ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish I could say I holed myself up in my office with my computer, my books and papers and simply sat down and wrote this book. But like any other author, I needed help and encouragementand a lot of it!

I first heard about the Combahee Ferry Raid about twenty-five years ago. To find anything in those days, before the Internet was so prevalent, meant a trip to a library or lengthy correspondence with someone who might have a bit of information.

About fifteen years ago, the South Carolina Department of Transportation decided to widen U.S. Highway 17 and the bridge over the Combahee River about seven miles from my home. Being that it was in the formative stages of the project, the department had little idea of the historical significance of the area, particularly the bridge and causeway. This caused me to write papers, feed information to newspapers and hold meetings to inform them of the historical importance of the area. While I worked in this endeavor, some historians and friends involved in historic preservation encouraged me to put what I had to paper. So began this book.

One of the first to encourage me was Dr. Stephen R. Wise, noted author, historian and director at the Parris Island Museum. Dr. Wise opened his library and research to me at the museum. Each time he or I would find some little scrap on the raid, we would immediately e-mail or phone the other.

A good friend, Cynthia Porcher, pushed me hard as well. Her interest in womens studies, Harriet Tubman and the Gullah people gave me another perspective. She was also generous in opening her research materials to me.

Valerie Marcil, formerly with the South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, backed me up in my battles with the DOT over a road-widening project at the site of Combahee Ferry and provided with me material from the South Carolina Archives.

Ms. Gary Brightwell of the Colleton County Museum and Dr. Sarah Miller of the Colleton County Historical and Preservation Society both encouraged my work and gave me opportunities to share it in presentations. Gary was also there years earlier in the Colleton County Memorial Library reference room, making sure I had what I needed.

My good friend Bill Olendorf, fellow Trench Nerd, spent countless hours in the field walking over the very land on which the raid took place. I can still hear him calling out for the snakes to move away. He didnt care that they are deaf.

At the National Park Service in Washington is a very unassuming man, a historian, who works from a government-issued cubicle. David Lowe, an author in his own right, is the spiritual leader of the Trench Nerds. Were a group that, for fun, goes into the woods to study mounds of old dirt, Civil War earthworks. David invited me to work with him over the course of a week in identifying Civil War cultural resources and mapping them at the Cumberland Gap National Historic Park. During our time together and at numerous other meetings, David reviewed my work in progress, giving suggestions, editing and encouragingnot to mention going on a few trips to the National Archives and the Library of Congress to pick up a reference or two.

Dr. Phil Shiman is a most enthusiastic teacher and friend who spent countless hours schooling me in the structure of old dirt. Phil confirmed the existence of some of the earthworks at Combahee Ferry.

Thanks to Milton Sernett, whom I have never met but have corresponded with, for his wonderful work on Tubman, and Kate Clifford Larson, who has written probably the finest book on Tubman to date. Her wonderful research on the early life of Tubman fills in many gaps and gives us a complete picture. While she and I differ on the wartime experiences of Tubman, her book fulfills a need in Tubman research.

Congressman James Clyburn showed interest in saving earthworks at Combahee Ferry, be they Confederate or Federal. Thank you for your support with the road project and saving history.

South Carolina representative Reverend Kenneth Hodges encouraged my work and invited me to speak at the dedication of the Harriet Tubman Memorial Bridge over the Combahee River.

I have had the unique privilege to visit numerous plantations involved in the raid in order to research, identify and map the existing earthworks and to understand the lay of the land. Most of the owners and managers do not want to be publically identified, but you know who you are. Thank you for preserving our shared history.

Thanks to my commissioning editor, Chad Rhoad, who put up with my delays, rewrites and questions but never gave up on this project.

Finally, thanks to my wife, Barbara, for her patience over these many years and her unending encouragement to complete this book. Without her, it would not have been finished.

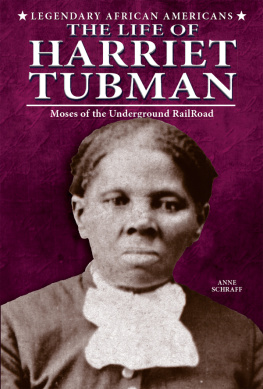

Harriet Tubman. Library of Congress.

INTRODUCTION

With numerous retellings of the story, the Combahee River Raid has evolved into a military action led by Harriet Tubman in which she was a spy, a scout and a commander. Numerous authors have taken artistic license to extol the exploits of Tubman, conveniently ignoring the facts instead of relying on the supposition of twentieth-century authors and the writings of friends in support of a pension application. While they elevate the mythology of Tubman to fit their narrative, they overlook the actions of the eager but ill-trained black soldiers of the Second South Carolina Volunteers. The military tactics of Montgomery and the philosophy of Hunter in raising the regiment are not widely known. Elevating Tubmans stature to military commander of the raid has eclipsed her more important role as a leader of a group of scouts who gathered vital intelligence for Union army headquarters, which is almost universally ignored. There is little in the way of direct documentary sources regarding her wartime activities. Many claims made about her were never acknowledged or described by Tubman herself. So, we are left to piece together her story from the few sources we have.

The raids origins date back to the 1850s and the troubles in Kansas, where, due to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, pro- and antislavery forces went head to head in violent conflict. Out of this maelstrom came men like John Brown, who sought to instigate a slave rebellion, and James Montgomery, a man who shared Browns abolitionist passion. With a civil war looming on the horizon, Colonel David Hunter, a West Point officer, was drawn into the conflict, during which he interacted with Montgomery as his commander and formulated his abolitionist philosophya philosophy forged as much from a desire of command and to ingratiate himself to those he perceived were in a position to further his career. This made him Montgomerys natural ally when war moved from the frontier into South Carolina.