For Mrs Elsie Walton family historian, fashion researcher and friend

CONTENTS

Thank you in general to all History Wardrobe fans who have contributed photographs, anecdotes, costume donations and good all-round enthusiasm.

Thank you in particular to the following individuals and institutions:

Dee Curran for the fabulous studio photographs www.denisecurran.com

Meridith Towne for modelling costumes and for ongoing performances with History Wardrobe www.meridithtowne.co.uk

Mrs Elsie Walton, indefatigable comrade-in-costume

Ben and Lorna Adlington, for feeding my passion for womens history and for feeding me cake when required

Mrs Melanie Towne, for knitting the fantastic khaki wool socks

Grace Evans, costume curator at Chertsey Museum www.chertseymuseum.org

Platt Hall Museum of Costume, Manchester www.manchestergalleries.org

Kay-Shuttleworth Textile Collection, Gawthorpe Hall www.nationaltrust.org.uk/gawthorpe-hall

Jo deVries and Katie Beard at The History Press for their creative enthusiasm and hard work

Kate Shaw, Agent Extraordinaire

Picture Credits

All images are from the authors personal collection, with the following exceptions:

Author photo courtesy of Eric H. Fisher A7EHF Photography

Jane Wharton Museum of London collection

Dora Thewliss postcard courtesy of Jill Liddington, author of Rebel Girls, Their Fight for the Vote (Virago Press, 2006)

Prison wardress courtesy of Margaret Bennett

Green wool suit courtesy of Meridith Towne

Nurses Steele & Stead courtesy of Vicky Warwick

Edith Appleton portrait, courtesy of Dick Robinson, Edies great nephew

Jessie Harding courtesy of Millicent Harrison

Engine cleaners at the Shilden works courtesy of Darlington Head of Steam Museum

Annie Colley images courtesy of Raymond Colley

courtesy of Maureen Marshall

Bus conductress and Annie Cragg courtesy of Normal Ellis

WRN Imperial War Museum collection

Dick, Kerrs Ladies team photo courtesy of Gail Newsham, author of A League of Their Own (Pride of Place Publishing, 1994)

Quote from Laurence Atwell p. 108 from Letters from the Front , Pen & Sword Publications

www.pen-and-sword.com

Wages, prices, values so much has changed over 100 years. There is no perfect formula for converting a price tag from 1914 to something comparable in 2014.

The National Archives (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency) suggests conversion rates for spending worth. For example, in 1915 1 was the equivalent of 43 in 2005. With this formula, a 6 shilling corset (a basic, medium-quality, long-lasting garment) would cost 12.92 in 2005 hardly representing a great outlay from a modern annual clothes budget.

The formula does help give a feeling for larger sums of money, so 1,000 raised for charity by the sale of hand-sewn articles would be about 43,000 in modern money a great achievement.

One easier way to appreciate the prices mentioned in this book is to think how much proportion of a weekly wage would this represent?

For example, the 6 s corset would be a big investment for a servant earning 10s a week. It would still be a big outlay for a munitions factory worker earning 1 (20 s ) a week, but it wouldnt make too great a dent in the 30 (600 s ) dress allowance of a middle-class Miss.

A second-hand Singer sewing machine on sale at 4 (80 s ) would, for a seamstress earning 2 shillings a day from outsourced work, take forty days work to buy if only she didnt have the expenses of rent, rates, food, sewing cotton, clothing and medical fees to eat up all her wages. An 18 fox fur set would be an impossible dream for any but the wealthiest women.

Inflation was extremely high during the war. The annual cost of womens clothing ordinarily purchased by the working class rose by a shocking 90 per cent between 1914 and 1918:

1914 price | 1918 price |

Costumes | 44 s | 80 s 3d |

Dresses | 8 s | 15 s 11 d |

Underwear | 3 s 2 d | 6 s |

Corsets | 4 s | 6 s 11 d |

Hats | 10 s 7 d | 19 s 2 d |

Stockings | 1 s 8 d | 3 s 5 d |

Aprons | 1 s 4 d | 2 s 3 d |

Boots | 11 s 6 d | 22 s 4 d |

Shoes | 9 s 6 d | 21 s 9 d |

Boot repairs | 2 s 1 d | 4 s 5 d |

(From the Working Classes Cost of Living Committee 1918 Report, HMSO) |

To help with calculations of pre-decimal money:

12 pennies ( d ) | = 1 shilling |

20 shillings ( s ) | = 1 pound |

1 guinea (gn) | = 1 pound and 1 shilling (21 shillings) |

It is 1910. The first year of a new decade. In a nice mid-terrace house Mrs Average, a nice middle-aged, middle-class woman, is getting dressed for the day.

This will take some time.

To the modern eye, Edwardian-era fashions evoke awe and admiration. Viewing photographs and fashion prints we might remark on how stylish the women look, how feminine. A closer look at the layers that make up a basic daytime ensemble gives an idea of the way in which women were physically hampered by their clothes as well as socially constrained by the need to look respectable.

Unmentionables

We begin with underwear and theres plenty of it.

Ladies who could afford high-end lingerie from fashion houses indulged in luxurious confections of silk crpe de Chine, light georgette or lace. For warmth and hygiene, wool next to the skin was recommended; for economy, flannelette. Undergarments in white cotton were by far the most common, perhaps with pretty touches of ribbon or broderie anglaise. For the first layer, there was a choice of chemise and drawers, or combinations.

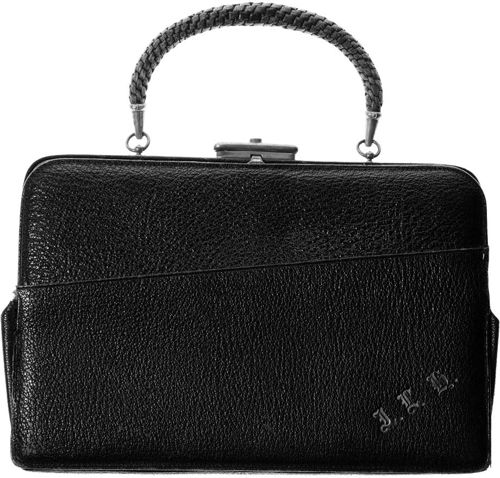

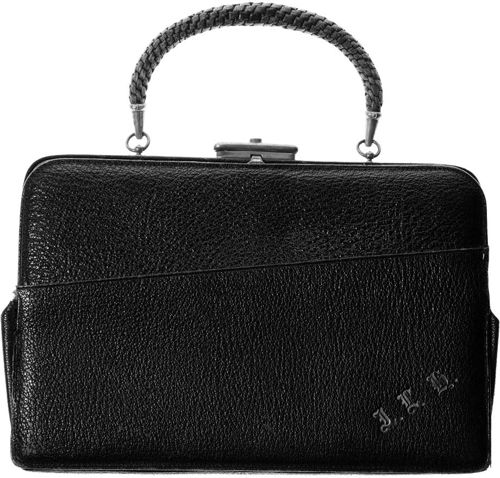

The chemise also known as a shift or a shimmy was the forerunner of todays vest. It was considered rather outmoded in the pre-war years, although for many centuries it had been obligatory wear for women, corresponding to the shirt for men. The humbler chemise was made of plain homespun linen or sturdy cotton. Fancier versions were of a light cotton lawn with lace trimmings at the throat. Shaped like a generous T-shirt reaching the knees, the main purpose of the chemise was to protect the subsequent layers of clothes and to soak up perspiration highly necessary in an age before commercial deodorants. Sturdy French seams enabled the chemise to survive repeated and vigorous washing. Inked or embroidered initials meant undies didnt get lost at the laundry.

Drawers were shaped like feminine knee breeches. They were usually split at the crotch to enable the wearer to use the toilet with the least fuss possible, although modern women who attempt this may find it a rather hit-and-miss affair, even on a fitted WC. Hovering over a chamber pot required quite a knack with fabric management, as well as strong thighs. Even more awkward to cope with was an Edwardian innovation in drawers new models stitched at the crotch. This was said to signify greater dignity for women, but surely it meant also a greater inconvenience. These drawers, whether flimsy silk affairs with embroidery and lace, or racy-coloured tango pants for flamboyant dancing, were the direct ancestors of modern knickers. They fastened with a neat button at the waist or alarmingly weak elastic.

Next page