetry and prose, the Shakespeare reference can be inappropriate or simply puzzling. For poet Delmore Schwartz, identifying Lincoln with Hamlet is a way of debunking him: he calls Lincoln This Hamlet-type and adds,

O how he was the Hamlet-man, and this,

After a life of failure made him right,

After he ran away on his wedding day,

Writing a cowards letter to his bride.

The Lincoln of Irving Stones 1954 novel Love Is Eternal, speaking of the ambitions of his rival Stephen Douglas, comments, I can only think of the line in Julius Caesar: He doth bestride the narrow world like a Colossus, and we petty men walk under his huge legs, and peep about to find ourselves dishonorable graves. a somewhat bizarre reference to a play, A Midsummer Nights Dream, that Lincoln very probably had not read and almost certainly never saw.

The screenplay by Tony Kushner for Steven Spielbergs 2012 film Lincoln several times has the president quote Shakespeare, each time grabbing the words more or less out of thin air. Speaking to Secretary of State Sewards factotums, Lincoln is made to say, We have heard the chimes of midnight, Master Shallow (slightly misquoting Henry IV, Part 2 ); all he means is that time is getting short. When Seward tells him that he has to choose between passage of the Thirteenth Amendment or accepting a Confederate peace, Lincoln, quoting from Macbeth , somewhat petulantly replies,

If you can look into the seeds of time

And say which grain will grow and which will not,

Speak then to me,

a convincing enough allusion given Lincolns well-known fondness for the play, though it is hard to imagine that he would address his secretary of state with Macbeths words to the Weird Sisters. A more meaningful moment comes in the conversation with Elizabeth Keckley, a former slave and Mary Lincolns dressmaker and friend, when Lincoln paraphrases a line from King Lear : Unaccommodated, poor, bare, forked creatures such as we all are, associating himself, and all mankind, with the people he has helped rescue from slavery. When he recounts a dream, Lincoln cites Hamlet : I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams, an oblique way of alluding to Lincolns oft-remarked-upon fascination with his own dreams.

The impulse of novelists, poets, playwrights, and filmmakers to associate Lincoln with Shakespeare, sometimes felicitous, sometimes awkward and self-conscious in execution, is founded on a substantial body of evidence. Lincolns affection for Shakespeares plays was frequently mentioned by his contemporaries and has become a notable part of Lincoln lore, helping define his personality and character in a manner overlapping with but distinct from his penchant for jokes and comic stories. Throughout his life, and particularly in the years of his presidency, Lincoln turned to Shakespeares plays not only for the pleasure he took in the poets language and fund of dramatic incident but also for relief from the cares of state and even for solace when faced with personal disappointment. His Shakespeare was, inevitably, a partial Shakespeare, a Shakespeare adopted early on as an honorary American, shaped by the sensibilities of a new world and made palatable to the democratic, leveling impulses of the American nation. The tragedies and histories, in particular, appealed to Lincoln at least in part because they appealed to America. These plays again and again illustrated the dangers of inordinate ambition, the devastation of civil war (no less than eight plays are concerned, directly or indirectly, with the Wars of the Roses), and the corruptions of illegitimate rule. In addition to these thematic issues, the oratory of Shakespeares characters, the speeches and soliloquies, were well suited to a highly oratorical age. Politicians and other public figures quoted or cited Shakespeare in their speeches and writings. Lincolns interest in Shakespeare can only be understood fully when placed in the context of nineteenth-century American culture.

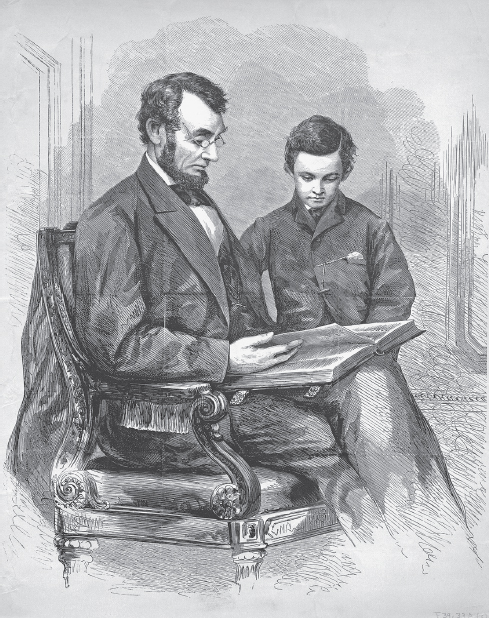

Although quotations from and citations to Shakespeares plays are not abundant in Lincolns own writings, he often read from and alluded to Shakespeare in conversation with friends, secretaries, family members, and other visitors and bystanders who recorded their impressions in diaries and letters as well as, in later years, essays and memoirs. We also have testimony to Lincolns interest in Shakespeare from newspapers and other more or less official sources contemporary to the events they describe or report. In the pages that follow, I strive to separate plausible evidence from myth without undermining my central contention that Lincoln was throughout his life fascinated by and engaged with Shakespeares plays. I then explore the question of how Lincoln came to know Shakespeare, including a consideration of what editions of the plays he may have owned or had access to at various points in his life. Particular interest is paid to Hamlet and Macbeth, the plays that figured most prominently in Lincolns imaginative life. I explore as well various aspects of nineteenth-century Shakespearean theater as Lincoln might have experienced it from his youth to the years of his presidency. Here, I examine what theatrical venues would have been available to Lincoln in Springfield as well as in other places to which he traveled before 1861, including New Orleans and Chicago. The American theater in general underwent a significant transformation in the period from when Lincoln would have first encountered it to his years in the White House. As a young man on the frontier, he would have had small occasion or opportunity to attend the theater; by the time he was elected president, theater all over America was a thriving institution.