Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Jan MacKell Collins

All rights reserved

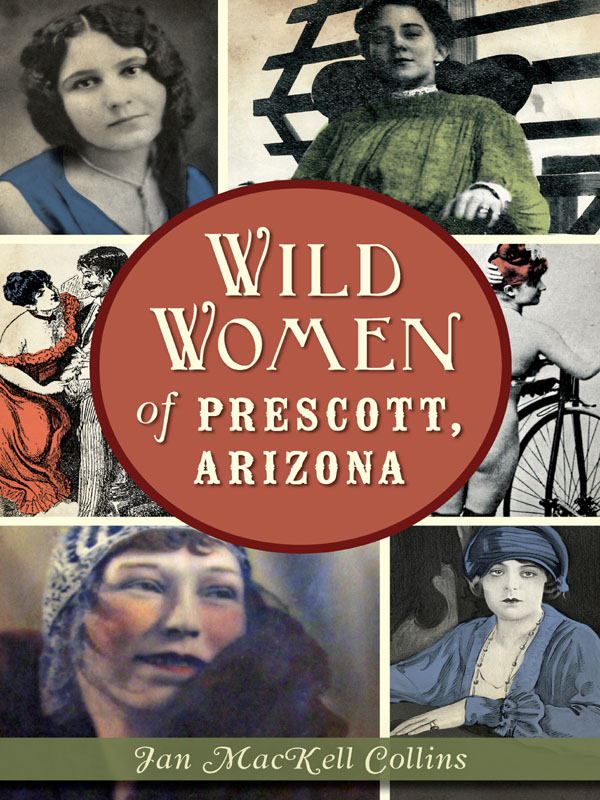

Front cover images, clockwise from top left: courtesy Gabriell Wiley estate; courtesy Tombstone Museum; courtesy Jan MacKell Collins; courtesy Jan MacKell Collins; courtesy Gabriell Wiley estate; courtesy Jan MacKell Collins.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.354.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014959947

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.863.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A number of people have worked tirelessly with me to make sure this book is the best it can be. At the forefront is Christen Thompson, my editor at The History Press, whose patience, professionalism and thoroughness have truly been a gift. Another thanks goes to Jaime Muehl, who gave me additional insight during the editing process. I would also like to thank Shelly Dudley, the lovely proprietress of Guidon Books in Scottsdale, Arizona, for introducing me to The History Press and its wonderful line of history books.

My research would not have been so complete without the help of John Brusco and John and Mary Jo Murray, who shared their information and stories about Gabe Dollie Wiley. The same goes for Tim Wellesley, who has conversed with me for years about Eliza Jane Crumleys family in Colorado, Arizona and Nevada. Prescott historians Parker Anderson, Brad Courtney, Ken Edwards, Elisabeth Ruffner, Patricia Ireland Smith, the staff at Sharlot Hall Museum Library & Archives and librarian Scott Anderson were all of immense help. I also truly appreciate the quick assistance of Laura Palma-Blandford, archivist at the Arizona State Library. Wyatt and Terry Earp and their webmaster, Dale Schmidt, have been helpful on this and so many other projects. And thank you to Bob Boze Bell and Meghan Saar at True West magazine for publishing my ongoing tales of wanton women.

I would not have had such a great inventory of images to choose from were it not for the four generations of my family who left behind hundreds of photos for me and future family members to enjoy. Also, a big thank-you goes to Professor Jay Moynahan, one of my biggest supporters, who always has one more picture for me to use. Miss Lydia Gray of California was also of immense help, as was Al Bossence of the Bayfield Bunch in Congress.

My gratitude would not be complete without thanking my beautiful husband and best friend, Corey, for putting up with me and letting me write in my pajamas all day.

INTRODUCTION

As one of the last states to enter the Union, Arizona remained a raw, rather uncivilized territory between 1863 and 1912. The untamed land lent itself to explorers, miners, ranchers, farmers and others who saw an opportunity to prosper. The growing population also included its share of shady ladies, a staple of the economy in nearly every western town. These wanton women prided themselves in being independent, hardy individuals who werent afraid to pack their petticoats across rough, barren terrain and set up shop. Their stories range from mild to wild, with plenty of colorful anecdotes in between.

Who were these daring damsels who defied social norms to ply their trade in frontier Arizona? The 1860 United States census, taken just three years before Arizona Territory was formed, listed a number of women who were living in what was then New Mexico Territory. At the time, New Mexico Territory was quite large. The population, which spanned across todays Arizona, New Mexico, a portion of Colorado and part of Nevada, included mostly Mexican women who were locally born.

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Organic Act that divided Arizona and New Mexico Territories with a northsouth border that is still in place today. The first Arizona territorial census was conducted the following year, revealing a population numbering over 4,500 people. Almost 1,100 of them were female adults and children.

Arizonas military forts, mining camps, whistle-stops and cities grew at an amazing rate. Soldiers of the early frontier forts served as ample clientele for prostitutes during Arizona Territorys formative years. Later, as mining camps grew into towns and towns bloomed into cities, a bevy of soiled doves flocked into these places and set up more permanent bordellos. In time, nearly every town included working girls who conducted business in anything from tents, to tiny one- or two-room adobe or stick-built cribs, to rooms above saloons, to posh parlor houses. Prescott, one of the earliest, wildest and fastest-growing towns in the territory, was no exception.

The census records of the 1800s are among the best resources used to identify prostitutes, but even these failed to identify every known working girl in Prescott. By 1870, the women of the town numbered a mere 108 versus 560 men. The census reveals little else about the ladies, including their marital statuses, unless they were married within that year. In most cases, the occupations of women who worked in the prostitution industry were discreetly left blank. Because the occupations of women who were unemployed or working as housewives were also unidentified in several instances, the true number of women working as prostitutes will never be known.

Not until the 1880 census were morebut not allwomen of the underworld in Prescott blatantly identified as prostitutes, sporting and fancy women, mistresses and madams. The smart prostitute revealed very little about herself and took great pains to disguise her real identity, where she came from and how she made her living. Such details, however, might be revealed in her absence by a roommate, her madam, a nearby business owner or even the census taker, who knew the occupants of the red-light district but was too embarrassed to knock on the doors there. So while girls such as Elizabeth Arbuckle were listed as prostitutes in Prescott during the 1880 census, other womensuch as madam Ann Hamiltonwere listed only as keeping house and by other indiscernible occupations.

Census records also revealed changes in the way the West viewed the prostitution industry over the next twenty years. Though the 1890 census burned up in a fire, it was obvious by 1900 that civilization had started its inevitable creep into Arizona Territory. Wives, families, churches and temperance unions were part of the growing groups in the West. Wayward ladies were forced to tone down their job descriptions to some extent. While blatant racism encouraged identifying Japanese and Chinese prostitutes as such, the Anglo women living next to them or in identified red-light districts claimed to be working as seamstresses, laundresses, milliners and other demure careers that kept them out of the spotlight as working girls.