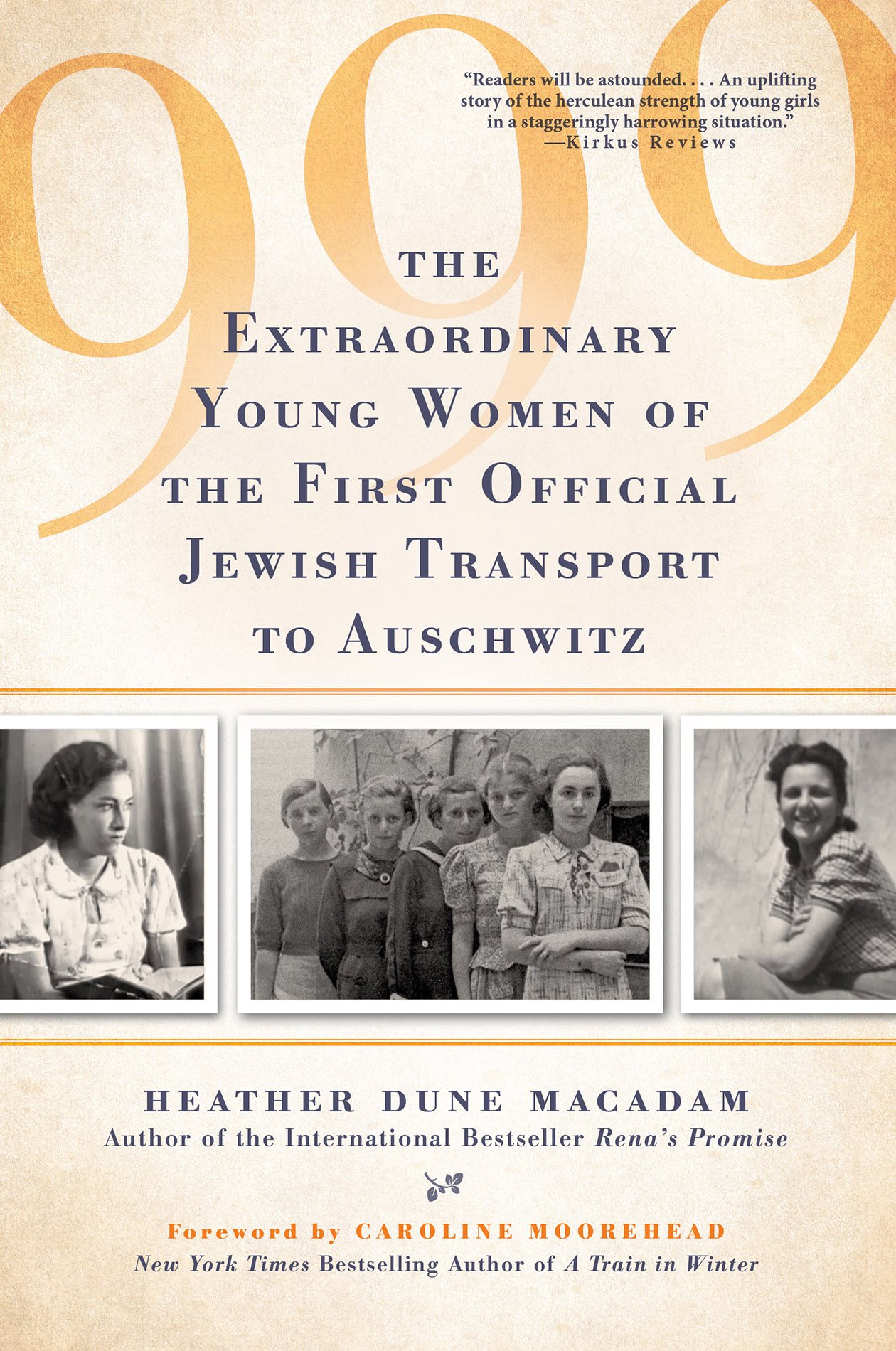

ALSO BY HEATHER DUNE MACADAM

Renas Promise: A Story of Sisters in Auschwitz The Weeping Buddha

The Extraordinary Young Women of the First Official Transport to Auschwitz

HEATHER DUNE MACADAM

CITADEL PRESS

Kensington Publishing Corp.

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

CITADEL PRESS BOOKS are published by

Kensington Publishing Corp.

119 West 40th Street

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2020 Heather Dune Macadam

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the publisher, excepting brief quotes used in reviews.

All Kensington titles, imprints, and distributed lines are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, educational, or institutional use.

Special book excerpts or customized printings can also be created to fit specific needs. For details, write or phone the office of the Kensington sales manager: Kensington Publishing Corp., 119 West 40th Street, New York, NY 10018, attn: Sales Department; phone 1-800-221-2647.

CITADEL PRESS and the Citadel logo are Reg. U.S. Pat. & TM Off.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8065-3937-9

ISBN-10: 0-8065-3937-2

First Citadel hardcover printing: January 2020

First trade paperback printing: February 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

Electronic edition:

ISBN-13: 978-0-8065-3938-6 (e-book)

ISBN-10: 0-8065-3938-0 (e-book)

for Edith

in memory of

Lea

&

Adela

For most of history, Anonymous was a woman.

V IRGINIA W OOLF

The measure of any Society is how it treats its

women and girls.

M ICHELLE O BAMA

Woman must write her Self: must write about

women and bring women to writing... Woman must

put herself into the textas into the world and into

history...

H LNE C IXOUS , The

Laugh of the Medusa

Foreword

BY CAROLINE MOOREHEAD

N O ONE KNOWS FOR CERTAIN , or will ever know, the precise number of people who were transported to Auschwitz between 1941 and 1944, and who died there, though most scholars accept a figure of one million. But Heather Dune Macadam does know exactly how many women from Slovakia were put on the first convoy that reached the camp on March 26, 1942. She also knows, through meticulous research in archives and from interviews with survivors, that the almost one thousand young Jewish women, some no older than fifteen, were rounded up across Slovakia in the spring of 1942 and told that they were being sent to do government work service in newly occupied Poland, and that they would be away no more than a few months. Very few returned.

Basing her research on lists held in Yad Vashem in Israel, on testimonies in the USC Shoah Foundations Visual Archives and the Slovak National Archives, and tracing the few women still alive today, as well as talking to their relatives and descendants, Macadam has managed to re-create not only the backgrounds of the women on the first convoy but also their day-to-day livesand deathsduring their years in Auschwitz. Her task was made harder, and her findings more impressive, by the loss of records and the different names and nicknames used, as well as their varied spellings, and by the length of time that has elapsed since the Second World War. Writing about the Holocaust and the death camps is not, as she rightly says, easy. The way she has chosen to do it, using a novelists license to re-imagine scenes and re-create conversations, lends immediacy to her text.

I T WAS ONLY in the late winter of 194041 that IG Farben settled on Auschwitz and its surroundings, conveniently close to a railway junction and to a number of mines and with plentiful supplies of water, for the construction of a major new plant in which to make artificial rubber and synthetic gasoline. Auschwitz was also given a mandate to play a role in the Final Solution of the Jewish question, a place where, alongside labor allocations, prisoners could be killed rapidly and their bodies as rapidly disposed of. When, in September, a first experiment using prussic acid, or Zyklon B, proved effective in the gassing of 850 inmates, Rudolf Hss, the camps first commandant, saw in it an answer to the Jewish problem. Since camp physicians assured him that the gas was bloodless, he concluded that it would spare his men the trauma of witnessing unpleasant sights.

First, however, the camp needed to be built. An architect, Dr. Hans Stosberg, was asked to draw up plans. At the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942, the Reich Main Security Office estimated that occupied Europe would yield a total of just under eleven million Jews. As Reinhard Heydrich, second in the SS hierarchy to Heinrich Himmler, put it, they should be put to work in a suitable way within the framework of the Final Solution. Those too frail, too young, or too old to work were to be killed straight away. The stronger would work and were to be killed in due course since this natural elite, if released, must be viewed as the potential germ cell of a new Jewish order.

Slovakia was the first satellite state to become a deportation country. For over a thousand years part of the kingdom of Hungary, and since the end of the First World War part of Czechoslovakia, it had become an independent country only in 1939, under German protection, ceding much of its autonomy in exchange for economic assistance. Jozef Tiso, a Catholic priest, became president, banned opposition parties, imposed censorship, formed a nationalist guard, and fanned anti-semitism, which had been growing since the arrival of waves of Jewish refugees fleeing Austria after the Anschluss. A census put the number of Jews at 89,000, or 3.4 percent of the population.

The order for unmarried Jewish women between the ages of sixteen and thirty-six to register and bring their belongings to a gathering point was not initially viewed as alarming, though a few prescient families made desperate attempts to hide their daughters. Indeed, some of the girls found the idea of going to work abroad exciting, particularly when they were assured that they would soon be home. Their innocence made the shock of arrival at the gates of Auschwitz more brutal, and there was no one there to prepare them for the horrors to come.

That same day, 999 German women arrived from Ravensbruck, which was already full with 5,000 prisoners and could take no more. Having been selected before leaving as suitable functionaries, they oversaw the young Jewish womens work of dismantling buildings, clearing the land, digging, and transporting earth and materials, as well as in agriculture and cattle raising, thereby freeing the men already at Auschwitz to work on the heavier tasks of expanding the camp. Coming from large and loving families, accustomed to gentle manners and comfortable living, the Slovakian women found themselves shouted at, stripped naked, shaved, subject to interminable roll calls in the freezing dawn, forced to walk barefoot in mud, fighting for rations, subject to arbitrary punishments, worked to exhaustion and often to death. They were hungry, sick, terrified. The female guards, from Ravensbruck, were later admitted by Hss to have far surpassed their male equivalents in toughness, squalor, vindictiveness and depravity. By the end of 1942, two thirds of the women on the first convoy were dead.