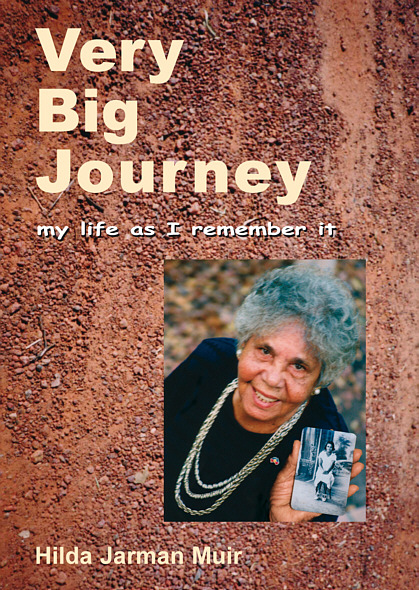

Very Big Journey

Readers of this work should be aware that if members of some Aboriginal communities see the names or images of the deceased, particularly their relatives, they may be distressed. Before using this work in such communities, readers should establish the wishes of senior members and take their advice on appropriate procedures and safeguards to be adopted.

Very Big Journey

My Life As I Remember It

Hilda Jarman Muir

First published in 2004

Reprint 2010

Aboriginal Studies Press

for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601

The views in this publication are those of the authors andnot necessarily those of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

The publisher has made every effort to contact copyright owners for permission to use material reproduced in this book. If your material has been used inadvertently without permission, please contact the publisher immediately.

Hilda Muir, 2004

Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-In-Publication Data:

Muir, Hilda Jarman .

Very big journey : my life as I remember it.

ISBN 0 85575 397 8.

ISBN 9780 85575 5521 8 (PDF ebook).

1. Muir, Hilda Jarman. 2. Aborigines, Australian - Women -Northern Territory - Biography. 3. Aborigines, Australian -Removal. I. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. II. Title.

994.2904092

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Cover Photograph by Sue Wicks

Cover Design and layout by Fat Arts

Editorial work by Melissa Lucashenko and Felicia Fletcher

Produced by Aboriginal Studies Press

Foreword

This is the life story of Hilda, who journeyed as a young child from her country in Borroloola to the newly established town of Darwin. The journey was on horseback, and her cultural ties and the bond to her mother were severed, forever. Hilda was like many children brought to someone elses country as a result of the stolen generation policies. She survived the hardships of growing up and raising a large family, and a husband who volunteered for World War Two and on return was, like many soldiers, an angry personality when on the hops. He was also a man full of charm and wit. He died during Cyclone Tracy which devastated Darwin in 1974. I became closely attached to Hilda during the mid-1970s when her daughter Cissie and I, along with our children, dared to enter tertiary education in Adelaide. Hilda, depressed after the cyclone, was soon to rise again. She became fascinated with all spheres of the arts and took advantage of her many trips to Adelaide to visit the theatres. NAIDOC in Adelaide was always special for Hilda; to join in the marches, attend the speeches, and then dress up for the Nunga Ball.

Hilda had been a very depressed widow at first a woman who had been totally dependent on her lifelong partner to be there always. But Hilda has grown as a result of her hard times. Now in her eighties she is younger than ever. When I started to do research for a book which included Hildas background it stimulated many reflections and much questioning. For Hilda, the discussion of the stolen generation story nationally gave her impetus. She was adamant she wanted to tell her story for her children, but also have a published version for the mainstream community. An application was made to the Aboriginal Arts Board for a grant to cover expenses. A recruit was needed; someone who would assist Hilda and she chose an old mate in Adelaide. Both travelled to Borroloola and other significant places in the Top End. At a later date the manuscript was assisted by Melissa Lucashenko with the advice and assistance of Jackie Huggins from AIATSIS. A manuscript was created and is now ready for publication. A great achievement. Congratulations Hilda!

Barbara Cummings

ATSIC Chairperson

Darwin

June, 2003

Preface

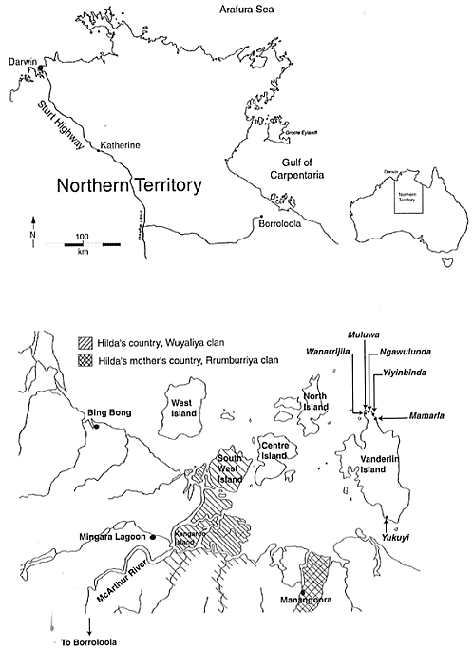

Hilda Muir was born at Manangoora, near the small outback town of Borroloola in about 1920. It was an era of pearl luggers and bullock drays, and, as a child, Hilda heard graphic first-hand accounts about the dangers of wild white men and their guns. For the Yanyuwa people, the sound of shooting still resonated through their homelands, which were only then coming under the firm control of white authorities. Hilda was born, in other words, on the very frontier of modern Australia.

Hildas early life was spent roaming the Gulf Country on foot, hunting and gathering bush foods for sustenance, as her people had done for millennia. Her mother was a Yanyuwa person, and therefore so was Hilda, who was known to the clan as Jarman. It mattered little that her father was an unknown white man. This small girl had a name, a loving family, and a secure Aboriginal identity. Under the policies of the day, though, Hilda was removed by the Borroloola police at eight years of age to the Kahlin Home for half-caste children in Darwin. She would never see her mother again. Like other children of mixed Aboriginal/white or Aboriginal/Asian descent, Hilda was deemed more intelligent and more capable than her full blood Aboriginal relations. Children of mixed-race were then seen as tragic but teachable. They were removed, institutionalised, trained for manual labour, and usually sent into white society with few skills and fewer prospects.

Hilda survived the experiences of the Kahlin Home. As an adult she fled the Japanese bombing of Darwin, lived through Cyclone Tracy, and bore ten children to a beloved husband. She discovered the excitements of city living, and became addicted to overseas travel. As an old lady, in 1995 she presented the High Court of Australia with a writ on behalf of her fellow stolen generations children, asserting that the government removals of mixed-race children had been not only immoral, but illegal. Most momentous of all in Hildas own eyes, in 2000 she finally went home to her Yanyuwa land and was recognised by her own people as a jungkayi: an owner and custodian of that country. This is the story of Hildas bush childhood, and of her removal from a family who had always claimed her and loved her. It is a story of how institutions can exert a terrible power over the children who inhabit them. It is also the story of how the twentieth-century policy of assimilation failed. Hilda married another half-caste Aborigine, William Daniel Muir. Today Hilda Muir, her Aboriginal children, their children, and those childrens children are all living reminders that governments cannot always shape human lives in the ways they might wish. The book has been written in language which can be read and understood by the stolen children themselves. Words such as fullblood and half-caste, though considered offensive by many Aboriginal people today, have been used because of the need for historical accuracy.

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.