About the Author

Lucy Adlington is a British dress historian with more than twenty years experience researching social history. Adlington runs History Wardrobe, a company which presents costume-in-context talks across the UK. Her non-fiction publications include: Womens Lives and Clothes in WWII: Ready for Action and Stitches in Time the Story of the Clothes we Wear.

Lucy Adlington lives on a farm in Yorkshire.

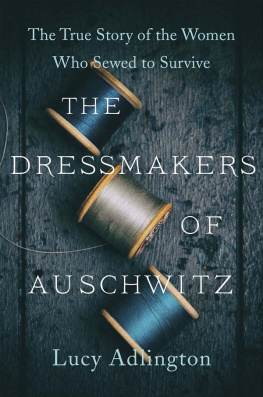

THE DRESSMAKERS OF AUSCHWITZ

The True Story of the Women Who Sewed to Survive

Lucy Adlington

www.hodder.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Copyright Lucy Adlington 2021

The right of Lucy Adlington to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Cover image: Lee Avison/Trevillon Images

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

eBook ISBN 9781529311990

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.hodder.co.uk

Dedicated to the dressmakers and their families

Contents

How to Use this eBook

Look out for linked text (which is in blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between notes and main text.

You can double tap images to increase their size. To return to the original view, just tap the cross in the top left-hand corner of the screen.

Introduction

How could you believe it?

These are some of Mrs Kohts first words to me, once I have been welcomed into her home and overwhelmed by supportive relatives. Here she is, a small, bright woman dressed in smart slacks, blouse and bead necklace. Her hair is short and white; her lipstick is rose pink. She is the reason I have flown around the world, from the north of England to a modest house in the hills, not far from the great city of San Francisco, California.

We shake hands. At that moment history becomes real life, not just the archives, book stacks, fashion drawings and fluid fabrics that are my usual historical sources for writing and presenting. I am meeting a woman who has survived a time and place now synonymous with horror.

Mrs Koht sits at a lace-covered table, offering home-made apple strudel. During our meetings she has a backdrop of scholarly books, mingled with flower bouquets, pretty embroideries, family photos and colourful ceramics. We ease into the first interview by browsing the 1940s dressmaking magazines that I brought to show her, then examining a stylish, red wartime dress from my own collection of vintage clothes.

Good quality work, she comments, running her fingers over the dresss embellishments. Very elegant.

I marvel at how clothes can connect us across continents and generations. Underlying the shared appreciation of cut, style and skill is a far more significant fact: decades before, Mrs Koht was handling fabrics and garments in a very different context. She is the last surviving dressmaker from a fashion salon established at Auschwitz concentration camp.

A fashion salon in Auschwitz? The very idea is a hideous anomaly. I was staggered when I first saw mention of the Upper Tailoring Studio, as it was called, while reading about links between Hitlers Third Reich and the fashion trade, in preparation for writing a book about global textiles in the war years. It is clear that the Nazis understood the power of clothes as performance, demonstrated by their adoption of iconic uniforms at monumental public rallies. Uniforms are a classic example of using clothing to reinforce group pride and identity. Nazi economic and racial policies aimed to profit from the clothing industry, using the proceeds of plunder to help fund military hostilities.

Elite Nazi women also valued clothing. Magda Goebbels,

And yet, a fashion salon in Auschwitz? Such a workshop encapsulated values at the core of the Third Reich: qualities of privilege and indulgence, bound up with plunder, degradation and mass murder.

The Auschwitz dressmaking workshop was established by none other than Hedwig Hss, the camp commandants wife. As if this conjunction of fashion salon with extermination complex was not grotesque enough, the identity of the workers themselves makes for the ultimate impact: the majority of the seamstresses in the salon were Jewish, dispossessed and deported by the Nazis, ultimately destined for annihilation as part of the Final Solution. They were joined by non-Jewish communists from Occupied France, who were fated for incarceration and eradication because of their resistance to the Nazis.

This group of resilient, enslaved women designed, cut, stitched and embellished for Frau Hss and other SS wives, creating beautiful garments for the very people who despised them as subversives and subhuman; the wives of men actively committed to destroying all Jews and all political enemies of the Nazi regime. For the dressmakers in the Auschwitz salon, sewing was a defence against gas chambers and ovens.

The seamstresses defied Nazi attempts to dehumanise and degrade them by forming the most incredible bonds of friendship and loyalty. As needles were threaded and sewing machines whirred, they made plans for resistance, and even escape. This book is their history. It is not a novelisation. The intimate scenes and conversations described are based entirely on testimonies, documents, material evidence and memories recounted to family members or to me directly, backed up by extensive reading and archival exploration.

Having once learned that such a fashion salon existed, I began deeper research, with only some basic information and an incomplete list of names Irene, Rene, Bracha, Katka, Hunya, Mimi, Manci, Marta, Olga, Alida, Marilou, Lulu, Baba, Boriskha . I had almost given up hope of finding out more, let alone learning full biographies about the dressmakers, when the Young Adult novel I wrote set in a fictional version of the workshop titled The Red Ribbon caught the attention of families in Europe, Israel and North America. Then the first emails arrived:

My aunt was a dressmaker in Auschwitz

My mother was a dressmaker in Auschwitz

My grandmother ran the dressmaking workshop in Auschwitz

For the first time I had contacts with the families of the original dressmakers. It was both shocking and inspirational for me to begin discovering stories of their lives and fates.

Remarkably, one of the group of dressmakers is still alive and well and ready to talk a unique eyewitness to a place that exemplifies the hideous contradictions and cruelties of the Nazi regime. Mrs Koht, 98 years old at the time of our meeting, spills out stories even before I can ask questions. Her memories range from being showered with nuts and candy as a child during the Jewish Feast of the Tabernacle, to watching a school friend in Auschwitz have her neck broken by an SS man with a shovel, simply for speaking while working.

She shows me pictures of herself before the war, as a teenager in a nice, knitted sweater holding a magnolia, then one from several years after the war, wearing a stylish coat modelled along the lines of Christian Diors famous New Look. To see these photographs, you would never guess the reality of her life during the years in-between.