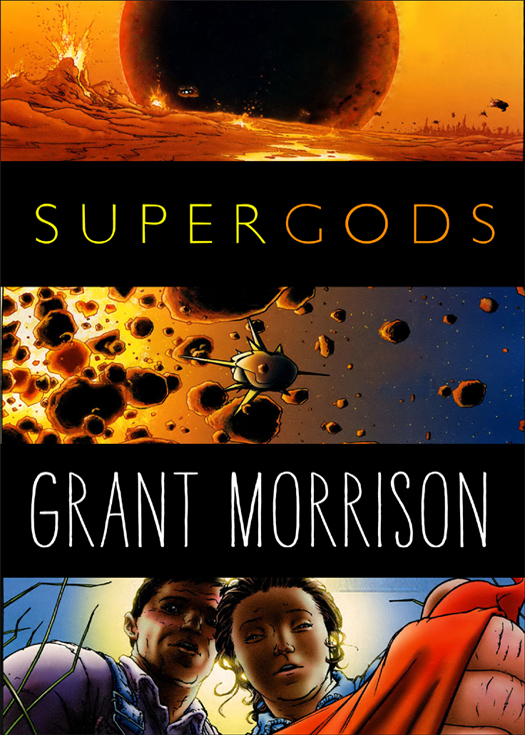

Copyright 2011 by Supergods Ltd.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

S PIEGEL & G RAU and Design is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

All DC Comics characters and images are & DC Comics.

All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60346-7

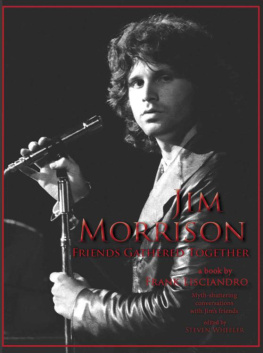

Front-case art: Frank Quitely, DC Comics Back-case art (left to right, top to bottom): Batman (art by Frank Miller), Spider-Man, Dr. Manhattan/Watchmen (art by Dave Gibbons); Superman/Action Comics (art by Joe Schuster), Grant Morrison (art by Cameron Stewart, courtesy of Arthur magazine), Green Lantern (art by Carlos Pacheo & Jesus Merino); Wolverine, Captain America, Wonder Woman (art by Brain Bolland); WE3 (art by Frank Quitely), Cyclops, Superman (art by Frank Quitely); Hulk, The Flash (art by Francis Manapul), Aquaman (art by Jose Garcia Lopez)

SUPERMAN, BATMAN, WATCHMEN, GREEN LANTERN, WONDER WOMAN, THE FLASH, and AQUAMAN are all & DC Comics.

All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission. CAPTAIN AMERICA, SPIDER-MAN, WOLVERINE, HULK, and CYCLOPS and Marvel Entertainment, LLC. All Rights Reserved and Used with Permission.

www.spiegelandgrau.com

Jacket design: Will Staehle

v3.1

For Kristan, supergoddess

Behold, I teach you the superman: He is this lightning, he is this madness!

Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra

FOUR MILES ACROSS a placid stretch of water from where I live in Scotland is RNAD Coulport, home of the UKs Trident-missile-armed nuclear submarine force. Here, Ive been told, enough firepower is stored in underground bunkers to annihilate the human population of our planet fifty times over. One day, when Earth is ambushed in Hyperspace by fifty Evil Duplicate Earths, this megadestructive capability may, ironically, save us allbut until then, it seems extravagant, somehow emblematic of the accelerated, digital hypersimulation weve all come to inhabit.

At night, the inverted reflection of the submarine dockyards looks like a red, mailed fist, rippling on a flag made of waves. A couple of miles of winding road from here is where my dad was arrested during the antinuclear protest marches of the sixties. He was a working-class World War II veteran whod swapped his bayonet for a Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament badge and became a pacifist Spy for Peace in the Committee of 100. Already the world of my childhood was one of proliferating Cold War acronyms and code names.

And the Bomb, always the Bomb, a grim and looming, raincoated lodger, liable to go off at any minute, killing everybody and everything. His bastard minstrels were gloomy existentialist folkies whining horn-rimmed dirges about the Hard Rain and the All on That Day while I trembled in the corner, awaiting bony-fingered judgment and the extinction of all terrestrial life. Accompanying imagery was provided by the radical antiwar samizdat zines my dad brought home from political bookstores on High Street. Typically, the passionate pacifist manifestoes within were illustrated with gruesome hand-drawn images of how the world might look after a spirited thermonuclear missile exchange. The creators of these enthusiastically rendered carrion landscapes never overlooked any opportunity to depict shattered, obliterated skeletons contorted against blazing horizons of nuked and blackened urban devastation. If the artist could find space in his composition for a macabre, eight-hundred-foot-tall Grim Reaper astride a flayed horror horse, sowing missiles like grain across the snaggle-toothed, half-melted skyline, all the better.

Like visions of Heaven and Hell on a medieval triptych, the postatomic wastelands of my dads mags sat side by side with the exotic, triple-sunned vistas that graced the covers of my mums beloved science fiction paperbacks. Digest-sized windows onto shiny futurity, they offered android amazons in chrome monokinis chasing marooned spacemen beneath the pearlescent skies of impossible alien worlds. Robots burdened with souls lurched through Day-Glo jungles or strode the moving steel walkways of cities designed by Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and LSD. The titles evoked Surrealist poetry: The Day It Rained Forever, The Man Who Fell to Earth, The Silver Locusts, Flowers for Algernon, A Rose for Ecclesiastes, Barefoot in the Head.

On television, images of pioneering astronauts vied with bleak scenes from Hiroshima and Vietnam: It was an all-or-nothing choice between the A-Bomb and the Spaceship. I had already picked sides, but the Cold War tension between Apocalypse and Utopia was becoming almost unbearable. And then the superheroes rained down across the Atlantic, in a dazzling prism-light of heraldic jumpsuits, bringing new ways to see and hear and think about everything.

The first comic shop in the UKThe Yankee Book Storeopened in Paisley, home of the pattern, just outside Glasgow in the years after the war. With a keen sense of ironic symmetry, the comics arrived as ballast alongside the US service personnel whose missiles threatened my very existence. As early R&B and rock n roll records sailed into Liverpool to inspire the Mersey generation of musicians, so American comics hit in the west of Scotland, courtesy of the military-industrial complex, to inflame the imaginations and change the lives of kids like me.

The superheroes laughed at the Atom Bomb. Superman could walk on the surface of the sun and barely register a tan. The Hulks adventures were only just beginning in those fragile hours after a Gamma Bomb test went wrong in the face of his alter ego, Bruce Banner. In the shadow of cosmic destroyers like Anti-Matter Man or Galactus, the all-powerful Bomb seemed provincial in scale. Id found my way into a separate universe tucked inside our own, a place where dramas spanning decades and galaxies were played out across the second dimension of newsprint pages. Here men, women, and noble monsters dressed in flags and struck from shadows to make the world a better place. My own world felt better already. I was beginning to understand something that gave me power over my fears.

Before it was a Bomb, the Bomb was an Idea.

Superman, however, was a Faster, Stronger, Better Idea.

Its not that I needed Superman to be real, I just needed him to be more real than the Idea of the Bomb that ravaged my dreams. I neednt have worried; Superman is so indefatigable a product of the human imagination, such a perfectly designed emblem of our highest, kindest, wisest, toughest selves, that my Idea of the Bomb had no defense against him. In Superman and his fellow superheroes, modern human beings had brought into being ideas that were invulnerable to all harm, immune to deconstruction, built to outsmart diabolical masterminds, made to confront pure Evil and, somehow, against the odds, to always win.