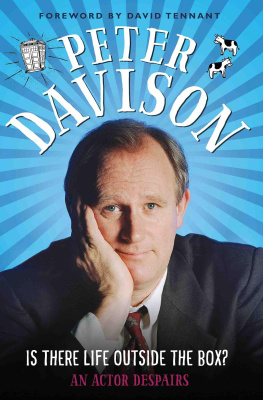

BY DAVID TENNANT

A s a child who grew up obsessed with television, I recall Peter Davison was absolutely all over my childhood. Of course there were only three channels in those days. That ballooned to four in the heady days of 1982 when the launch of Channel 4 made us feel drunk with choice, but there werent a lot of different things to watch, and as a child who spent hours in front of the box, with an undiscerning capacity for consuming anything that came on, Peter Davison seemed to feature in a disproportionately large number of programmes.

I am sure he was in three different sitcoms at the same time, there was definitely an advert or three most significantly the slightly space-age one about...was it saucepans? And then of course there was All Creatures Great and Small the Downton Abbey of its day, which was a massive hit across the nation, and in our house. Somehow this story of a gentler time, of an England carved in jaw-dropping countryside and peopled with honest, simple folk struck a chord in post-industrial Paisley, as it did across the nation. My mum loved it, and of course she particularly loved the youthful, slightly cheeky blonde-ish one: the winsome Tristan Farnon, everyones favourite.

To be perfectly honest, All Creatures Great and Small annoyed me. It was on at the same time as The Muppet Show and there was no such thing as a video recorder or a second television to allow diversity of viewing in the house. As a fairly annoying eight-year-old my viewing habits were usually indulged, but an exception was made for All Creatures. I was outnumbered and Sunday nights were all about the vets, the rolling hills and lovely, fresh-faced Tristan.

But then of course in 1981 it all changed and Peter was announced as the next face of Doctor Who. Although he had been part of the televisual furniture for as long as I could remember, he was suddenly plopped into the centre of my ten-year-old world. Tom Baker had been the Doctor since I was tiny, he was the only one I really knew. I understood that it was a revolving door and that other actors could take the part but I had never lived through that. I had pictures of Tom on my bedroom wall, my granny had knitted me a long multi-coloured scarf. Could a new Doctor ever mean as much, ever make the TARDIS fly with quite the same excitement?

I can still taste the sense of anticipation and excitement and nervousness I felt sitting down to watch the first episode of Castrovalva. It was just after Christmas, only a couple of days into 1982. It was initially so disconcerting to see a different face stream through that famous title sequence. How could this be the Doctor? Could we ever get use to this fresh-faced pretender? He had floppy hair and no scarf. He was all breathless energy and confounded enthusiasm. This wasnt right. Could I ever accept this?

It took me about two episodes. My granny knitted me a cricket jumper.

Then a lot of years passed. Lots of other things happened to me and to TVs Peter Davison and it isnt for me to go into them all here because a lot of it is about to be covered in the book you are now holding. Suffice to say that Peter Davison continues to be a big presence in my life, not only because he is still all over the telly, and on stage and on the radio, but more significantly he is also the grandfather of my children.

I dont know what the odds of this happening are. Its a weird quirk of fate, or possibly a stutter in the space-time continuum that has led me here. Yet for all its unlikeliness it all makes a sort of sense. You might occasionally meet the people who influenced you as a child and that can be gratifying or disappointing depending on the individual or the circumstances. It is pretty rare to find yourself related to one of them.

My ten-year-old self would be, I think, delighted, if not a little mystified.

My forty-five-year-old self is, I am sure, delighted and still a little mystified.

I cant wait to read this book not least to find out if he says anything about me but also because after thirty-five years I remain a fan.

Peter is a great actor, a beloved granddad and a lovely man.

I feel very lucky that he has been such a constant presence in my life, in such a variety of unlikely ways.

Thank you Peter. Well done for finishing the book and can you babysit Friday night?

DT

W here do I start? More particularly, given that Im still breathing, and available for work, where do I finish? And anyway, how much of what I remember will be of interest to anyone, other than my children (at some point in the future obviously), or those searching for actionable libels, and the most devoted followers of certain iconic TV series?

Its hard work too. Im not a writer, which makes the decision to eschew the services of a proper one all the more questionable. Instead, my friend Andy Merriman, who years ago had written a radio series I was in, and who now cannot avoid blame for this book as it was his idea in the first place, has dispatched himself to all parts of the kingdom to interview friends and family, hoping their fragmented memories will fill in the gaps in mine. This has presented its own problems as it turns out no two people have the same memory of the same event. Apparently, this is the case even if the event happened yesterday let alone fifty years ago. So when I have come across contradictions which havent been ironed out by a light bulb switching on in my head and me leaping from my chair and exclaiming, Yes, thats right, of course it is!, I have trusted my own recollections over those of others. Partly because I have the usual conviction that I am always right, and partly because where the odd disputed memory has surfaced, closer examination has often revealed I was right (although I admit the closer examination was done by me).

None of which matters because its my book. Go and write your own.

All the words in it are my own, although Im sure, before you read this, Andy will have taken a view on the exact order they end up in. Im also grateful to my wife Elizabeth, who whenever Ive asked her to read a page or two, hopeful of a bucketful of praise, has spent her time adding or subtracting commas, apostrophes (are you sure thats right, Elizabeth?) and full stops.

Not being a writer, I then made the huge mistake of reading other autobiographies. I stuck to those actually written by the subject, which, while illuminating, became a depressing exercise when comparing them with my own efforts. There was the politician whose vivid account of childhood deprivation in London made my own South London, lower-middle-class, walk-in-the-park life seem trivial. Then there was the writer and comedian whose brilliantly funny and honest book was only marred by him spelling my name wrongly on page 22.

Finally, there was Mark Twain. Two volumes of it. Big fat books which, at his insistence, remained unpublished until a hundred years after his death, to be absolutely sure everybody mentioned in it would be properly dead.

This was either an overly cautious man or one who showed enormous confidence in the advancement of medical science in the twentieth century. He started writing his life story at the age of forty-two (two years after the ideal age, he was told), stopped, started again, stopped for a bit longer, and thirty-three years later had finally figured out how to do it.

This is one of the greatest writers of all time - what chance do I have? I am already twenty-two years behind schedule, and my original plan of starting at the beginning, and proceeding in an orderly manner has been blown out of the water by Twains moment of epiphany. In June 1906 he announced the right way to do an autobiography was to start at no particular time of your life, and wander about all over it, talking only about what interests you, and stopping the moment youre bored, or when something else interesting comes to mind. When I read this, I sprang up from my chair exclaiming, Yes, thats right, of course it is!