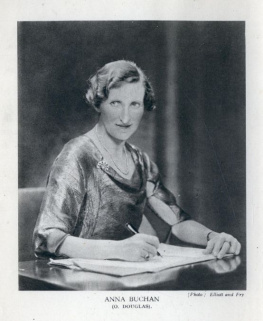

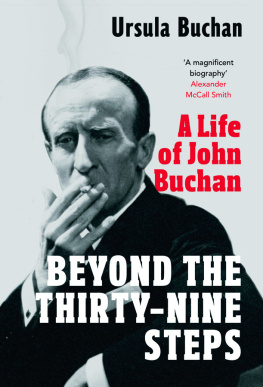

MY FATHER, THE REV. JOHN BUCHAN.

Walter and I were settled in the old house on the bridge, and we found a house for the parents on the hill just across Tweed Bridge. It had belonged to an artist, and there was a large room opening on the garden that had been used as {121} a studio. It made a splendid study, and Father had all his books round him, and the garden, in which he intended to make great improvements, at hand. The removal had been got over, the house had already a home-like look, and Anne-from-Skye (who had succeeded Marget) seemed inclined to like life at Peebles, so all was well, and we began to prepare for a holiday in Switzerland.

Since Violet's death we had enjoyed years of health and prosperity. So well did things seem to work out for us that people talked of 'the Buchan luck,' and I used to look pityingly at people on whom blow after blow fell, and wonder how they bore up at all. But few people get off unscathed, and our turn came.

On the day we started on our holiday Father looked rather tired, and before we reached London confessed to having a pain in his chest. John was dining with us at the Grosvenor, and telephoned for his own doctor who, when he had made an examination, said that Father must on no account travel. Walter and Alastair and I stayed on at the Grosvenor while the parents went to John's house in Bryanston Street. Father improved in a day or two and began to worry about Walter missing his holiday, so to please him the three of us crossed to France.

Happily we went no further than Paris, for the next day we got a wire telling us to come back at once as Father was very ill. It was a bad heart attack, and though he recovered from it, the doctors warned us that it might occur at any time, and that he must lead the quietest life with no work or hurry or excitement, and no walking except on the level.

It was a blow to him, for he had hoped in his leisure to help so many people, but he accepted it with a good grace, and managed to make of his restricted life something spacious and serene. It was a joy to him to be back in {122} Peebles, and able to take short walks through the fields he had played in as a boy, and feast his eyes on the hills he could no longer climb, to wander in the garden and note his special plants; to come in and write a chapter of his book, 'Peeblesshire Poets'; to read, sometimes, his little brown Baxter's Saints' Rest, or some story of high adventure, or his beloved Sir Walter; to enjoy the family life, and laugh like a boy at the foolish family jests. Some of the men who had been boys when he was a boy were still in the town. One of them, a notorious poacherwho in his sober senses passed his one-time companion with averted headif he had had rather much to drink would greet him jovially with a "Man, John, d'you mind yon big yin in the pool up Soonhope?"

It was a good thing Father was fairly well, because Mother's health was giving us anxiety. She was being treated for anmia, when she suddenly began to take bouts of fever; to all appearances quite well, she would shiver violently, and before we could get her upstairs and into bed she was delirious, with a temperature of 106. There seemed to be nothing we could do to ward off these turns, and they were a constant menace. It was so disappointing for her to get up her strength and be well enough to be downstairs, only to be thrown back.

She would say, "I'm at the foot of the precipice again," but she never lost her spirit.

It was a dreadful time, for no doctor seemed to know what was causing the fever. I often wished that Mother had been one of those women who seem positively to enjoy being ill and like having visits from doctors, but, like the boy in The Golden Age, she held the sacred art of healing in horror and contempt, and nurses she had no use for.

We had a very nice middle-aged one, but she had an {123} unfortunate taste for repeating poetry, and would try to soothe her patient off to sleep with

"The stag at e'en had drunk its fill..."

and that stag so got on Mother's nerves that I had to beg her to desist.

What a blessing that even in times of dire distress and anxiety there is always something to laugh at! Well or ill, Mother could not help being a comic. As Alastair said, trying not to cry, when the doctor told us he hardly thought she would live through the night, "If she weren't such a funny wee body!"

If Mother was rather a resentful patient, there was little of the ministering angel about me as a nurse. She complained that I shied hot-water bags into her bed, and there was truth in the accusation, but I had a lot on my head.

We had shut up the house that we had put right with so much pleasure in the spring, and all that winter the family lived with Walter. When Mother was able to take an interest in what was going on she would ask me searching questions about the servants, if everything was being done regularly, and about the housekeeping books, then would remark sadly that she feared there was a great leakage. I am sure there was, but I had neither my Mother's cleverness nor her experience, and was thankful simply to keep things going. The anxiety was very bad for Father, and we had to try to keep him as calm as possible. It was hard, too, on Alastair, with his horror of sadness, those recurrent crises, and in the holidays he just went about the house kicking things. Often Walter and I had to take turns of sitting up several nights in succession, as we did not care to leave Mother alone with a nurse when she was unconscious, and to pass the time and keep myself awake, I got out the MSS. I was writing about my experiences in {124} India. It was an escape from the unhappy present to go back into the sunshine of light-hearted days.

In the spring (1911) we felt something must be done. John had heard of Sir Almroth Wright, and thought we should bring Mother to London to see him. It seemed a great risk, but we decided to take it. Walter could be trusted to see that Father was well looked after, and we had two thoroughly good maids, so one morning in March Mother and I set off. We were going to Great-uncle John's house, alone now with Maud Mark, and that was like a second home to us all.

John was waiting at Euston, miserably wondering if an ambulance would be required, but Mother could always be relied on to play up in an emergency. There she was, smiling at him and saying she had enjoyed the journey.

Of course she paid for it. Two days later she went down with one of the worst bouts of fever that she had had, and in it Sir Almroth Wright saw her. We had been expecting a London doctor, very smart, with a manner, and it was extraordinarily comforting to see this tall, rather stooped man, with a somewhat shabby overcoat, who told us he had a mother of his own whom he would hate to lose. Later on he told John he had discovered what was wrong with Mother (some sort of germ attacking the blood), but whether she could be cured was doubtful.

We went to his house every four days for inoculation. It was too soon to say the treatment was doing good, but the change helped Mother, being in new surroundings, seeing different people. She had been kept on a very low diet, but Sir Almroth said she might eat anything, the more the better, and she enjoyed that. Maud was a wonderful stand-by. She got up herself very early (knowing that Mother slept badly), and appeared with a tempting breakfast tray.

{125}

In April Walter took his holiday. He and Alastair stayed at the Grosvenor, and Father came beside us, and we had a wonderfully pleasant time. Mother was able to enjoy motor runs to Windsor and Kew and other places, and generally we finished up with tea at Bryanston Street, where John was living. I even saw a few plays.