For Bets

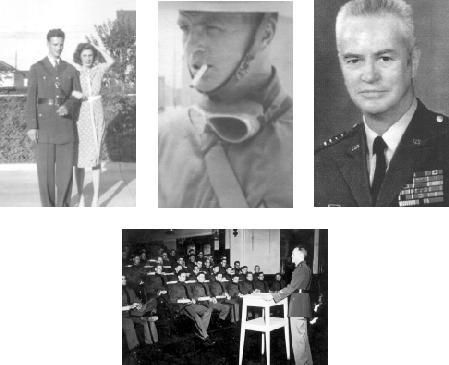

Clockwise from left:

Don and Bets at Fort Sam Houston

North Africa, 1942

General Bennett around the time of his retirement

Don ( front right ) in a West Point classroom

1

Childhood and Early Years

I was born on May 9, 1915, in the small town of Lakeside, Ohio, located a dozen miles or so outside of Toledo. Lakeside was like a thousand other towns of the Midwest in those years, one foot still firmly planted in the nineteenth century, the other foot just beginning to edge into the twentieth.

When I was about a year old, we moved to Genoa, and then several years later to Oak Harbor.

Where I grew up had only one church, Methodist, which my family went to every Sunday. The local school had three hundred or so students, from kindergarten to twelfth grade all in one building. They were just starting to pave the streets, news came via the paper from Toledo or telegraph, and my fathers job was supervising the stringing of electrical lines and the powering of the trolley that connected us to the rest of the world.

As I write this now, eighty-six years later, it seems that I was born into a far different world, and I am stunned by how quickly it changed and the role I played in creating some of that change.

When I was a boy, veterans of the Civil War were a common sight. That war was only fifty years past. The men in blue uniforms, who seemed so ancient to me then, were younger than I am now. Bull Run, Gettysburg, Shiloh, Appomattox were not just names in history books, they were memories still alive in the hearts of millions of Americans. On Decoration Day tears still flowed when flowers were laid upon graves of comrades who died in such distant places as Virginia and Georgia.

When I graduated from West Point and went to my first posting at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, I was trained in how to lead a team of horses pulling an artillery piece, riding one of the trace horses, learning the lesson all old artillerymen knew, to keep your right foot high and out of the stirrup, otherwise it might be crushed by the guide pole.

Only four years after learning that lesson I was in command of a mechanized battalion of armored artillery at Omaha Beach. That one battalion had more firepower than all the artillery pieces fired at Gettysburg. Only five years after Omaha, I witnessed the detonation of an atomic bomb in Nevada. And but ten years after that, I personally was responsible for hundreds of such weapons deployed in Germany. That is how quickly my world, our world, changed.

My family came to America from England. My father, Louis Bennett, was born in the 1890s. He never knew who his father was. Only one person knew for sure, his motherat least we think she was my fathers mother. There were some rumors that, in fact, my real grandmother, Dads mother, had given him away to a friend, Grandmother Bennett swearing her to secrecy about who she and the father really were. For reasons well never know, Grandmother Bennett never once talked about it, taking the secret to her grave. It had the aura of a Victorian novel about it, and my sisters and I found it all quite mysterious and exciting. We liked to assume that our mystery grandparents, in England, were royalty. Who knows, maybe they were.

When Dad was seventeen, he went to work in the new high-tech industry of that day, wireless telegraphy, and actually apprenticed under the legendary Marconi, helping to build the first transatlantic radio station in England.

Dads mother, Grandmother Bennett, was good friends with the Jackas, a family who had moved from England to Canada and from there to Ohio. They invited Dad and Grandmother to come over, and in 1909 they made the move.

My father, like so many others, came to America and landed at Ellis Island. I have often thought about the strange twists of history. Thirty-five years later I would go to England as part of the greatest invasion force in history, one of millions of Americans preparing for D day. If fate had been slightly different, I might have been in the British army instead, perhaps to fight and die at Dunkirk or at El Alamein.

The Jackas were an interesting family. They had a daughter who most certainly caught the interest of my father. Her name was Mary Grills Jacka, and she would be my mother.

Grandpa Jacka was born in Capetown, South Africa, long before the start of the Boer War. He became a sailor, then a minister, and finally wound up working in a limestone quarry in Lakeside, Ohio.

My mother had four brothers, all of whom went into the army during World War I. One of them was badly gassed and never really recovered.

My mother was a handsome woman, strong in character and faith. She eventually had four children, my older sister Florence, then me, and then my younger sisters, Rosemary and Margaret.

My first memories of my father were that he was an important man in town. He was, to that age, the master of a high-tech wonder, electricity, a position as mysterious to some as someone who today builds and runs complex computer systems.

Having worked for Marconi, my father quickly landed a job with the power company and was soon responsible for laying out the electrical grid to the small towns and farming communities surrounding Toledo. The power company also ran the trolley lines. I remember riding the trolleys with my father and mother as a small boy, proud that my father was responsible for the juice that made them run.

As I look back, I realize we were far better off than many. We actually owned an automobile, my father needing it so he could get around to the different work sites. We had a telephone, and even a radio, in fact, the first radio in town.

It was a crystal set that my father built himself, baking the crystal coil in the kitchen stove. He set up a sixty-foot-high pole in the backyard and from it strung an aerial into the house. In the evening Dad would carefully adjust the set, and if conditions were right, we might pull in WJR across the lake in Detroit or even KDKA out of Pittsburgh.

Neighbors would come over and gather around the tiny speaker, awed by this new wonder that could carry voices, news, and music from hundreds of miles away. Of course, no one was allowed to touch the set. That was my fathers domain.

As I think about all that I eventually moved on to, command of a battalion in combat, the rank of a four-star general, commander of hundreds of thousands of troops, and adviser of presidents, I am grateful for that small town, and that world that I grew up in.

It was a tight-knit world. We all knew each other, knew who could be counted on in times of trouble, knew whose word was always a solemn pledge, knew who had strength and who did not.

It was a world that some today might find constricting, for it is chic and popular today to dismiss the values of small-town America of that time. But I was grateful for it and shall treasure its memories and all that it taught me.

I learned at a very early age that if a boy gave his word, he was expected to keep it. If he failed to do so, everyone knew, his teachers, the minister, the local policeman, the neighbors, and eventually his parents. As a child, if I got into some mischief or trouble, by the time I got home my parents already knew about it, and punishment awaited.

A man, even at the age of seven, was expected to be respectful of elders, look out for the welfare of his sisters, and share with those less fortunate. If told to do a job, he did it.