H elp in preparing the translation and in gathering the notes came from numerous individuals and organizations. A year as a visiting scholar at the Whitney Humanities Center at Yale University gave me time to work on the project in addition to my other research and reading, and I am very grateful to the staff of the Sterling Library at Yale and the Mortensen Library at the University of Hartford for their many favors. Detlev Blanke, Ionel Onet, Pl Fels, Ulrich Lins, Bernard Golden, Ervin Fenyvesi, Vilmos Benczik, Peter Breit, Isrvn Ertl Sr, Ferenc Kovcs, Gyrgy Nanovfszky, Julius Elias and others assisted me in tracking down specific information and in correcting errors. Antonio Ferrer hunted down correspondence in La Laguna. Istvn Ertl Jr, my editor for the new Esperanto edition which I am currently completing, has answered numerous questions, productively raised others, and provided me with suggestions for reading as well as the manuscript of the Esperanto translation of Nina Langlets memoir which he is now preparing for publication. Paul Soros and Flora Fraser have patiently answered my questions and plied me with background information about the family. I am particularly grateful to Simo Milojevi for suggesting that I take this project on in the first place. While many of the accuracies in this volume, to say nothing of the mistakes avoided, are due to people such as these, the errors are mine.

H. T.

Editors Afterword

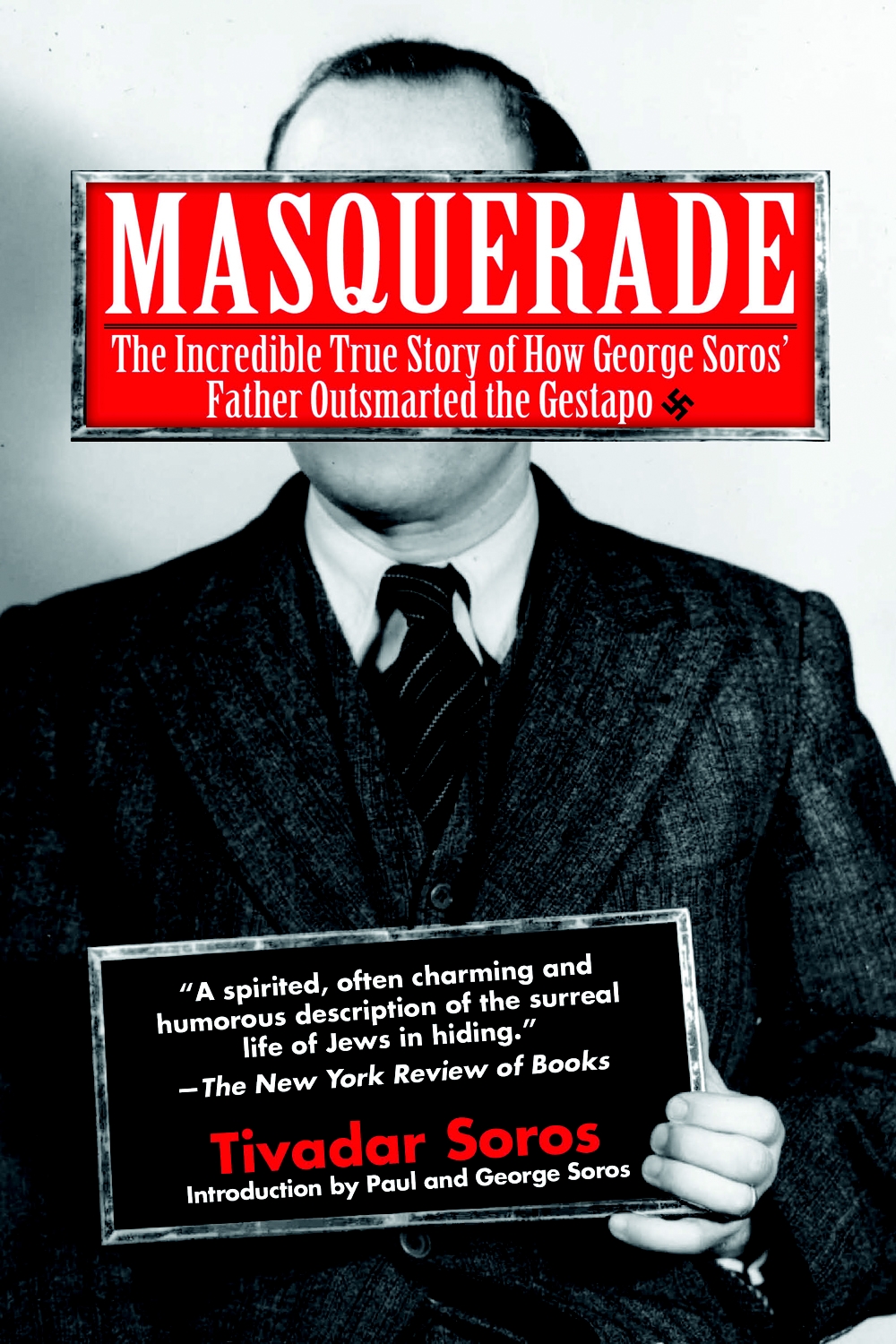

T ivadar Soross powerful influence on his sons is clear: Georges numerous public references to his father and Pauls statements in family memoirs and again in the foreword to the present volume confirm it. Masquerade is the principal public record of that influence a personal history of Budapest under the Nazis and a telling portrait of its author. Tivadar Soros was a charming, exasperating and supremely resourceful individual, for whom a life of adventure in wartime and of discriminating comfort in peacetime was merely a preparation for the test of survival that was thrust on him and his family in 1944 by the arrival of German soldiers on the familiar streets of the city where he had once felt so at home. That was my fathers finest hour, George has written, because he knew how to act. He understood the situation; he realized that the normal rules did not apply... I had a father whom I adored, who was in command of the situation, who knew what to do and who helped others. In short, Tivadar Soros, his insouciant optimism masking a wary and canny protectiveness, was the father every boy dreams of when peril is near. To the 14-year-old George, this time of peril was a great adventure a time when he and his family had to live on their wits in order to survive. Years later, reminiscing about the boys childhood, their mother Elizabeth spoke of their fathers extraordinary love for his children, and of the way in which he never talked down to them, tried always to challenge and encourage them. You see, she recalls her husband saying, I wanted to have them always on my level... I wanted them to understand things as they are. Tivadar had learned the lessons life taught him well, and these lessons helped him and his family survive.

Elizabeths memories, recorded in New York in the 1980s, at about the time she was honored (in her eighties) as the oldest student at Fordham University, bridge two worlds the old and vanished world of middle-class Central Europe between the wars, and the new postwar world of opportunity in America. Her two sons crossed that bridge between the old world and the new, and met success. If Masquerade helps explain their achievement, more importantly it offers a fascinating portrait of a man who found a mission and of the challenges that beset him. As editor of this volume I do not pretend to have a complete understanding of the man called Tivadar Soros, but I do believe that the book reveals those aspects of Tivadars character that he wished to share with posterity, and that the unusual history of its publication offers a story worth telling, both about Tivadar and about the times. Tivadar combined clear and simple values with a willingness to compromise and persuade. He wasted no time fighting battles he knew he could not win, nor in ethical debates where lives were at stake. There is little moralizing in this story, and little hesitancy: only the optimistic urgency of one who felt he had a job to do, a task that he had been given, and who assumed that task gladly and with single-mindedness.

Masquerade focuses on a period of less than a year in Hungarian history, but a year in which hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews, and many other Hungarians besides, were destined to perish. The eleven-month period between the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944 and the liberation of Budapest by the Russians, completed in February 1945 falls into three distinct phases. Hungarys Jewish population had long endured various forms of discrimination, of a kind, sadly, not uncommon in the Central Europe of the day. Hungarian Jews had, over the years, learned to live with such restrictions, and there was a kind of comfortable understanding among all parties that, while the restrictions would not go away, neither would the balance between the classes be seriously upset. Jews had long played a prominent economic role in the country, as financial and industrial leaders. But in the late 1930s, as Hungary moved gradually into the orbit of Germany and as Germany intensified its official anti-Semitism, the balance began to tip: the so-called Jewish Laws pushed the Jews further and further away from the center of political and economic power. Protected by its nominal independence, Hungary for a while was spared the anti-Semitic horrors of Germany and Poland, and other Nazi-occupied territories until March 1944, when the pent-up desire of the leaders of the Final Solution to get their hands on the Jews of Hungary joined with German military reversals in the Balkans and worries about Hungarys loyalty, persuading Hitler to seize power in Hungary. Adolf Eichmann traveled on one of the first trains to arrive in Budapest from Germany, and the Final Solution came with him. Deportations began in late April, and by early July almost half a million Jews more or less the entire Jewish population outside Budapest had been carted off to slaughter.

Eye-witness reports reached the West and resulted in energetic protests by Western and neutral leaders at least considerably more energetic than they had mustered earlier. Although in June the Jews had been herded into so-called Jewish or Yellow-Star Houses scattered across Budapest in preparation for deportation, the Hungarian head of state, Admiral Horthy, felt strong enough to resist Eichmann and his henchmen and was largely successful in halting the planned deportations, at least for the time being. The Germans, needing Hungarian support on the crumbling Eastern Front, did not intervene to reverse Horthys order. So ended the first phase of the eleven-month period, and there followed, from mid-July to mid-October, the second phase: a period of continued outrages, but at least on a lesser scale than before. In late August, Romania switched sides to the Allies, Horthy dismissed his prime minister and brought in a somewhat more moderate government, and Eichmann left Budapest.

A third, horrendous and chaotic phase began in mid-October, when Horthy, in an ill-timed and unprepared move, announced Hungarys withdrawal of support for Germany. Within hours the Germans arrested him and a virulently fascist government was installed in Budapest. As the Russians advanced across the Great Hungarian Plain, an orgy of killing began. Eichmann returned and began organizing forced marches to Austria, fascist gangs roamed the streets, and anarchy descended on the city. It was not until January that the Russians, advancing inexorably across the city, reached the apartment where Tivadar, Paul and George Soros were living, liberating them as Jews but making them spoils of conquest as Hungarians. The city was in ruins. The book ends as the Russians seize control.