Contents

Guide

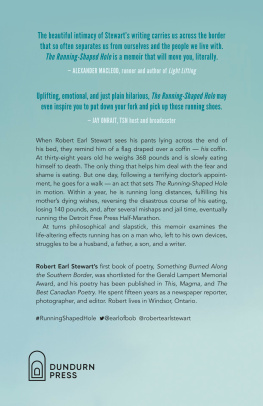

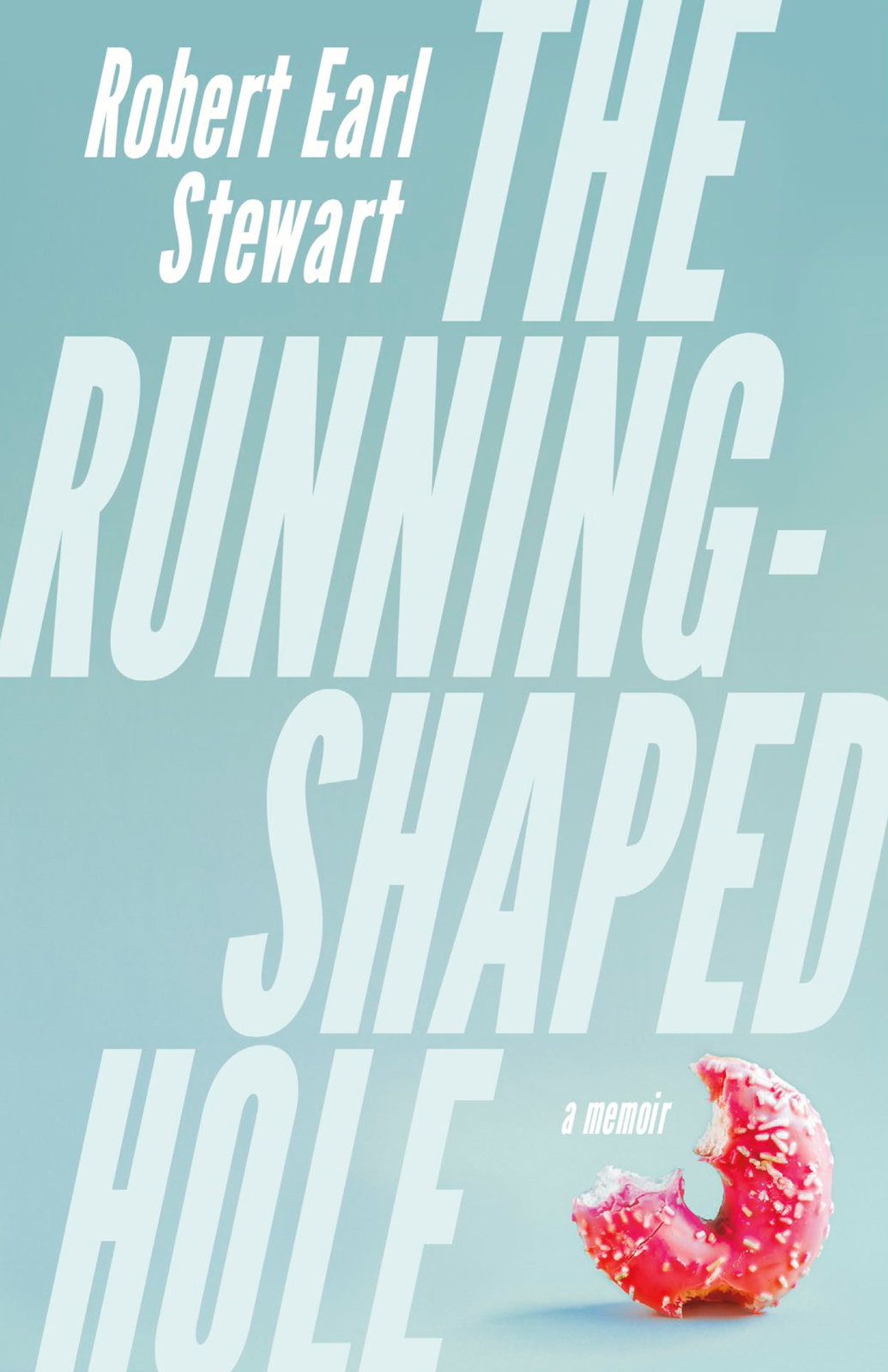

THE RUNNING-SHAPED HOLE

Robert Earl Stewart

THE RUNNING-SHAPED HOLE

a memoir

Copyright Robert Earl Stewart, 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purpose of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Publisher and Acquiring Editor: Scott Fraser | Editor: Dominic Farrell

Cover designer: Laura Boyle

Cover image: unsplash.com/Birgith Roosipuu

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: The running-shaped hole : a memoir / Robert Earl Stewart.

Names: Stewart, Robert Earl, 1974- author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210337230 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210337249 | ISBN 9781459749054 (softcover) | ISBN 9781459749061 (PDF) | ISBN 9781459749078 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Stewart, Robert Earl, 1974-Health. | LCSH: Stewart, Robert Earl, 1974- | LCSH: Runners (Sports)CanadaBiography. | LCSH: Overweight menCanada Biography. | LCSH: Weight loss. | CSH: Authors, Canadian (English)Biography. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC GV1061.15.S74 A3 2022 | DDC 796.42092dc23

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Ontario, through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and Ontario Creates, and the Government of Canada.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

The publisher is not responsible for websites or their content unless they are owned by the publisher.

Dundurn Press

1382 Queen Street East

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4L 1C9

dundurn.com, @dundurnpress

For my mother, a promise made.

And for my father, a promise to my mother.

What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself.

Blaise Pascal, Penses

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

A DEATHBED PROMISE

WHILE SHE WAS lying on her deathbed, my mother asked me to promise her that I would lose weight and get in shape.

But even as she lay there at fifty-eight years old, dying from an insidious Cytomegalovirus infection that was devouring her organs, I denied her that promise. I had the gall to make an excuse. Sitting at the foot of her hospital bed that June day in 2006, I looked into her desperate, dying face and told her, I just dont have the time. Im just too busy too busy being a writer who hadnt really written anything yet; too busy being the editor of a weekly newspaper. I was too puffed up on my own self-importance to realize what a terrible son I was being.

I wasnt a child. I was thirty-two years old. And I sat there in a chair pulled up to the foot of a hospital bed that my mother would never leave, too sad and afraid to make eye contact with the person who had brought me into this world. My father sat at the head of the bed, holding my mothers hand. I heard my name escape his lips, whispered with exasperated disgust.

One could argue that my inability to make that promise to my mother stemmed from my wanting to remain in a state of denial about her health, wanting to pretend, even if only for a bit longer, that my mother was not dying. Making a promise of that magnitude seemed tantamount to admitting that this was, in fact, her deathbed. If I could persist in a state of stubborn self-delusion about my weight, which at the time was topping three hundred pounds, and the impact it had had on my health for years on end, then surely I could also imagine a world where my mother convalesced; where the person I loved did not incrementally disappear from her body; where she did not linger through emergency surgeries in which long tracts of her intestine were removed; where death did not become the best option; where death did not take her from us too soon. Promising something, anything at all, in the dire confines of Intensive Care just seemed too final, too terrifying, too real. Living in that state of denial was a way to insulate myself from my guilt a guilt I would never be able to escape, of course, as it would descend on me like a shroud of shame whenever I recalled my failure at the foot of her hospital bed, which was often.

Thats no kind of answer, said my father, once my mother had closed her eyes and slipped into over-drugged unconsciousness. His own eyes were puffy and red with grief. We were only a week into what would become a torturous five-month decline. Would it kill you just to make a little effort?

I wanted to tell him that it might but knew this was not the time. I just dont know when I would fit it in, I whined. Getting in shape? Thats a lot of work, and Ive got the newspaper, and the boys, and Jen and the baby I was quickly out of excuses, and my excuses were all excellent reasons to put some effort into my health both physical and mental.

Everyone knows the sound their father makes when he is disgusted with you for failing to clean up your bedroom, for having your second bike stolen in a single summer, for being caught with a dubbed cassette copy of the Beastie Boys Licensed to Ill, for coming home drunk for the fifteenth time in high school That was the sound he made then as he turned away from me to place a cool cloth to my mothers fevered brow.

Thats all she wants from you, Bobby, he said, choking back sobs. She wants you to be happy and healthy. Apparently, thats too much, though.

What would have been the real harm, Ive always wondered, in saying Okay, Mom, I promise, whether I meant it or not, when hanging in the balance was some thread of hope and happiness for a terminally ill woman: a vision of her adult son, healthy and hale, instead of the bloated gastropod slumped in embarrassment at her perfect feet. The harm, I knew, was that if I promised to lose weight, to exercise and eat right promises I had made to myself many times, in vain I might actually have to make some monumental changes, whether she lived to see them or not.

So, I stayed too busy.

She was too weak to argue with me, but my mother wore her deep disappointment and her sadness on her face. She may not have been able to eat, but she could still be mad at her son.

Flash forward to November 2012. Im driving northbound on Howard Avenue in Windsor. Im thirty-eight years old. I weigh 368 pounds. Ive just left an appointment with a cardiologist, and Im crying my eyes out behind the wheel of my minivan. My mother has been dead for six years. She slipped away on an October day in 2006 while my dad walked from the hospital to their nearby home to eat supper. At the time, I was likely fresh in the door from work at the newspaper, on my hands and knees digging a Luke Skywalker action figure out from under our old upright grand piano with a school ruler. The phone rang; my wife, Jennifer, answered and after a too-brief conversation handed me the phone. The tears of what she feared was true rolled from her eyes while our son Nathanael, four at the time, stood looking up at me while I listened to my crying father tell me my mother was gone.