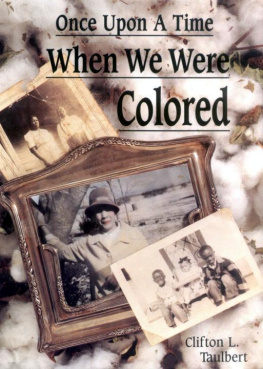

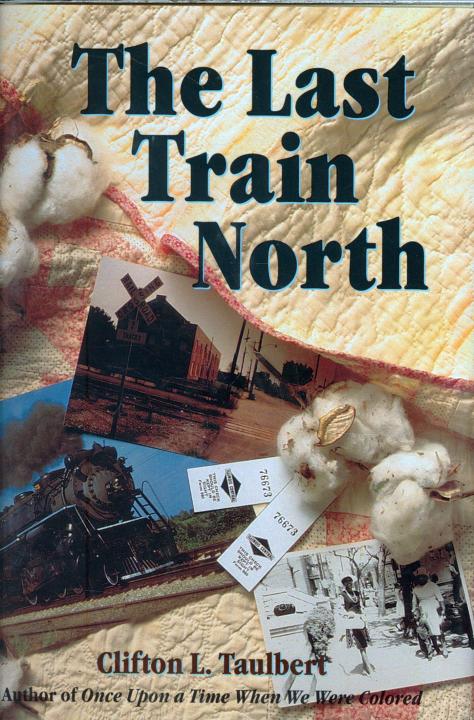

... an important, moving work." ANTHONY 0. EDDIONDS, Library Journal

"...A bittersweet story about love, community and familyand the difference they made in the life of one young man." ROSEMARY L. BRAY, The New York Times Book Review

"It depicts an era with a stalwart intimacy that mainstream history books fail to provide." DEBRA TOWNSEND, San Bernardino Precinct Reporter

"Above all there emerges from his book warmth and joy, gratitude and affirmation ..."JOHN KOCH, The Boston Globe

"A heartfelt testament to a beleaguered people who maintained dignity and created a viable, caring community ..." Kirkus Reviews

"Well written with good descriptions, it is a gem of a book." BARBARA WEATHERS, School Library Journal

"A ... highly readable ... tribute to his childhood heroes: a handful of mostly unschooled residents of rural Glen Allen who lifted his sights, made him believe he was special and pointed him toward success ..." WILLIAM RASPBERRY, The Washington Post

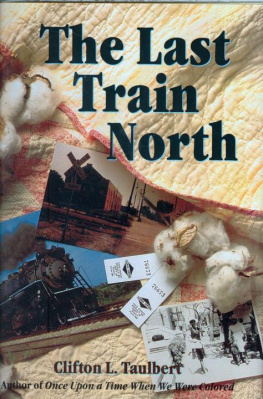

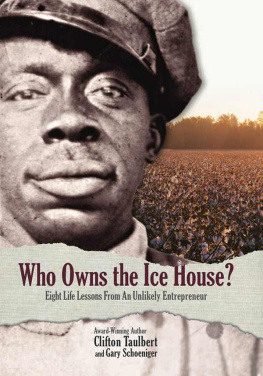

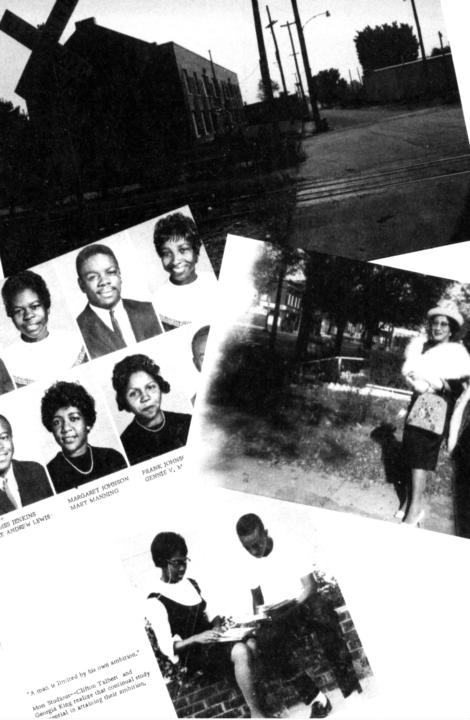

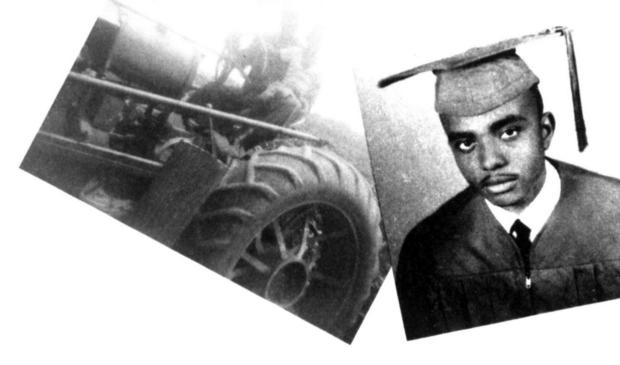

Clifton L. Taulbert, an internationally renowned speaker, is the author of the acclaimed memoirs Once Upon a Time When We Were Colored, the basis for the critically acclaimed feature film, the Pulitzer nominee The Last Train North, and Watching Our Crops Come In. His most recent book, Eight Habits of the Heart, is available from Penguin. Mr. Taulbert was the winner of the 27th annual NAACP Image Award for Literature. He was also one of the first African American writers to win the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Award for Nonfiction and was named one of America's outstanding black entrepreneurs by Time magazine. A sought-after lecturer and workshop leader on communitybuilding, Mr. Taulbert lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, with his wife and son.

Clifton L. Taulbert

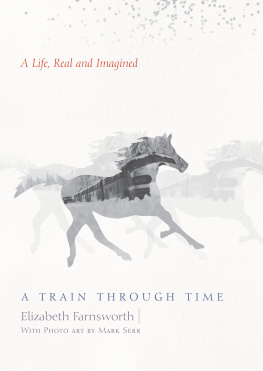

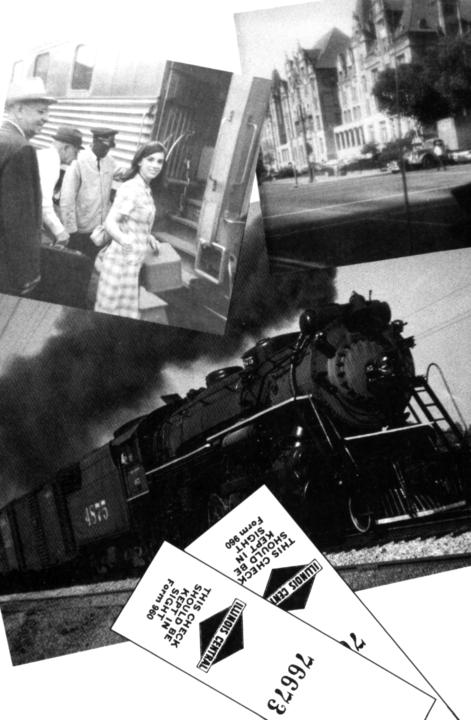

The Last Train North is the cultural diary of a seventeen-year-old African-American, a native of the Mississippi Delta, who went north during the early 1960s. He was among the last of the migrant dreamers and he went to experience the reality of the dreams he had held all his young life, dreams sparked by the summer visitors from up north, where opportunity abounded and one could sit at the front of the bus. They told of a life of integrated wonder just north of the Mason-Dixon line...

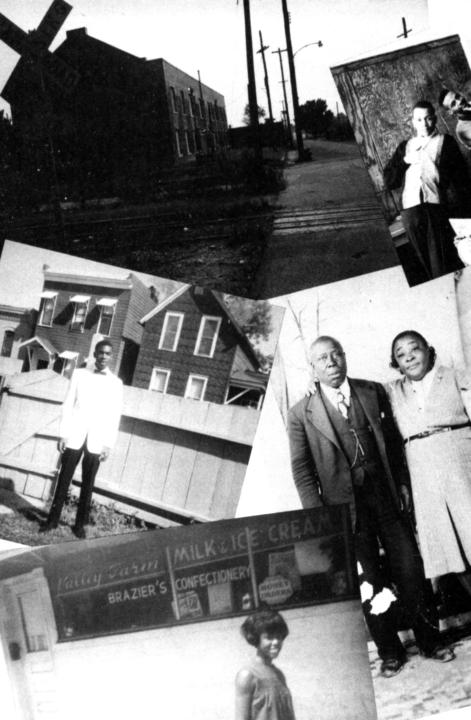

The story is dedicated to the significant folks in many of our lives, the parents, grandparents, greatgrandparents, aunts, uncles, and all the cousins of the community, who not only packed our lunches of fried chicken and pound cake and placed us in the protective care of the "colored porters," but who also invested their dreams in our generation.

The Last Train North is not the story of the great migration of African-Americans out of the rural South to the industrialized North. That happened before my time. Our northern relatives had been a part of it, and when they returned to visit us in Glen Allan, Mississippi, they told tales of glory which shaped the character of our dreams. They made those northern cities places of wonder and excitement. This is the story of the last of us who dared to dream about a fully integrated environment and staked our future on the tales told over the years by our annual summer visitors.

The Last Train North begins at the end of an era. The passenger train stopped serving the Mississippi mid-Delta in 1963, a few months after it had carried me north to seek my fortune. When I got to St. Louis the social revolution of the sixties revealed a North ofunfulfilled dreams. It wasn't the ideal society of whites and blacks living harmoniously together as had been promised to me by my Aunt Georgia when I was a child.

Aunt Georgia, and other relatives visiting us from up North told us tales of a land of opportunity beyond the segregated South. While standing, hoe in hand, on those long cotton field rows under the spacious Southern skies, my imagination knew no bounds. Whatever I wasn't told, I dreamed. Not deterred by the hot muggy Southern temperatures, I would pick and chop cotton while dreaming of the airconditioned North. Even the black shiny crows that flew aimlessly overhead seemed to agree with me that the good jobs were up North.

I could hardly wait to go North, and I knew it would be the train, the "high class" mode of transportation, that would make it all reality. Ignoring the sounds of the cotton fields, I spent my days mentally alone, riding the train. That train seemed to me like a grand uncle with a huge cigar, coming to take me North.

But this grand uncle was a neutral party, never letting on that the North of yesteryear was changing. The train just welcomed me aboard and took me to St. Louis, to face the reality of life by myself.

It was an exciting, yet a sad day, when I actually did board the Illinois Central in Greenville, Mississippi, alone and afraid, leaving my family, friends, and community behind. This is the story about what I found there, when I took my last train North, across the Mason-Dixon line.

I have many people to thank for their assistance in the completion of this cultural biography, among them: Jim and Carolyn Hefley and Stephanie Strother of Tulsa; David FspinozaofMemphis; LorettaGuyton Wilson, OscarGuyton, Sr., Oscar Guyton, Jr., Dora Brazier, and Arlander Ryan of St. Louis; and my family, Barbara, Marshall, and Anne Kathryn Taulbert; and the editorial department of Council Oak Books, headed by Dr. Sally Dennison.

C. L..i T.

MARCH, 1992