Published by IWM, Lambeth Road, London SE1 6HZ

iwm.org.uk

The Trustees of the Imperial War Museum, 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder and publisher.

ISBN 978-1-904897-31-6

eISBN 978-1-904897-31-6

Mobi ISBN 978-1-904897-31-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Designed by Adrian Hunt

All images IWM unless otherwise stated. Every effort has been made to contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be glad to make good in future editions any error or omission brought to their attention.

courtesy of Piers Mayfield

PREVIOUS PAGE : Guy Mayfield (right), with Peter Watson (left) and 19 Squadrons adjutant H Nicholls

FRONT COVER : (composite), IWM CH 1366 (detail, this image has been artificially coloured), IWM CH 6381 (detail), IWM CH 7688 (detail)

BACK COVER : Courtesy of Piers Mayfield

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Foreword

PIERS MAYFIELD

M Y FATHER wrote a lot. In the 1930s he worked at the Guardian , not the daily newspaper, which in those days was the Manchester Guardian , but one associated with the Church of England. This likely made it relatively easy for him to get into the habit of keeping a diary about what he was doing at Duxford. The first two entries, those for 12 December 1939 and 21 January 1940, suggest someone who was used to writing about the world around him, a skill which had played a big part in his life for several years. At times during the Battle of Britain and later, this may have helped him to feel that the world had not gone completely mad.

Im not aware that he kept a diary earlier in his life, and he certainly did not do so after the war when he was so busy with other writings. Apart from his administrative work as the Archdeacon of Hastings and the regular production of sermons, between 1958 and 1966 he published three books. For recreation he took to oil painting. Wherever we lived he would occupy a big room, one half of which was full of what he needed for writing and the other with an easel, together with all the mess which oil painters seem to need and with a radio on which he listened to Radio Luxembourg while he daubed.

In 1964 he began typing up the diary which hed kept at Duxford in 1940 and 1941, handwritten in blue RAF-issue notebooks, of which I have some of the originals. He wanted to leave a legible version of this for posterity and, as he was probably aware that his handwriting, although big, bold and usually black, could sometimes be a bit of a scrawl which was difficult to read, he typed the records up with a view to sending it off to the Imperial War Museum. Understandably, as he was picking out the letters, memories and reflections occurred to him afterthoughts which he hand-wrote in the margin of the typed copy, making a bit of a mess of what he was trying to render beautiful.

When I was small I loved the stories Guy told at mealtimes; naturally, as I grew older, I wondered how much of them was fantasy and how much reality, proportions which only he knew. Perhaps he hoped to produce something which gave more space for his storytelling when he retired. His additions gave the impression that, if he had had the time, he might have liked to write a memoir of his experiences at Duxford. Unfortunately, in his last years as Archdeacon he was not well and he died at the age of seventy-one.

Before he died he asked Thelma, my mother, if she would type a copy of what hed got together and see if the Imperial War Museum was interested. She said she would, although she hated thinking about the war and never spoke about it. Born in 1908, she was the daughter of an Engineer Captain in the Royal Navy, Malcolm Johnson; so, during the First World War, she will have been old enough to be bothered by what her father was having to do and what might happen to him. She spent the Second World War at Linton, within ten miles of Duxford, with my elder brother Robert, born in August 1940 at the height of the Battle of Britain and, from September 1942, me the pair of us providing her with too much opportunity to worry about the consequences if the war was lost.

By 1945, having spent at least nine years of her life dreading what might happen to her nearest and dearest, she wanted nothing more to do with war. Typing up the Duxford diary would also have been particularly painful because she knew a number of the pilots whose lives and deaths Guy records, so she asked me if I would carry out his wishes.

As I sat typing, I thought of the ashtray before him on the desk at which he worked. The ashtray, I long ago decided, must have come from Duxford. Ideal for a pipe-smoker like Guy, it was metal, heavy, round and a good nine inches across, with grooves around the edge upon which pipes could be rested and with plenty of space in the centre for ash. It looked as if it had originally been part of the engine of a Spitfire, which some thoughtful RAF engineer had mounted on wood so that it would not scratch the top of the padres table while he was writing his diary and puffing away as he did so. I dont know for sure because, like Thelma, Guy never talked about the war. Like the war, the ashtray was simply there, never to be discussed a silence which made discovering what happened to him at Duxford so moving.

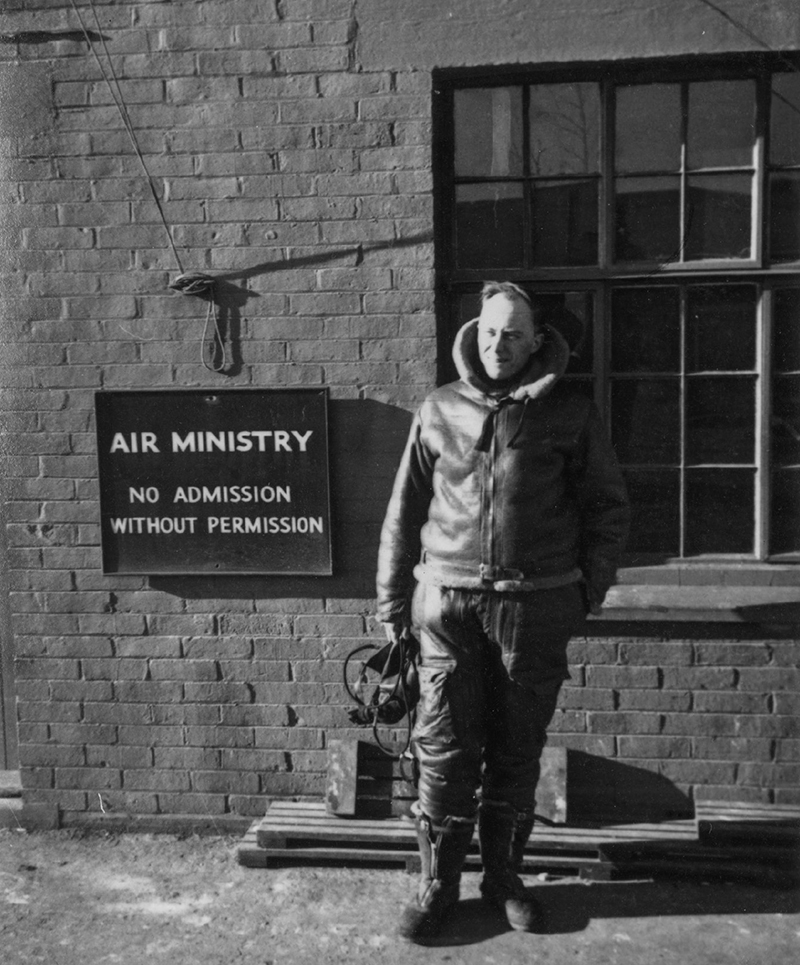

Guy Mayfield outside No. 19 Squadrons hangar, RAF Duxford. Today this building contains an exhibition about the Battle of Britain, but in 1940 it was one of the many locations Guy visited to talk to the airmen as they worked.

Introduction

CARL WARNER

G UY MAYFIELD , so lovingly described by Piers in his foreword, arrived at RAF Duxford on 2 February 1940. This placed him at the centre of a community of men and women who were about to take part in the greatest defensive air battle ever fought. In the pages of his diary we find one of the finest accounts of a fighter station at war. It is full of insight into the mind of a man who made an enormous, unsung contribution to victory, and into those of others on the station whose mental, physical and spiritual well-being he cared about so deeply.

By 1940 Duxford had already been operational for over twenty years, and was home to many fighter squadrons and test units. Guy most often references Nos. 19 and 66, who were both already there when he arrived, but they were soon joined by others, including several units that would form part of the famous Duxford Wing. Its aircraft and men were detached to operate over the North Sea and over the Channel, notably during the evacuation of Dunkirk. Then, in June 1940, the daily grind of the Battle of Britain-proper took over. Once the Battle ended, RAF Fighter Command went on the attack, launching sweeps over northern France. Duxfords pilots were involved, too, and at great cost, as the 1941 pages of the diary reveal.

IN THE

IN THE