Copyright 2012 by Harold Holzer

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

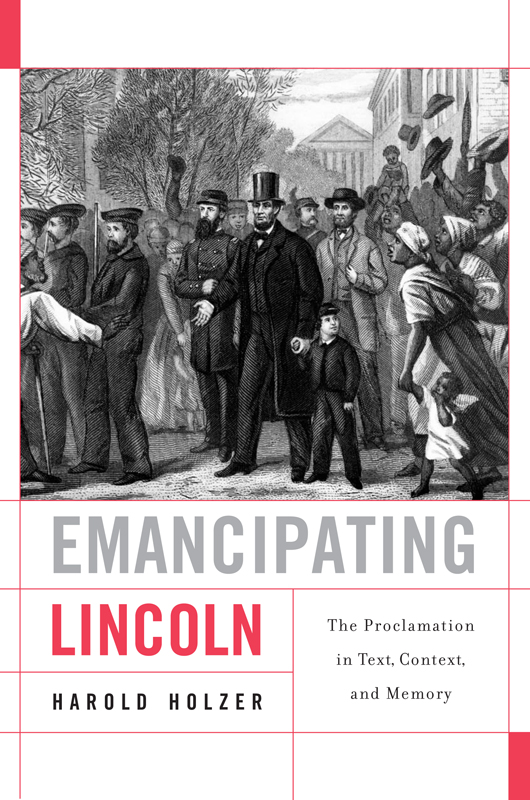

Jacket image: Harold Holzer

Jacket design: Jill Breitbarth

Lincoln Monument: Washington from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes by Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad with David Roessel, Associate Editor, copyright 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., and by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Holzer, Harold.

Emancipating Lincoln : the proclamation in text, context, and memory / Harold Holzer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-06440-9 (alk. paper)

1. United States. President (18611865 : Lincoln). Emancipation Proclamation. 2. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Views on slavery. 3. United StatesPolitics and government18611865. 4. SlavesEmancipationUnited States. I. Title.

E453.H644 2012

973.7'14dc23 2011035161

The world has never had a good definition of the word liberty, Abraham Lincoln confessed more than a year after issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, and the American people, just now, are much in want of one.

The quest for a universally accepted definition has continued ever since. When the Civil War ended in the spring of 1865, the boundaries of American freedom were at least more precisely defined: they restricted the liberty of individual states to depart at will from the American union, and vastly expanded that of African Americans long held in slavery. Yet while history has consistently acknowledged Lincolns leadership in preserving the Union, the credit he once automatically and universally received for accomplishing reunification accompanied by a new birth of freedom has become a matter of disputein fact, increasingly so. Evolving national memoryabetted by generations of vigorous and increasingly harsh revisionist scholarshiphas not been particularly kind to Abraham Lincolns Emancipation Proclamation or his leadership in hastening the destruction of American slavery and with it, the redefinition of American liberty.

A document regarded in its own time with so much trepidation and outright fear that it provoked Wall Street panic, Union troop desertion, bellicose foreign condemnation, vast racial unease, and severe political rebuke from voters at the polls, it is now often viewed not as revolutionary but as delayed, insufficient, and insincere. Its author, condemned for his actions by anxious contemporaries, was later celebrated for and closely identified with the achievement through much of the later nineteenth century by whites and blacks alike, who called Lincoln the Great Emancipator. But that term is now generally considered politically incorrect, and Lincolns entire reputation as an anti-slavery leader has been called repeatedly into question. No wonder revisionists have been debating Lincolns intentionsand with particular emphasis since African Americans achieved their second emancipation in the era of the civil rights movement a century after Lincoln.

Recently Lincoln has come under such intense scrutiny over his purported motives and mysterious timing for emancipation that in some circles he has retreated in reputation from liberator to obstructionist. To his most unforgiving critics, Lincoln was nothing more than a racist who acted on slavery not out of conscience but from desperation. Even as a new generation of scholars renews the debate on the proclamation and its impact, it has become increasingly difficult to discern which oversimplified vision of Lincolns most important act does a greater disservice to history. The question of whether Lincoln was an enthusiastic or reluctant emancipator continues to test our will to understand the complex past as its participants lived it.

This collection does not propose to retreat to the (wisely discarded) grossly oversimplified version of the events of 1862 and 1863, or to substitute a new or revived antique exaggeration for a contemporary one. Though not a narrative history of the Emancipation Proclamation, it proposes to reintroduce authenticity to this crucial discussion by revisiting the document (and its author) at the very moment of its creation and by exploring its impact during the decisive months and years that immediately followed. It attempts to peel away the layers of myth and misunderstanding that have clouded the reputation of both emancipator and emancipation, making it so difficult to discern, much less accept, the proclamations impact in its own time. To refocus the inquiry, it attempts to direct historical attention to the political, military, public relations, and legal realities that Lincoln himself confronted and jugglednot always with perfect successas he attempted to strike a blow against an institution he had reviled all his life but which, until rebellion made its destruction possible, he had concluded he had no constitutional right to challenge.

In recalling Lincolns extraordinary skills as a political strategist, moral voice, peerless prose writer, and ultimately a living and then martyred symbol of freedom, it seeks to revisit the almost incomprehensibly severe pressures under which he labored. It attempts to comprehend the convoluted route he took before he revealed his decision, and to acknowledge the outright disinformation he promulgated, ostensibly to prepare the public for his decision. It will parse the actual words he employed (or rejected) to execute what he himself regarded as the greatest act of his administration, yet maddeningly seemed to craft and announce as if it was routine and unremarkable. And it will trace the evolution of Lincolns own resulting reputation as a liberator, as vivified in words and images alike.

But as this book will argue, modern historians who ill-advisedly apply twenty-first-century mores to a nineteenth-century man are not the only culprits who have made it difficult to see the proclamation within the context of its own time. Lincoln himself is to blame for much of the confusion. He complicated the announcement of his order with such obfuscatory and misleading feints that it is little wonder the public had trouble thenand has continued to have problems ever sincein discerning his true motivations. It was Lincoln who cloaked them in misinformation.

In , these complex diversionary tactics are recalled, set in chronological, military, and political contexts, and reanalyzed, with a special focus on the long-voluble orators frustrating silence during the extended run-up to emancipation. Lincoln may emerge as a preternaturally crafty manipulator of public opinion and the press as he labors to make a truly society-altering order palatable to the widest possible number of Americans. It will no doubt seem reasonable to wonder anew whether he may have vastly underestimated the ability of white Northerners to embrace the notion of black freedomthereby injuring his future reputation for earnestness on the subject of freedom.

As will acknowledge, even when he finally concluded that the timing was right to announce emancipation to the public, Lincoln tamped down its potential status as American gospel by couching his order in uncharacteristically leaden language. Although he privately explained at the time that his goal was to construct a document sturdy enough to withstand future court challenges, Lincoln could easily have introduced or concluded its dry legalese with the kind of soaring rhetoric of which the public knew he was capable. Why he opted to do otherwise in January once he had unleashed the bombshell of the preliminary proclamation the previous September is the subject explored in this chapter. In addition to probing Lincolns creative (or in some cases not-so-creative) impulses, it also asks whether the words that Lincoln later offered in both speeches and public letters to defend and promote emancipation ought to qualify in the historical record as the poetic accompaniment to the prose with which he first announced his proclamation. It is meant to remind readers that while Lincolns January 1, 1863, order was never overturned in law, the jury is still out, the final verdict still due, on the question and limits of his absolute devotion to human freedom.