Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Ajax Delvecki and Larry Johnson

All rights reserved

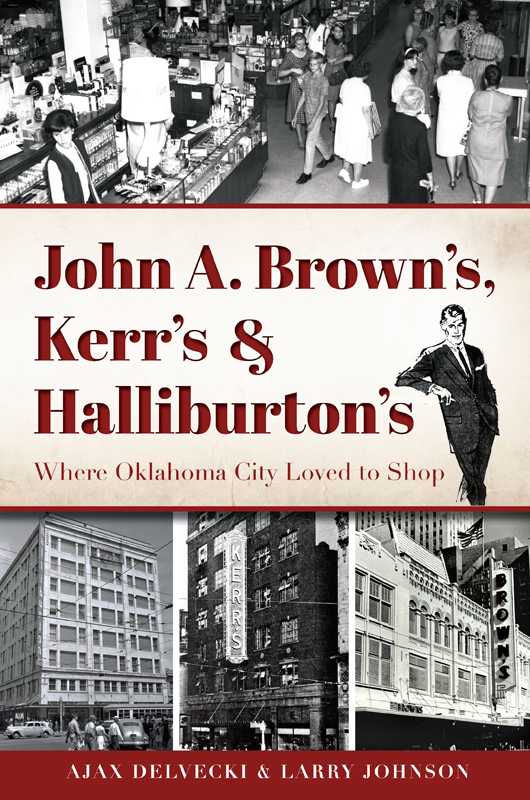

Front cover: John A. Brown Co., Downtown, 1971. Photograph by Dave Heaton; courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society, the Gateway to Oklahoma History.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.43965.846.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016937192

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.360.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Donna Douglas, 19252014 Employee of Kerrs and Halliburtons. Although she never worked at Browns, she could certainly appreciate that stores quiet philanthropy and Dellas admirable business acumen.

Introduction

Welcome, Carnivalgoers, to Oklahoma City!

Oklahoma City was born by presidential proclamation in a single day. On the morning of April 22, 1889, opportunists flooded into the Unassigned Lands for free land and a fresh crack at the pursuit of happiness. By days end, a tent city of ten thousand settlers had formed a community alongside the Santa Fe rail station.

Some of those settlers who intended on claiming a farmstead arrived in wagons loaded with just enough tools and supplies to establish a claim and probably included no more than a weeks rations. However, most of Oklahoma Citys pioneers arrived by train from Kansas or Texas, stepping off the passenger platform with a single handbag and limitless hope. For miles and miles, the land on either side of the Santa Fe railroad tracks was devoid of people, farms and crops. Everything the settlers neededfood, lumber, toolshad to be brought in by rail. Still, although the method of founding of Oklahoma City was unique at that time, the process of building a new railroad town from scratch on the open prairie was fairly well developed by 1889, and colonizing retail merchants were part of that process. As it happened, nearly every store in those first few years had originated from a store in Kansas, Texas or points farther east.

Several fortunes were made in those days. The most notable of these was that of William J. Pettee, who later earned the sobriquet Daddy of Main Street because of his large, successful hardware store and other Main Street ventures. Pettee, a young twenty-something from northeast Kansas, was dispatched to Oklahoma City from Osage City by his father, who ran a successful store there. On April 23, 1889, Pettee sold a freight car full of building materials and other basic goods directly from the railroad siding in a single day, earning enough capital to seed his hardware store and launch his real estate empire.

Thomas Meriwether Richardson was selected by his family-run lumber company to establish a foothold in the new city. The company had already created a veritable building material empire across Texas and the Southwest, and Richardson arrived a few hours after the land run with a freight car of goods and pre-printed notes with which he could issue credit. Within days, he had converted the merchandise into cash and IOUs and was able to establish not only a permanent store but also what he claimed was the first bank in Oklahoma City.

Generally, though, Oklahoma City slogged through the 1890s. In the first couple years, the city weathered a flu epidemic and a crop failure, which required federal intervention. From the initial 10,000 or so settlers, only about 4,500 remained after the first year. After that, the population leveled out at around 7,000 for most of the decade. Complicating matters, a national depression beginning in 1893 hampered economic growth in the region. Thats not to say the boosters were not busy. Led by men like Charles Gristmill Jones, Louis F. Kramer and Henry Overholser, the city was able to woo three major railroads and a half dozen smaller ones by the turn of the century. The immediate effect of these railroad-building efforts was that the city was positioned as a regional hub for warehousing and wholesaling goods. No less important was that outside investors observed that Oklahoma City had more going for it than the territorial capital, Guthrie.

Originally, the business district was confined to just a few blocks. Broadway developed along a line parallel to the Santa Fe tracks, and you could find mainly hotels, rooming houses and restaurants along a stretch from California Avenue north to Second Street. Grand Avenue (now Sheridan) was the petty kingdom of Henry Overholser, who owned a majority of the lots along the eastwest street. There were few retail stores, and you could find a number of entertainment venues like bars, gambling houses and theaters, including the ornate Overholser Opera House. Main Street was a kaleidoscope of shops and restaurants running west from Broadway to Harvey, most of them twenty-five-by fifty-foot storefronts, packed into the two-block stretch like sardines. Beyond Harvey to the west were mainly homes and rooming houses. First Street (now Park Avenue) was largely industrial because of the presence of the Choctaw and Frisco tracks. Though hard to imagine today, First Street housed grain mills, light manufacturing and plants like the Armour meatpacking facility. The south and the east sides of the original city were largely undeveloped except for the large warehouse district known as Bricktown today.

At the turn of the century, Guthrie and Oklahoma City were neck and neck in terms of population (about ten thousand each) and influence, but an uptick in the national economy tilted the balance in Oklahoma Citys favor. Businessmenincluding a budding Anton Classen, soon to be one of the most influential men in the citys historybegan an exodus from the capital to its more robust neighbor to the south. Arriving in 1900, Classen began aggressively developing the northwest part of the city, first building on the northern edge and then using the streetcar franchise he owned with John W. Shartel to expand rapidly farther north and west.

That first decade of the twentieth century saw a ferocious boom in the city. Statehood was imminent (1907), and Oklahoma City made no secret of the fact that it was gunning for Guthrie. Boosters made numerous junkets to the east, selling the city at every opportunity and announcing their intent to wrest the state capital from their poorer brethren to the north. It worked. Businessmen continued to flock to town hoping to cash in on this brash, new boomtown. Along Broadway, buildings began to rise above three stories for the first time, and on Main Street, bigger and better stores began offering more variety and greater quality merchandise as middle-class homeowners rode Mr. Classens streetcar downtown for shopping excursions.

![Waring Todd - Oklahoma City: [what the investogation missed-- and why it still matters]](/uploads/posts/book/242598/thumbs/waring-todd-oklahoma-city-what-the.jpg)

![Gumbel Andrew - Oklahoma City : [what the investogation missed-- and why it still matters]](/uploads/posts/book/98695/thumbs/gumbel-andrew-oklahoma-city-what-the.jpg)