This book made available by the Internet Archive.

Foreword

Paul Soros

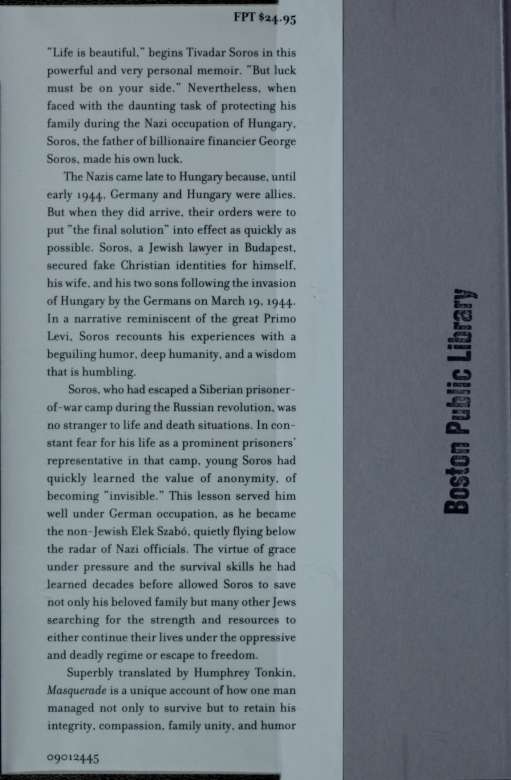

Tivadar, my father, was always an unusual and original person. He had great judgment, based on a deep understanding of the world and of human nature. 'It is amazing how well people can bear the suffering of others' was one of his typical comments that stick in my mind.

His set of values, of what is or is not important in life, the ability to see things as they really were, not as they appeared to be, were formed not by middle-class beliefs, conventions or ambitions, but by his experiences of survival during the Russian Revolution as an escaped prisoner of World War I.

I have observed that it is often when playing bridge or competitive tennis, or when money is involved, that the true nature and personality of someone reveals itself. The public persona of high moral standards, generous and gracious, may reveal cracks, offering a brief glimpse of what the individual is really made of.

The period described in this book was more revealing than a mere bridge game, because the stakes were truly life and death. I hope the reader will gain the same impression I had as a participant - no matter how mad or threatening the world and society, or how difficult the circumstances, a responsible person must try to cope, not follow like a sheep, but take control of the direction of his or her destiny. My father did, managing to remain a civilized

and humane person, without capitulating to fear or hate, keeping his dignity and cool, doing his best for his family and fellow humans in danger.

In 1956, he escaped from Hungary and made his way to the United States. There he decided to write a book about his experiences during the Holocaust period, as he had done with his earlier adventures in Russia. As Maskerado this was published in 1965 in Esperanto, a language he had learned in World War I. In 1998, my daughter-in-law, the writer Flora Fraser, came across a family copy of a very rough English translation of Maskerado. Enamored with Tivadar's story, she envisioned the appeal of an English publication. Her unstinting editorial efforts led to collaboration with Professor Humphrey Tonkin, of the University of Hartford, Connecticut. He has now produced a more polished translation into English, provided a fascinating commentary on the background to Tivadar's story, and thereby given Maskerado a new life and a wider audience.

I was eighteen at the time my father describes, old enough to comprehend, young enough to learn. Having been fortunate to survive, I have no doubt that these were the formative experiences shaping the rest of my life.

Foreword

George Soros

I cannot be objective about this book. It deals with the formative period of my life and it is written by my father who was the most important figure in my life at that time. The book brings back memories which are sharply etched in my mind, more sharply than anything else that happened to me.

The Germans occupied Hungary on March 19, 1944. We were liberated by the Russians on January 12, 1945. During those ten months we lived in mortal danger. More than half the Jews living in Hungary, and perhaps a third of the Jews living in Budapest, perished during that time. I and my family survived. Moreover my father helped a large number of other people in a variety of ways. This was his finest hour. I had never seen him work so hard. As a lawyer he prided himself on working as little as possible. When his most important client, the landowner Okanyi Schwartz, considered engaging him, he was advised against it on the grounds that my father spent most of his days in the swimming pool, on the ice rink or in cafes. He used to run his office out of his home and it was a rare occasion when there were people in the waiting-room; during the German occupation, the rented room which four of us shared in Vasar utca could be approached only through the bathroom: the bathroom was often crowded with people waiting to seek his advice.

Masquerade

It is a sacrilegious thing to say, but these ten months were the happiest times of my life. I was fourteen years old. We were in great peril, but my father was seemingly in command of the situation. I was aware of the dangers because my father spent a lot of time explaining them to me but I did not believe in my heart of hearts that I could get hurt. We were pursued by evil forces and we were clearly on the side of the angels because we were unjustly persecuted; moreover, we were trying not only to save ourselves but also to save others. The odds were against us but we seemed to have the upper hand. What more could a fourteen-year-old want? I adored and admired my father. We led an adventurous life and we had fun together. I think some of that feeling comes through in the book but my father was far too modest to brag about how many people he helped.

My father was exceptionally well-prepared to cope with the German occupation because he had lived through a somewhat similar experience earlier in his life. In the First World War he escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp in Siberia and got caught up in the Russian revolution. He learned how to survive in a situation where the normal rules do not apply. The experience transformed him. He had started out as an ambitious young man eager to get ahead in the world. In the prisoner-of-war camp he established a wall newspaper, called The Plank, which made him so popular that he was elected the prisoners' representative. When in a neighbouring camp some prisoners-of-war escaped, the camp commander executed the prisoners' representative in retaliation. This made him realize that it is not always so healthy to be prominent. Rather than awaiting his fate placidly, he decided to organize an escape. He chose people with the appropriate skills: cooks, carpenters and so on. His own skill lay in leadership. He did not pride himself on actually doing anything. The plan was to cross the mountains, build a raft and drift down to the ocean. There was only one thing wrong with it. All the rivers of Siberia drain into the Arctic Ocean. They drifted for several weeks before they realized that they were getting further and further north. And it took them

several more months to fight their way back through the taiga. In the meantime the Russian revolution had broken out and there was fighting again. The Reds killed those who had aligned themselves with the Whites and vice versa. This was the time when a brigade of escaped Czech prisoners-of-war roamed over the trans-Siberian railroad in an armored train. After many adventures my father managed to get away from Siberia to Moscow. Eventually he found his way back to Hungary. He recounted his adventures in a book similar to this one entitled Modern Robinsons (Crusoes in Siberia).