This edition is published by BORODINO BOOKS www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books borodinobooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1943 under the same title.

Borodino Books 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

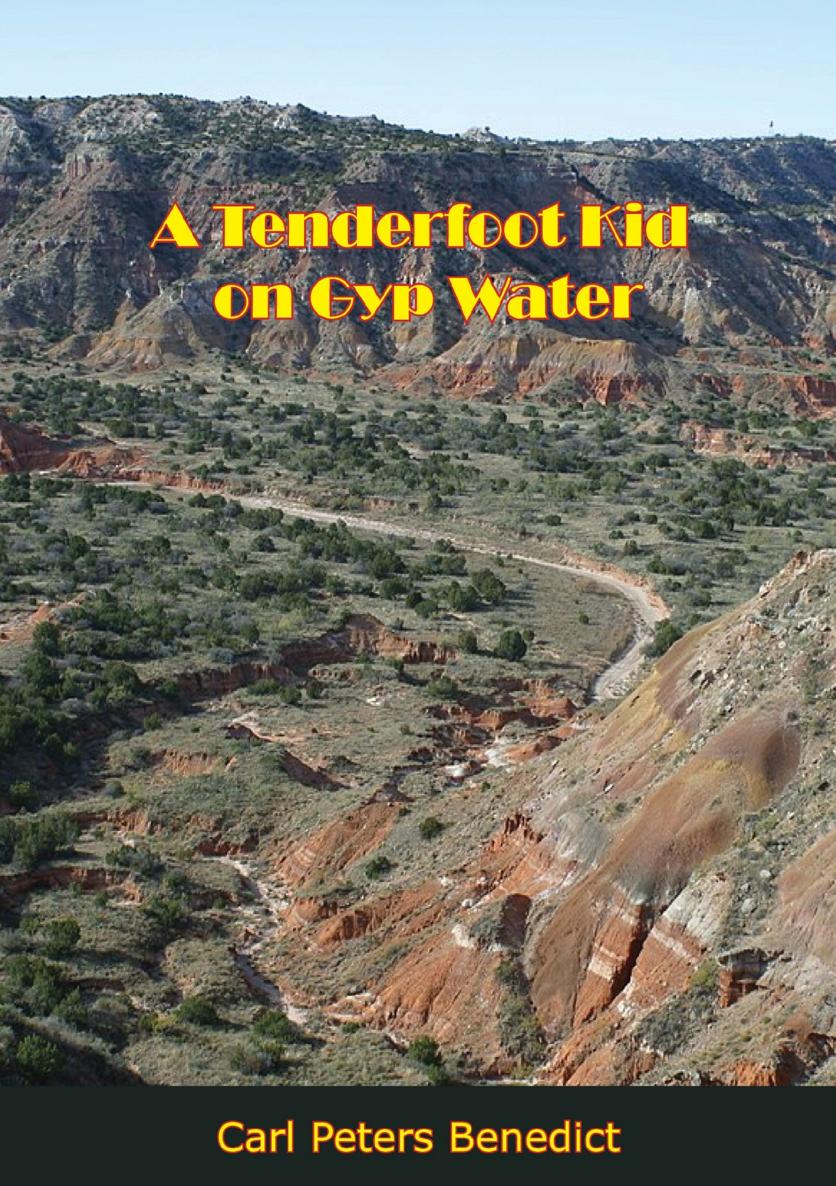

A TENDERFOOT KID ON GYP WATER

by

CARL PETERS BENEDICT

Introduction by Frank Dobie

1943

INTRODUCTION

by J. FRANK DOBIE

IN 1841 THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS entered into a contract with W. S. Peters, of Louisville, Kentucky, and associates to settle 600 colonists in Texas. Married settlers were to be granted a section of land each, unmarried settlers a half-section, and the colonizers themselves ten sections for every one hundred colonists brought in. In subsequent years the Peters contract was extended and modified. The Peters colony on the Trinity River had a history not happy.

In 1877 H. J. Peters, son of the colonizer, set out from Kentucky to settle on Peters Company land. It was west of the old Peters colony; it was on the frontier. In the wagons with H. J. Peters and his wife and two sons came his daughter, Mrs. Adele Peters Benedict, and her two sons, Harry Yandell, born in 1869, and Carl Peters, born in 1874. The father and husband, Joseph E. Benedict, had preceded the family migration and established a small ranch near Fort Belknap in Young County. He had fought for four years in the Confederate Army and risen from private to captain. In Texas everybody knew him affectionately as Cap. In love of horses at least, Carl was to take strongly after him, while Harry Yandell, though a great lover and student of nature, was to take more after his mother.

The Peters family, the Benedicts continuing to live with them, located on a half section of land fronting the Clear Fork of the Brazos River. The big house they built out of lumber freighted from Fort Worth was in time found to be exactly bisected by the line separating Young and Stephens Counties. The few cattle they had they were for a long time afraid to turn out of the pens at night for fear the cowboys would drive them off. With great labor they built a rock fence around part of their land. They grubbed mesquite from and plowed up land utterly worthless for anything but grazing. The country was, and still is, mostly a ranch country. It was not fenced until bob wire came in years after the arrival of the Benedicts.

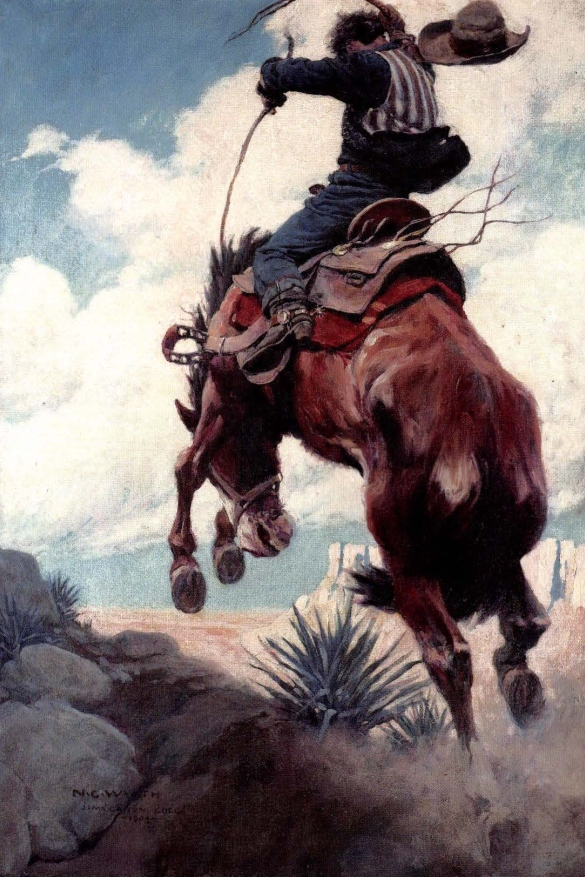

Graham, in Young County, where cattlemen in 1876 organized what is now nationally known as the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association, was the trading point. Coming out of Graham one day in a hack, Carl Benedict and others of the family heard yells and shots and, looking back, saw six cowboys tearing down the road, riding like drunk Indians. The hack was pulled to one side to give them a clear passage. Carl wanted to be a cowboy.

The wagons had brought a thousand good books from Kentucky. Mrs. Benedict read to her boys, taught them. They went to school in Graham a winter. For four winters Carl rode horseback to a little school at Eliasville. Meantime Harry Yandell (H. Y.) was studying farther afield, taking the road that led him to a Ph.D. from Harvard, then to professorship, deanship and finally presidency at the University of Texas. My mother and Yandell sent me to Austin one year, Carl Benedict remembers, but I hated to live there so bad and loved the home place and the cattle and horses so much that I begged them to let me stay at home the next year. I told them that if they would let me stay at home I would learn to cook biscuits for my mother, who was sick and not able to cook. She died in November of 1894, my father having preceded her. We were very sad for a long time after that. The spring and summer before this, however, were perhaps the happiest time of my life, the cowboy days on the open range about which I have written my book.

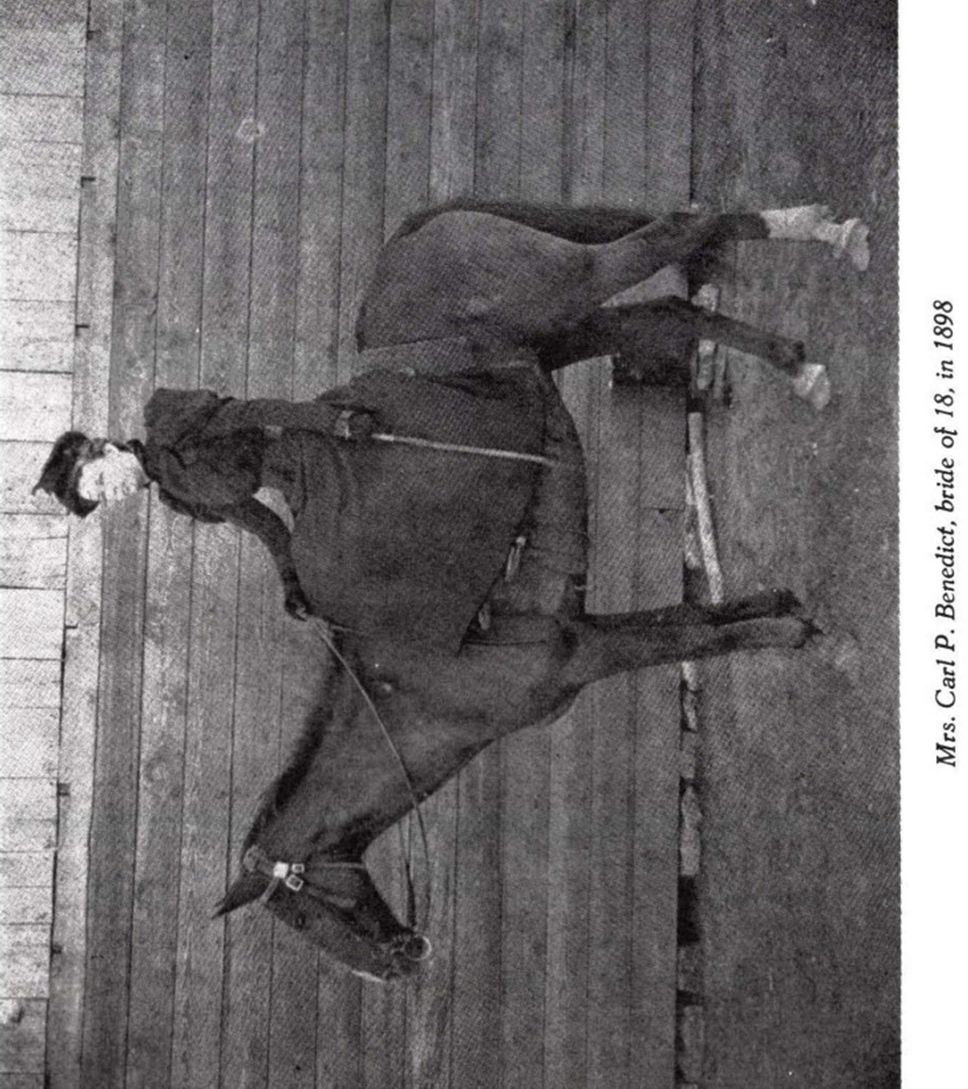

In 1898 Carl P. Benedict married eighteen-years-old Mamie Caudle, from Haskell County. Six years later they went farther west and fought sandstorms and drouths for thirty years, went broke twice and raised our children, got on our feet again. One of these children, the youngest, Carl P., Jr., had been in the Naval Air Service for nearly fourteen years and was at Cavite when the Japs took it He got out of Corregidor in a submarine and made it to Australia. The second boy, Ed, works at the bomber plant near Fort Worth. The oldest son, Norman, ranches near Melrose, New Mexico.

In the spring of 1933 I was in the cow and oil town of Midland, Texas, to make a commencement speech. Death will have no added sting for me if I never make another. The morning after it was over I was having a bully time talking to some of the old-timersBill Gates, who while poisoning prairie dogs once saw an old rattlesnake on the edge of a dog hole swallow a passell of little ones; Brooks Lee, who drove a herd to California in 1869; hearty Spence Jowell, and others. Then I met a little grey man whose features and behavior showed that he had spent many steady years on drouthy ranges without ever making enough money to speak of and also without having let adversity dim out the bright spark of life that nature had lighted for him long before he was born. He was very shy and diffident in turning over to me a manuscript that a Texas printer had offered to publish if somebody would pay for the printing. He had a vague and very modest idea that I might interest a real publisher in putting it out.

Even at first sight the little grey, shy man did not seem a stranger to me. He looked like and in many ways reminded me of his brother, H. Y. Benedict, whom I had known many years and whom I loved and also not infrequently disagreed with. I read the manuscript with pleasure, and even though it needed revising, thought it worthy of a publishers consideration. No publisher that I offered it to, however, agreed with me. I have read plenty of range narratives from their presses that seem to me less valid and vital.

![Helen Peters [Helen Peters] - A Piglet Called Truffle](/uploads/posts/book/140179/thumbs/helen-peters-helen-peters-a-piglet-called.jpg)