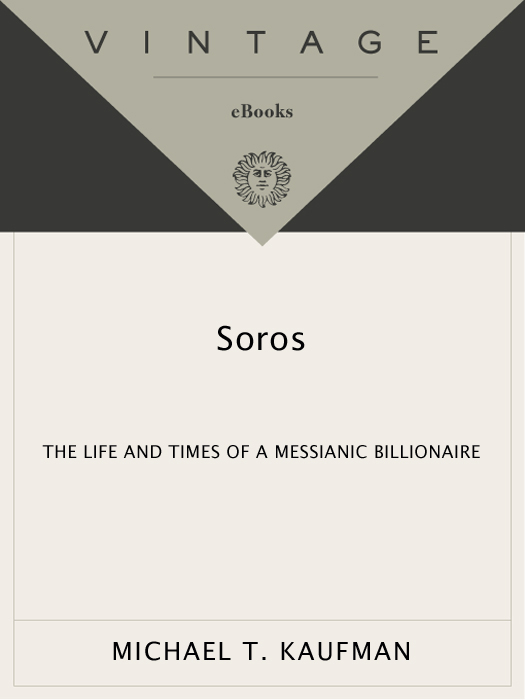

ALSO BY MICHAEL T. KAUFMAN

The Decline and Fall of the Soviet Empire (with Bernard Gwertzman)

The Collapse of Communism (with Bernard Gwertzman)

Mad Dreams, Saving Graces: Poland, a Nation in Conspiracy

In Their Own Good Time

Rooftops and Alleys

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2002 by Michael T. Kaufman

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American

Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by

Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York,

and simultaneously in Canada by Random

House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are

registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

All photographs, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy of George Soros.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kaufman, Michael T.

Soros: The Life and Times of a Messianic Billionaire / Michael T. Kaufman.

p. cm.

1. Soros, George. 2. Capitalists and financiersBiography.

3. Investments. I. Title.

HG172.S63 K38 2001

332.6092dc21 2001032661

[B]

Ebook ISBN9780307765925

www.aaknopf.com

v3.1_r1

For my children, Susan, Seth, and Noah

In practical matters the end is not mere speculative knowledge of what is to be done, but rather the doing of it. It is not enough to know about virtue, then, but we must endeavor to possess it, and to use it, or to take any other steps that may make us good.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

Contents

Introduction

I T IS MY HOPE , as it doubtlessly is with every author, that the story in this book is far better and more compelling than the story of this book. Nonetheless, it seems sensible at the outset to explain how this book came to be written and, more particularly, to describe my relationship to George Soros, the subject of this biography.

Briefly: I had known about Soros and been intrigued by him for more than a decade, when in the spring of 1995 I received a phone call from his Open Society Institute asking whether I would be willing to move to Prague and edit a magazine. The publication, financed by Soros, was called Transitions, and it covered the social, political, and economic transformations then underway in some thirty countries emerging from Communism. At the time of the totally unexpected offer, I was finishing my third year happily writing an unabashedly sentimental column for the New York Times called About New York, which focused on the often remarkable lives of unknown New Yorkers. It was quite a reach to go from that to Transitions, but the people who made the proposal knew that I had covered Eastern Europe for the Times in the mid-eighties and that, as the papers deputy foreign editor from 1989 to 1992, I had helped organize its coverage of Communisms spectacular collapse. They were also aware of a book about Poland I had written in 1988 that had anticipated at least some of the democratic changes that were soon to occur in the dissolving eastern bloc.

In any case, Soross people had their reasons for offering the position to me and I had reasons for accepting. After thirty-eight years with the Times, fourteen of them as a foreign correspondent, I was growing aware that my future at the paper was unlikely to be as interesting as my past and I wanted at least one more adventure. The job itself also seemed challenging and worthwhile: to edit a serious publication dealing with a region undergoing profound, though little understood, changes. In a sense it was like having an opportunity to cover an epoch, like the Reformation or the Enlightenment. And Prague, I knew, was beautiful.

There was, however, another incentive. By taking the job, I would be able to learn a good deal about the Open Societys network of do-gooding enterprises and more particularly about its billionaire founder, George Soros. At the time I had no thoughts of writing about him, though I had come to consider him a fascinating and elusive figure.

My first awareness of him came when I was living in Warsaw. Dissidents throughout Eastern Europe, who were my sources and my friends, were telling me about a mysterious American who was using his own money to support them in their struggles against dictatorial Communism. According to their sketchy accounts, Soros was a wealthy financial speculator who did not welcome publicity about himself or his projects. My friends told me he had been born Jewish in Budapest, where as a boy he had survived the Nazi occupation. Then, after the war, as the Soviets tightened their control over Hungary, Soros, then a teenager, managed to slip under the descending Iron Curtain and make his way to England. There, he studied at the London School of Economics. In the mid-fifties he came to the United States, to begin a career on Wall Street.

I found the few details enticing, and I remember looking up Soros in Whos Who only to discover that he had no listing. But during the next few years I was able to learn a little more about him. He was funneling his money to Solidarity in Poland, to Charta 77 in Czechoslovakia, to dissident groups in Moscow. Later, he opened a foundation in Communist Hungary, and he was providing hundreds of scholarships to bring academics from the East to study and travel in the West.

In 1986 I met Soros briefly, exchanging a handshake with him at a hall in New York where I had been invited to lecture to a group of Hungarian-Americans. They had asked me to elaborate on a story I had written about a secret section of a Budapest cemetery where the remains of several hundred people executed in the anti-Soviet uprising of 1956 lay in unmarked graves. After I flew back to Europe, I learned that Soros had paid for my airfare.

Three years later, I was back in New York on the Times foreign desk tracking the revolutionary events in Europe. By then, though Soross name was still widely unknown, I would hear it mentioned more and more often by those engaged in work on human rights and those monitoring Communisms decay. His Hungarian foundation soon gave rise to others, in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Ukraine, the Baltic, Russia, and the Balkans. He was planning to build an international university. In those days I would sometimes be visited by my former dissident friends who would tell me about playing chess and discussing philosophy with Soros at his summer home on Long Islands Atlantic shore. They described him as a worldly and knowledgeable intellectual who seemed to prefer their company to that of other businessmen.

At the time, Soros was still zealously guarding his privacy. As a financier he had learned to shun publicity, superstitiously fearful that his exposure might jinx the performance of his pace-setting hedge fund, the Quantum Fund. So as he steadily expanded his philanthropic activities, he habitually kept to the shadows, and into the nineties Soros remained largely unrecognized by an American public that could easily identify, and often celebrated, far lesser plutocrats.

All that changed after September 16, 1992, when the British government abandoned its earlier commitment to prop up the value of the pound. Soros was hardly the only speculator to make a fortune on what Britons came to call Black Wednesday, but he was among the biggest winners and he ended up being the one most prominently exposed by the British press. Once his smiling stock photograph looked out at the suddenly poorer readers of the tabloids, the prospect of further anonymity vanished. Besieged by the Fleet Street journalists, Soros decided to talk openly about what he had done, in finance as well as in philanthropy. He made a conscious decision to exploit his new notoriety as The Man Who Broke the Bank of England to gain influence among world leaders and to become what he has since described as a stateless statesman.