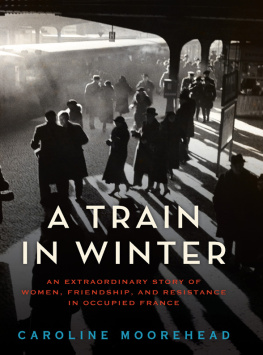

Caroline Moorehead - Train in Winter

Here you can read online Caroline Moorehead - Train in Winter full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Chatto & Windus; First Edition edition, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Train in Winter

- Author:

- Publisher:Chatto & Windus; First Edition edition

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Train in Winter: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Train in Winter" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Train in Winter — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Train in Winter" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A

TRAIN

IN

WINTER

An Extraordinary Story of

Women, Friendship, and Resistance

in Occupied France

Caroline Moorehead

To Leo

Contents

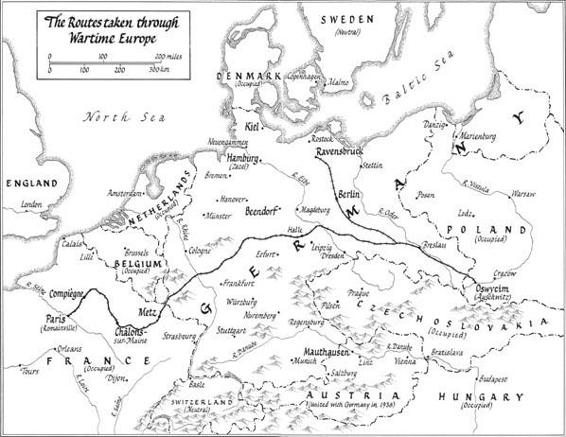

On 5 January 1942, a French police inspector named Rondeaux, stationed in the 10th arrondissement of Paris, caught sight of a man he believed to be a wanted member of the French Resistance. Andr Pican was a teacher, and he was indeed the head of the Front National of the Resistance in the Seine-Infrieure; there was a price of 30,000 francs on his head for the derailing of a train carrying requisitioned goods and war materiel to Germany.

Rondeauxs superior, a zealous anti-communist Frenchman and active collaborator of the Gestapo called Lucien Rotte, thought that Pican might lead them to other members of the Resistance. Eleven inspectors were detailed to follow, but not to arrest, him.

Over the next two weeks, they searched the streets of Paris in vain. Then, on 21 January, an inspector carrying out a surveillance of the Caf du Rond near the Porte dOrlans thought he saw a man answering to Picans description. He followed him and watched as he stopped to talk to a thickset man in his thirties, with a bony face and a large moustache. Rottes men stayed close. On 11 February, Pican was seen standing outside a shop window, then, at 15.50 entering a shop in the company of a woman 2830 years of age, 1.70m high, slender, with brown hair curling at the ends; she was wearing a Prussian blue coat, with a black belt and light grey woollen stockings, sans lgance . The policeman, not knowing who she was, christened her Femme Buisson-St-Louis after a nearby mtro station; Pican became Buisson. After watching a film in Le Palais des Glaces cinema, Pican and Femme Buisson were seen to buy biscuits and oysters before parting on the rue Saint-Maur.

In the following days, Pican met Motte Piquet, Porte Souleau and Femme No. 1 de Balard. Not knowing who they were, the police officers gave them the names of the places where they were first seen.

On 12 February, Femme Buisson was seen to enter the Caf au Balcon, where she was handed a small suitcase by Merilmontant a short woman in her mid-thirties, c. 1.55m, dark brown hair in a net, black coat, chic fauve leather bag, red belt. By now, Pican had also met and exchanged packets with Femme Brunet St Lazare (34, 1.60m, very dark, pointed nose, beige coat, hood lined in a patterned red, yellow and green material), and with Femme Claude Tillier (1.65m, 33, dark, somewhat corpulent, bulky cardigan and woollen socks). Femme Vincennes (1.60m, 32, fair hair, glasses, brown sheepskin fur coat, beige wool stockings) was seen talking to Femme Jenna and Femme Dorian. One of the French police officers, Inspector Deprez, was particularly meticulous in his descriptions of the women he followed, noting on the buff rectangular report cards which each inspector filled out every evening that Femme Rpublique had a small red mark on her right nostril and that her grey dress was made of angora wool.

By the middle of February, Pican and his contacts had become visibly nervous, constantly looking over their shoulders to see if they were being followed. Rotte began to fear that they might be planning to flee. The police inspectors themselves had also become uneasy, for by the spring of 1942 Paris was full of posters put up by the Resistance saying that the French police were no better than the German Gestapo, and should be shot in legitimate self-defence. On 14 February, Pican and Femme Brunet were seen buying tickets at the Gare Montparnasse for a train the following morning to Le Mans, and then arranging for three large suitcases to travel with them in the goods wagon. Rotte decided that the moment had come to move. At three oclock on the morning of 15 February, sixty police inspectors set out across Paris to make their arrests.

Over the next forty-eight hours they banged on doors, forced their way into houses, shops, offices and storerooms, searched cellars and attics, pigsties and garden sheds, larders and cupboards. They came away with notebooks, addresses, false IDs, explosives, revolvers, tracts, expertly forged ration books and birth certificates, typewriters, blueprints for attacks on trains and dozens of torn postcards, train timetables and tickets, the missing halves destined to act as passwords when matched with those held by people whose names were in the notebooks. When Pican was picked up, he tried to swallow a piece of paper with a list of names; in his shoes were found addresses, an anti-German flyer and 5,000 francs. Others, when confronted by Rottes men, shouted for help, struggled, and tried to run off; two women bit the inspectors.

As the days passed, each arrest led to others. The police picked up journalists and university lecturers, farmers and shopkeepers, concierges and electricians, chemists and postmen and teachers and secretaries. From Paris, the net widened, to take in Cherbourg, Tours, Nantes, Evreux, Saintes, Poitiers, Ruffec and Angoulme. Rottes inspectors pulled in Picans wife, Germaine, also a teacher and the mother of two small daughters; she was the liaison officer for the Communist Party in Rouen. They arrested Georges Politzer, a distinguished Hungarian philosopher who taught at the Sorbonne, and his wife Ma, Vincennes, a strikingly pretty midwife, who had dyed her blond hair black as a disguise for her work as courier and typist for the Underground, and not long afterwards, Charlotte Delbo, assistant to the well-known actor-manager Louis Jouvet.

Then there was Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier, Femme Tricanet, niece of the creator of the Babar stories and contributor to the clandestine edition of LHumanit , and Danielle Casanova, Femme No. 1 de Balard, a dental surgeon from Corsica, a robust, forceful woman in her thirties, with bushy black eyebrows and a strong chin. Ma, Marie-Claude and Danielle were old friends.

When taken to Pariss central Prefecture and questioned, some of those arrested refused to speak, others were defiant, others scornful. They told their interrogators that they had no interest in politics, that they knew nothing about the Resistance, that they had been given packets and parcels by total strangers. Husbands said that they had no idea what their wives did all day, mothers that they had not seen their sons in months.

Day after day, Rotte and his men questioned the prisoners, brought them together in ones and twos, wrote their reports and then set out to arrest others. What they did not put down on paper was that the little they were able to discover was often the result of torture, of slapping around, punching, kicking, beating about the head and ears, and threats to families, particularly children. The detainees should be treated, read one note written in the margin of a report, avec gard , with consideration. The words were followed by a series of exclamation marks. Torture had become a joke.

When, towards the end of March, what was now known as laffaire Pican was closed down, Rotte announced that the French police had dealt a decisive blow to the Resistance. Their haul included three million anti-German and anti-Vichy tracts, three tons of paper, two typewriters, eight roneo machines, 1,000 stencils, 100 kilos of ink and 300,000 francs. One hundred and thirteen people were in detention, thirty-five of them women. The youngest of these was a 16-year-old schoolgirl called Rosa Floch, who was picked up as she was writing Vive les Anglais! on the walls of her lyce . The eldest was a 44-year-old farmers wife, Madeleine Normand, who told the police that the 39,500 francs in her handbag were there because she had recently sold a horse.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Train in Winter»

Look at similar books to Train in Winter. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Train in Winter and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Moorehead - Coopers Creek to LangTang II. [With plates, including portraits.]](/uploads/posts/book/221288/thumbs/moorehead-coopers-creek-to-langtang-ii-with.jpg)