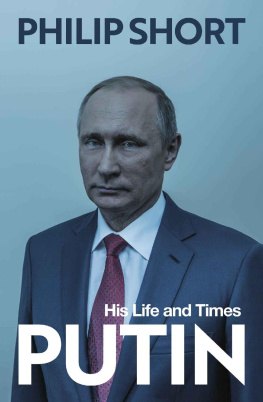

Philip Short - Putin: His Life and Times

Here you can read online Philip Short - Putin: His Life and Times full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Random House, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Putin: His Life and Times

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Putin: His Life and Times: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Putin: His Life and Times" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Putin: His Life and Times — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Putin: His Life and Times" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Philip Short has written authoritative biographies including Mao: A Life and Pol Pot: History of a Nightmare, following a long career as a foreign correspondent for the BBC in Moscow, Washington and other world capitals.

He spent eight years researching and writing this book, working mainly from sources within Russia, but also in Britain, France, the United States and a dozen other countries.

Banda

The Dragon and the Bear: Inside China and Russia Today

Mao: A Life

Pol Pot: The History of a Nightmare

Mitterrand: A Study in Ambiguity

For Romy, Ben and Sengan

Almost every language in use in the world today has a generally accepted form of transliteration into English. Russian does not. Although various romanisations exist, none has yet established itself as a universal standard, partly, perhaps, because most require special characters and diacritical marks. The result is a hodgepodge in which names are spelt in a bewildering variety of ways.

This book uses transliterations which are as close as possible to the way Russian words should be pronounced while conserving the original orthography. Since the Cyrillic alphabet has no equivalent of the English letter x, the romanisation ks is employed, as in Aleksandr, Aleksei, Ksenia, etc. Other letters not found in English include kh, pronounced as ch in loch, and zh, as in rouge. When a name ends in -ii, like Georgii or Dmitrii, pronounced as a single syllable, the letter y is usually substituted, thus Georgy and Dmitry. When -ii is pronounced as two syllables, as in Daniil, Gavriil or Mariinsky, it is written as such.

The trickiest letter of the Cyrillic alphabet is e, which can signify either ye as in Yeltsin, Yelena or Basayev or yo, as in Gorbachev and Khrushchev. Unfortunately there is no hard and fast rule. In most cases, e after ch and shch should be pronounced yo, except in words of Ukrainian origin, such as Chernenko, Chernobyl and names ending in -chenko (Kirichenko, Shevchenko, etc). There are exceptions, however, such as the playwright, Anton Chekhov. Other words where the pronunciation yo applies are so spelt, for example, Kishinyov, Seleznyov and Snegiryov. Everywhere else, e is pronounced ye, apart from a few place names, like Mount Elbrus, where in Russian a different form of letter e is employed.

The system is not foolproof. Purists may object that, to be consistent, Belyaev should be written Belyayev, but that would be too much of a mouthful and in any case the second y is elided. The other drawback is that it does not indicate where the stress should come in a name, but for that there are no fixed rules. In theory, the surname Borodin could be pronounced Brodin, Bordin or Borodn. In fact, the stress is on the last syllable, Borodn, but there is no way to guess that, you need to know.

Russian names always include the patronymic thus, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; his father, Vladimir Spiridonovich; his grandfather, Spiridon Ivanovich, and so on, the middle name deriving from the fathers given name. The combination of forename and patronymic is the polite form of address, Vladimir Vladimirovich in Russian being the equivalent of Mr Putin in English. For simplicity, patronymics are used here only when it is necessary to distinguish between individuals with the same first and family names, like Putin and his father, or when they appear in citations. For the same reason, the names of married women are given without a feminine ending: Lyudmila Putin rather than Putina, as would be written in Russian.

Even in ordinary times, Moscow is a hive of rumour and speculation. In the spring and early summer of 1999, it was so humming with conspiracy theories and tales of dark intrigue that the Russian adage, lies have short legs, meaning that they cannot run very far, seemed no longer to apply.

The President, Boris Yeltsin, a massively built, larger-than-life figure in his late sixties with a broad, impassive face and a shock of silvery hair, was ailing. A quintuple bypass operation three years earlier had pulled him back from the brink, but his health had deteriorated again and there were doubts, even within his own entourage, that he would survive the coming winter. His enemies were circling. The man who seemed most likely to succeed him, Yevgeny Primakov, two years his senior, who had served as Prime Minister and, earlier, chief of foreign intelligence, had left no one under any illusion that, once in power, he would attack not only the corrupt business magnates who had flourished in Yeltsins shadow but also those he considered to be their enablers in the Kremlin itself. Primakov, a bespectacled academic with jowls like a basset hound, was a tough, pragmatic conservative who had the support of the nomenklatura, the bureaucratic elite, and of the Communist Party. To the Family, the small group of intimates on whom Yeltsin increasingly relied and who in turn relied on him such an outcome would be, if not literally, then politically and materially, a death sentence. As the year progressed, it became more and more urgent for them to ensure that Primakovs rise was stopped.

The first hint of trouble brewing came at the end of May. Jan Blomgren, a veteran Swedish correspondent in Moscow, was told that the Kremlin was casting about for a pretext to postpone elections, due in December, for the lower house of parliament, the Duma, which were expected to result in a landslide for the Fatherland Party, whose members backed Primakov and his ally, the Mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov. Blomgren said later that he had two sources for the story, both with good access to the Presidential Administration. On June 6, 1999, he reported in the Swedish daily, Svenska Dagbladet, that several possibilities were being considered. Two involved changing the constitution, either to give greater independence to Russias 89 constituent regions, making the country a confederal rather than a federal state, or to consummate a long-discussed Union between Russia and Belarus, with Yeltsin as President and the Belarussian leader, Aleksandr Lukashenko, as Vice President. In either case, a new constitution would have to be written which would mean that the elections would be delayed.

The third possibility, Blomgren wrote, was to create a situation justifying the declaration of a state of emergency. That would be done through false-flag terrorist attacks that would be ascribed to militants from the autonomous republic of Chechnya, in the Caucasus, which had been in a state of insurrection for most of the previous decade.

Ten days later, another report appeared, this time in a Russian newspaper, Literaturnaya gazeta. The writer, Giulietto Chiesa, had spent 20 years in Moscow as the correspondent of the Italian Communist Party newspaper, lUnit, and later La Stampa. Chiesa also raised the possibility of terrorist attacks, which might be perpetrated by a secret service, either foreign or national in order to create panic among the population.

Hardly anyone took these reports seriously. They were just part of the cacophony of Moscow gossip. Eugene Rumer, then a young official at the State Department in Washington, did wonder about them. He and a colleague at the Bureau of Research and Intelligence debated whether to alert someone higher up. In the end, they decided not to. We thought it didnt quite rise to the level of writing a memo to anybody up the food chain, Rumer remembered. Afterwards I rather regretted that.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Putin: His Life and Times»

Look at similar books to Putin: His Life and Times. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Putin: His Life and Times and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.