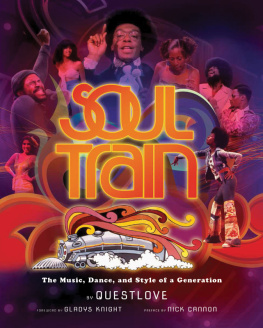

ON FEBRUARY 3, 2012, I got off the subway at Forty-second Street in bustling midtown Manhattan and rolled up toward Duffy Square, a section defined by garish red elevated seats and a glitzy booth where cut-rate tickets for Broadway shows are sold. The New York City police had set up barricades along a section of Broadway, which in the last decade had been converted into a Times Square pedestrian mall. Today this whole area was filled with women and men wearing Afro wigs, long coats, silver platform shoes, round granny glasses, and other flashbacks to fly 1970s gear. The crowdabout a thousand or so folkswas made up of wannabe dancers and cell phonecarrying onlookers. The weather was unusually mild, and that put the attendees in a festive mood, even though we were at a wake for a beloved cultural figure and his iconic television show.

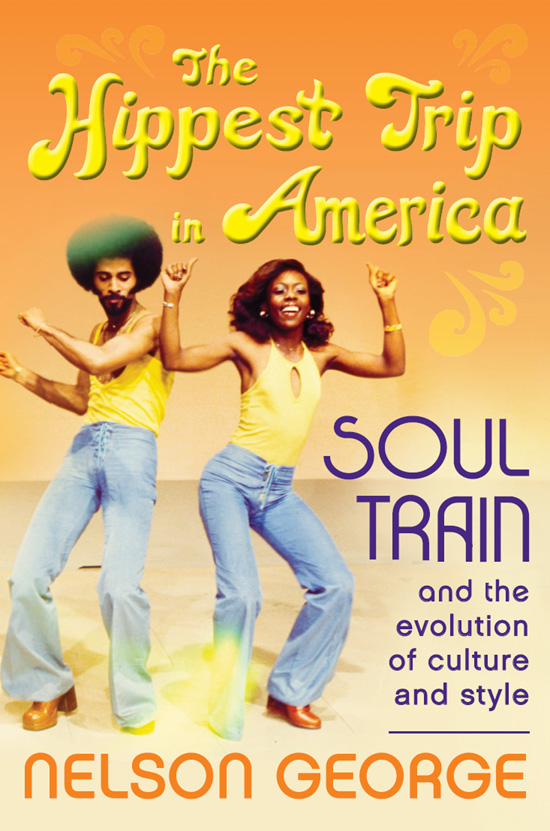

Don Cornelius had died two days earlier. His legacy was strong and undeniable. He had created a television show that ran from October 2, 1971, to March 26, 2006thirty-five years of love, peace, and soul resulting in countless contributions to our collective popular culture. The show was called Soul Train, and Corneliuss death brought about even bigger flash mobs in Soul Train s hometown of Chicago and in Philadelphia, where a Soul Train line was organized that would make the Guinness Book of World Records .

But what the New York gathering lacked in numbers it made up for in enthusiasm. An old-school dancer organized the chaos into a line that ran about a hundred feet. It wasnt as flashy or dynamic as the Soul Train lines you can revisit on YouTube. Nothing done today can recapture that vitality. But the dozens who boogied down the line, and in ad hoc groups around Duffy Square, did so with love and a whole lot of joy.

I didnt dance down the line. Modesty and good sense kept me on the sidelines. But the whole scene did flash me back to many childhood Saturday mornings when my sister and I would sit in front of our familys small color TV and, like thousands of other folks, watch our favorite soul singers and funk bands perform while an amazing crew of dancers gyrated and percolated to the latest hits. The Soul Train line, always near the end of the show, was a highlight. Every show, the dancers would bust out new moves that would be imitated at parties across the country later that night.

On that day in February, we had all gathered to celebrate the life of Don Cornelius, that man with the deep voice and the remarkable wardrobe, who had taken his own life with a shotgun in his Los Angeles home. Though shocked by his suicide, the folks in the New York Soul Train line, as in the lines in Chicago and Philadelphia, werent sober. They had more in common with the exuberant second-line celebrations of New Orleans than anything mournful. Don Cornelius had brought us joy, and it was with joy he was remembered.

Saturday mornings in the 1970s, back in the kitchen of my familys Brooklyn housing project, Id sit alongside my little sister, eat a bowl of Capn Crunch cereal, and watch Soul Train complete with scintillating dancers, soul musics finest performers, and an ultracool hoston our rabbit-ear TV. It was a music show that not only generated hit records but also connected all of black (and a hip section of white, Latino, and Asian) America into a groovy community.

In the pages ahead, youll hear a lot of anecdotes like minetales of Saturday-morning rituals built around the show that, like the insistent rhythm of a great song, will connect you to the joy that was Soul Train s unique combination of music, dance, and personality. These ingredients made Soul Train both one of the longest-running shows in television history and an iconic cultural touchstone for folks not born during its heyday. Somehow Soul Train has soaked into the DNA of our pop culture. The details of its creation, the rituals it embodied for viewers and participants, and the social and media context in which it existed are all part of the story Ill tell.

For casual readers as well as longtime fans, I view this book as a platform for further exploration. Ill mention specific shows and performances with an eye toward inspiring readers to follow up on what intrigues them via YouTube or Soul Train fan sites. The foundation of this book comes from the interviews conducted for VH1s 2010 documentary The Hippest Trip in America, which captured the flavor of the show but, because of time constraints, only used small portions of the interview material.

I interviewed Don Cornelius many times in the 1980s. On my first trip to Los Angeles I flew out from New York to attend the Black Music Association convention. The organization was a well-intentioned attempt to pull together the cultures various branchesrecord labels, radio stations, retail, concert promotion, performersinto a coherent business and social force. While the convention hardly fulfilled its lofty goal and the group has long been defunct, I did get a chance to visit the set of Soul Train. I have vivid memories of DeBarge, the family vocal group from Grand Rapids, Michigan, exiting a van and heading onto a soundstage for a taping. Any glamour Id associated with the tapings was quickly dissipated by the sight of the dancers, most my age or younger (I was twenty-four), looking tired as they impatiently waited for the next act to appear.

When I finally met Don he was cordial, though he didnt go out of his way to make me feel comfortable. I could feel him sizing me up. Was I a possible ally, or a too-smart-for-my-own-good asshole? The lack of outward warmth (a quality often manufactured by Hollywood hustlers on first encounters) stuck out, but so did Dons forthright answers to my questions and his consummate confidence. My memory of that encounter with Don is very similar to the memories of others that youll read throughout the book. Dons bearing, voice, and manner were consistent throughout the years, as well learn from scores of people who spent time with himfrom dancers, musicians, and staff to business partners and friends, from the 1960s until his death. Dons controlled demeanor and unrelenting cool made him hard to know and difficult to get close to, but those who knew him well testify to a funnier, looser man than he revealed to the public.

Don was defined more by his actions than he was by anything he said about himself. Inspired by the civil rights movement, he saw a space for black joy on television. He believed that the music and dance of negroes would be as captivating on the tube as it was in a Chicago house party. He was definitely a race man, but he built professional alliances across racial lines with syndicators, advertisers, and record labels. In the process, he empowered many other black businesspeople while introducing the postcivil rights generation of white consumers to the dynamic power of black music.

As much as Soul Train was Dons show, it was also owned spiritually by the dancers whose creativity and excitement leaped off the TV screen each week. How they got on the show, the moves they made, and the shows effect on their lives are very much the backbone of this story. So many dynamic dancers passed in front of the shows cameras that it would be impossible to capture them all. Only a few are explored in depth here.

So lets go back in time to the tumultuous years of the civil rights movement and the Windy City streets where the hawkknown also as the Chicago windblew hard and long. Pull up the collar on your maxi coat, slide into your platform shoes, and pump that Afro Sheen into your hair.