Contents

Guide

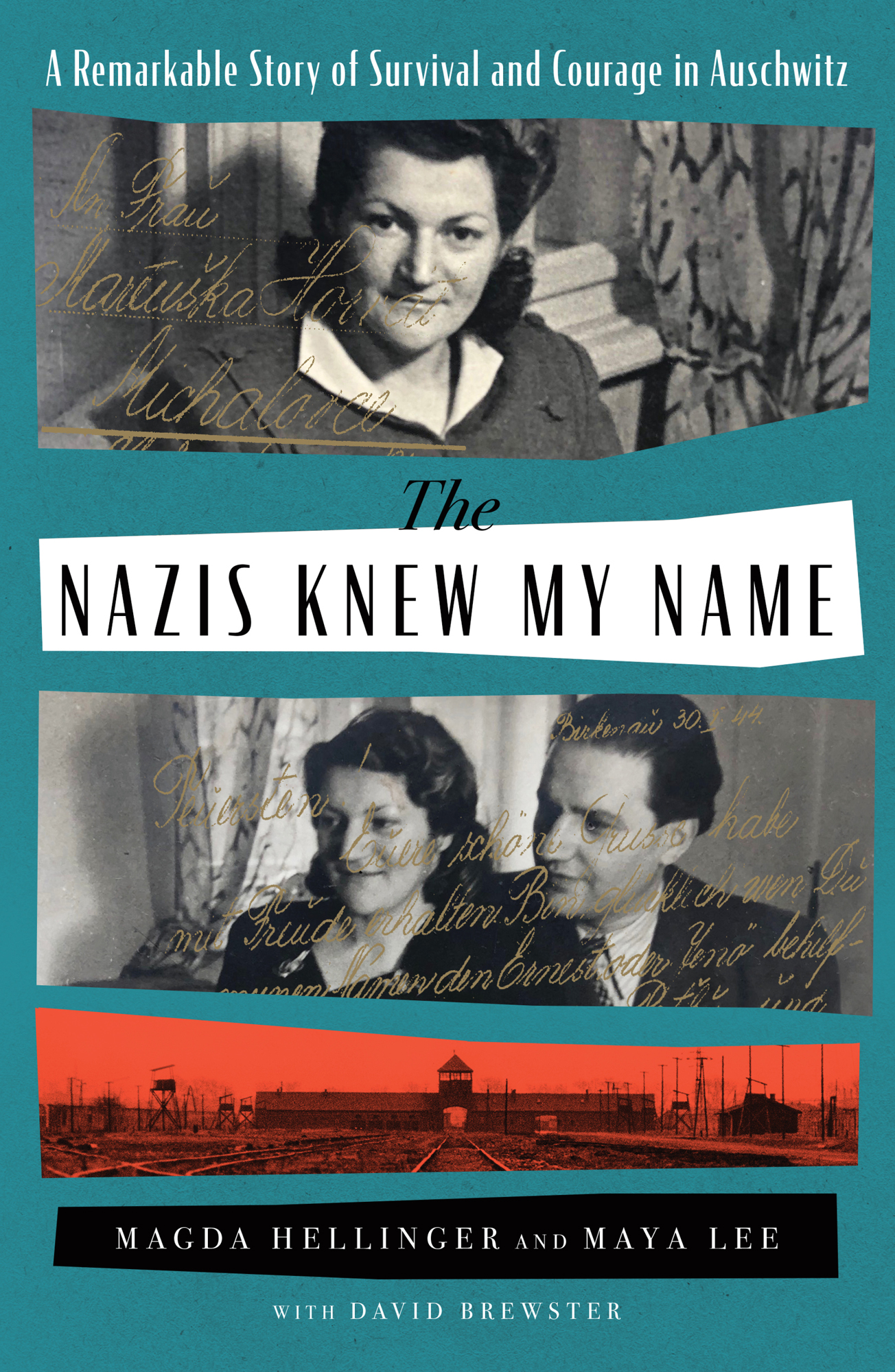

A Remarkable Story of Survival and Courage in Auschwitz

The Nazis Knew My Name

Magda Hellinger and Maya Lee

With David Brewster

In memory of my mother, Magda Hellinger Blau.

This is the story she always wanted to tell.

INTRODUCTION

V ery few can understand what it was like to be a prisoner at AuschwitzBirkenaureally only those who were there. Fewer still can understand what it was like to be forced into the role of prisoner functionary within the concentration camp. To find yourself in a position in which, if you were brave and clever, you might be able to save a few lives while being powerless to prevent the ongoing slaughter of most of those around you. To live with the constant awareness that, at any moment, you could lose your own life to a bored or disgruntled guard who perceived that you were being too kind to a fellow prisoner, when all you were doing was trying to be humane.

My mother, Magda Hellinger Blau, was one such prisoner, though for most of her life few, including most of her family, knew her story.

Magda was always an enigma. Despite all she went through, she was not like so many other survivors of the Holocaust who displayed the emotional scars of the experience for the rest of their lives. Magda was always forward-looking, positive, and industrious. As my sister and I grew up, she would tell occasional stories of the concentration camps and her unique role within them in the same matter-of-fact way that another mother might tell stories of growing up on a farm. We had no idea. Eventually we would just roll our eyes and say, Just leave it alone, Mum.

In the end, without telling any of us, she wrote and rewrote her story by hand. She finally employed a young man to transcribe her words into a typed manuscript, and only then did we have the chance to read them. But Magda wasnt interested in feedback or clarification. In 2003, at the age of eighty-seven, she took the file to a printer and had it produced as a slim book. She organized a book launch to support a charity she was involved with and sold a number of copies. And that was that.

For the final years of her life, my mother wouldnt be drawn on her story or on the topic of the Holocaust at all. Though there was more of the story to tell, shed had enough and wanted to move past the nightmare of collecting her memories. It was as though the act of writing it down had cleared her mind of any deep, smoldering trauma. She reverted to the mother I had known previouslythe one who only ever looked forward with purpose.

It was only after her death not long before her ninetieth birthday that I started to appreciate the complexity of my mothers story. In the late 1980s and early 1990s she had provided audio and video testimonies to the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Israel, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne, and, a few years later, the Shoah Foundation founded by movie director Steven Spielberg. She spent hours being interviewed for these projects but barely mentioned them to us. As I watched and listened to these recordings, it became clear that in her haste to get her story printed, my mother had omitted a lot of detail. She had also left out numerous primary sources that amplified her story, including the testimonies of some of the many women whose lives had been saved by Magdas careful manipulation of the Nazis. I realized that Magda had told only a fraction of her story in her own writings.

In the years since her death Ive become increasingly committed to gaining a better understanding of what Magda and those around her went through. Ive discovered a remarkable and unique story of a woman who had a rare, close-up perspective on the SS (the Nazis elite paramilitary Schutzstaffel) and their murdering, lying, and deceitful tricks, who somehow found the inner strength to rise above the cruelty and horror of the most notorious Nazi concentration camp, and who over three and a half years was able to save not only herself but also hundreds of others.

Little has been written about the people like Magda who were prisoners themselves while also holding positions of responsibility, at the behest of the SS, over other prisoners: the so-called prisoner functionaries of the concentration camps. What has been written tends to focus on the Kapos, who had particular responsibility over the Kommandosthe working groups who performed slave labor for the SS. Most of the Kapos were German prisoners, usually hardened criminals, who had a reputation for enormous cruelty. Unfortunately, this reputation meant other prisoner functionaries were tarred with the same brush. Magda has been misrepresented and judged unfairly by some survivors simply because of the positions she was forced to hold. Most of the accusations have relied on hearsay to denounce and condemn. In the early years after the Holocaust, Jewish survivors sought to challenge those who held such positions because they needed someone to blame. Many, including Magda, were accused of collaborating with the Nazis. This culture of finger-pointing has caused most people who held functionary positions to maintain their silence to avoid prompting further accusations.

However, to judge Magda or any of the other functionaries is to ignore the fact that they put their lives at risk every time they took some action that saved anothers life. Their stories need to be told.

Magda never sought thanks from those whose lives she savedsimply acknowledgment that she had done whatever she could in a truly horrific time. What she also wanted, as do so many other survivors, was to hold those who would deny the Holocaust to account. In her words, I have often wished for the chance to ask these people why they deny my suffering and discredit my life and that of millions of others. Did we not suffer enough that we should now have to listen to such denials? She also, like so many others, wanted to ensure that the Holocaust could never be repeated.

I turn to you readers, parents, teachers, professors, scientists, priests, rabbis. Educate the children and general public about the horrors perpetrated on all nations, not only Jews, under the Nazi regime. I cannot undo what was done to me and to countless others. The torment and nightmares wake me up every night when I close my eyes. I want to tell my story so people like you might become determined to ensure that the roots of such evil are never again allowed the grounds on which to spread.

Magda originally wrote her story as she recalled it. In her mind she was clear about events, about how she dealt with the SS monsters and her fellow prisoners. In retelling her story and filling out a picture of life in AuschwitzBirkenau during the years of her incarceration, I have attempted to remain as true to her memories as possible while adding the detail necessary to provide an honest but thorough account. In addition to Magdas writing and her recorded testimonies, I have drawn on the testimonies of other survivors who knew her and of others who held similar functionary positions, as well as on the work of various scholars. Where the truth is unclear, as it so often is in stories like this, I allow Magda to tell her story as she always told it from her own memory. This is particularly the case in personal interactions: dialogue recreated in this book is as Magda wrote or narrated it in her own testimonies, edited only for clarity where necessary.