Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

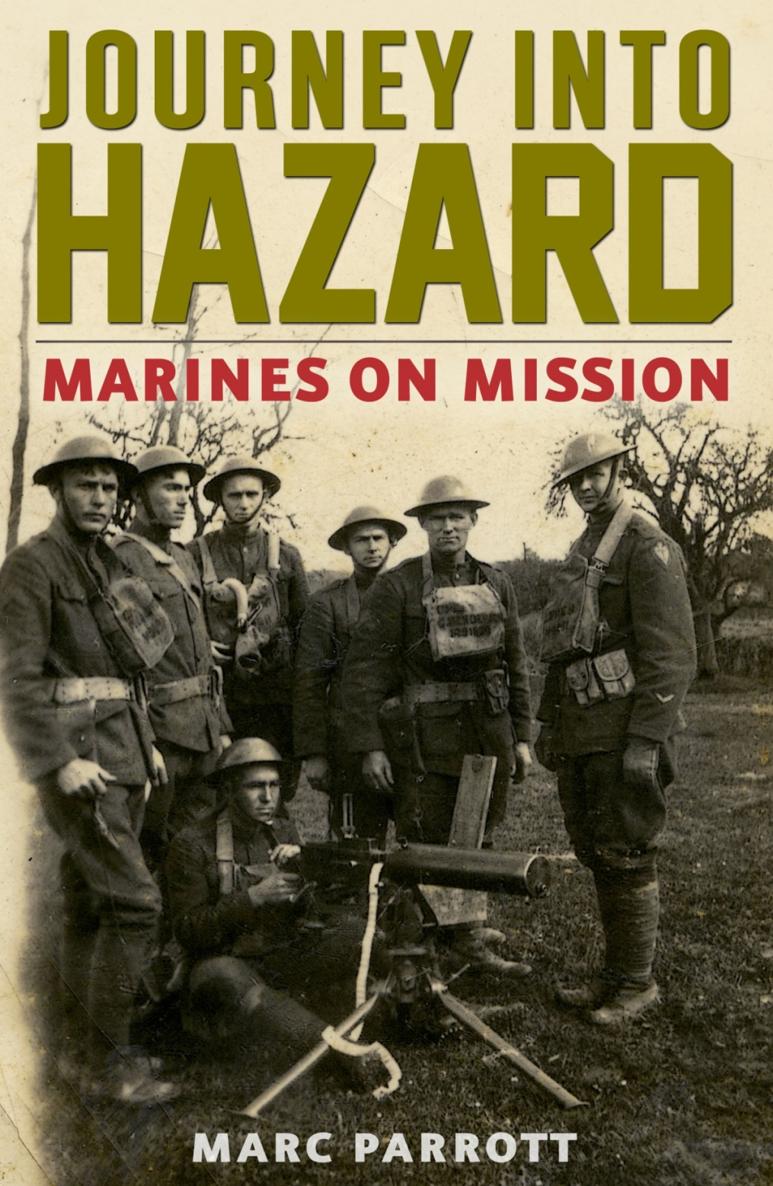

JOURNEY INTO HAZARD

Marines on Mission, 1804-1945

By

MARC PARROTT

Introduction by General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., USMC (Ret.)

Journey into Hazard: Marines on Mission, 1804-1945 was originally published in 1962 as Hazard: Marines on Mission by Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York.

* * *

To J.C.P.

APOLOGIA: In the Form of an Authors Preface

Any book making a pretense to decency has to be its own excuse, but it will perhaps help the reader if he understands that this one represents the more or less chance coupling of two ideas.

For a long time now I have thought about doing a book on men on journeys into hazard, because of the several themes this, possibly, requires the least apologetics. The greatest of all treatments of the topic, Homers, starts from the commonplace, basic but still gutsy, journey = life. It must have been well established in the human mind long before Odysseus first appears in comfortable durance at Calypsos version of a villa in Antibes.

What was contemplated originally was a book of the more uncommon American travels. There seemed to be room for such a work in an age when, for instance, a younger friend of mine, a straight A history graduate from a leading Western university, had never even heard the phrase The Message to Garcia, and schoolboys no longer know anything about Sheridan twenty miles away, or Boones escape from the Shawnees. A prospectus of such a book was submitted to an editor; it happened to contain the incidents worked up here into the chapters on Sergeants Hanneken and Diamond, and the final form the book assumed stems from his suggestion that unity was to be obtained by narrowing, so far as possible, my cast to Marines. This triggered some old-school-tie loyalties and memories of brief but interesting years when this writer, though nearly qualifying for the Order of the N.L.D., or Never Left Desk, traveled with the club from Parris Island to Peking by way of Peleliu, a tour that cannot be laid on, today, by the most resourceful travel agent.

There are both meretricious and valid approaches to a book on Marines, and writers have produced examples of both. There is, for instance, what might be termed the battle, bar, and bedroom book about the USMC, and bad as it generally is, it goes back to a reality, the recruiting-poster myth, which a sociologist might call a useful myth in that it probably enlists X number of boobs and suckers per year, some of whom turn out well. This literary convention, too, actually produced one good work, the play What Price Glory? written by Maxwell Anderson and Laurence Stallings, the latter an ex-Marine who got some of the marvelous snow-jobs into his dialogueand the quality, too, of the myth underlying the snow-jobs, to which Sergeant Quirt finds himself responding as he leaves the hard-won cantinire and follows Flagg offstage with the imperishable curtain line: Hey, Captain! Wait for baby.

But the battle, barroom, etc., approach is not that elected here, for the astonishing and potentially disillusioning thing about Marines might as well be faced: they are the same as other people; at least, they start out that way. That old saw of athletic coaches, speaking of dreaded opponents to their squads, is operative here: they put their pants on one leg at a timejust like you.

Why, then, have Marines remained box office, so to speak? The bulk of the present manuscript, in its way, aims to help elucidate this problem, and in an afterword the author cites some excellent writers who may shed further light. Overwhelmingly and obviously, I myself surmise, it has been their battle record and consequent fameArmy propaganda to the contrary it is not true that all Marines are assessed for the tab charged by their advertising agency (which happens to be J. Walter Thompson; one old-line firm aids another one). The Marines best propaganda has usually been the naked event. When historically minded citizens have totaled accounts, the Belleau Woods, Wakes, Guadalcanal, and Iwos have outweighed adverse entries like the Ribbon Creek disaster, the fact that one Commandant was an alcoholic and that, like the other United States forces on that field in 1814, the Marines made reasonably good time rearward from Bladensburg, Maryland. And the good word-of-mouth has generally muffled adverse voices, even those of five or six loud ill-wishers who happened to be Presidents of the United States. In the 1930s, the great first basemanmanager of the Giants, Bill Terry, had a stock answer to reporters when a vital series was coming up: Ill lead with my ace, said he invariably. That was Carl Hubbell. So, in its altercations, large and small, the United States has treated its odd military stopper. In both World Wars there was substance to the First to Fight claim, and between big wars, after the Indian campaigns died out, Marines were virtually our only troops to fight at all.

Fascinating too, if less ponderable than the battle record, has been the hybrid, almost protean nature of the Marine, soldier and sailor, too, as Kipling called his British counterpart. For a long time his role was a symbiotic existence within the various navies of the age of sail. In battle he was a sniper. On ordinary days, commanders found it useful to have a body of men whose loyalties dependably lay aft in officers country rather than with the potentially mutinous forecastle of those dangerous times. (Bligh had no Marines on the Bounty, a mistake he corrected before he next went voyaging.) Gradually this connection with fleets has been almost lost, but more recently, United States Marines, though no others known to their historian, Robert Sherrod, took to the air, with results that may properly be called historic when at Guadalcanal the malarial and dysentery-ridden Cactus Air Force turned back the foe in Americas analogy to the Battle of Britain. Versatility has been expected of Marines. An outrageously boastful but luckily apocryphal yarn runs as follows: One day in the 1920s some bureaucrat or plantation owner in a banana republic telegraphed the Natives restless bit to the port city where there was a Marine contingent. In response, some time later, a solitary Marine got off the train at the trouble spot, whereupon the dialogue went like this:

BUREAUCRAT: I ask for help, and they send me one Marine!

MARINE: So? There wasnt but one rising, was there?

For the Marine has had the repute of a Mr. Fix-it.

And the most controversial possible cause for public interest in the Corps has been everyones fascination with elites, a word popularized by the Italian egghead sociologist Pareto and of enduring interest to bidders at yearling sales, millions of straphangers devouring the social columns, and to Professor C. Wright Mills of Columbia University, who says the United States is steered by one. (There should be no automatic bristling of hackles at the word elite: the thing exists.) Now, this reputation, too, has commonly been borne by Marines, and borne with some complacency; a highly intelligent Marine officer I once knew, not given to bragging, used to put the Corps with the Legion Etrangere and the Guards Brigade as one of three unique military organizations in the Western world.