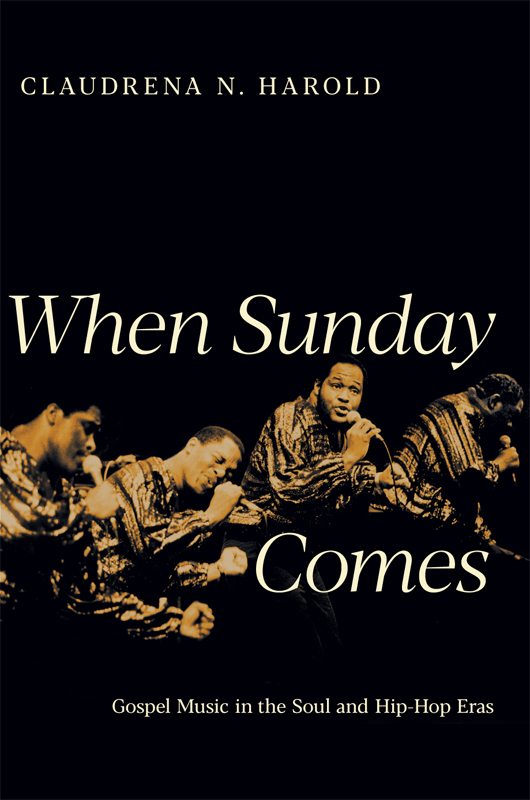

When Sunday Comes

MUSIC IN AMERICAN LIFE

A list of books in the series appears

at the end of this book.

When Sunday

Comes

Gospel Music in the Soul

and Hip-Hop Eras

CLAUDRENA N. HAROLD

2020 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Harold, Claudrena N., author.

Title: When Sunday comes: gospel music in the soul and hip-hop eras / Claudrena N Harold.

Description: Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020. | Series: Music in American life | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020020770 (print) | LCCN 2020020771 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252043574 (cloth) | ISBN 9780252085475 (paperback) | ISBN 9780252052453 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Gospel music20th centuryHistory and criticism. | African AmericansMusicHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML 3187 . H 34 2020 (print) | LCC ML 3187 (ebook) | DDC 782.25/409dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020770

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020771

Contents

Acknowledgments

When Sunday Comes: Gospel Music in the Soul and Hip-Hop Eras is a labor of love. Much of the book was written in the city of Charlottesville, Virginia. In the late spring and summer of 2017, Charlottesville was the site of a series of white supremacist marches that received international attention. In the aftermath of the Unite the Right rallies of August 11 and 12, I agreed to coedit, with my colleague Louis Nelson, Charlottesville 2017, a collection of essays written by University of Virginia (UVA) faculty. That volume examined the legacy of slavery and racial segregation in Charlottesville, situated the controversy over the Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson statues within a larger historical context, explored various First and Second Amendment issues, and sought to provide some answers to the pressing question Where do we go from here? Working on this volume was not an easy task, but it was a manageable one. My earlier work on the Garvey movement had familiarized me with the history of white supremacy in Virginia. And I was quite familiar with UVAs history of racism and the ongoing battle to make the institution a more just and democratic place. Knowing that history proved useful as students returned to campus two weeks after the Unite the Right rallies. Equally helpful was my ongoing work on the history of gospel music, which on many days provided sonic relief. During this hectic time, it was a pleasure to spend hours listening to Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, the Winans, the Hawkins Family, Commissioned, and other gospel favorites. My indebtedness to these and other artists stemmed from much more than the sheer brilliance of their artistry; their theological reflections provided spiritual sustenance as our university grappled with difficult existential and ethical questions. I recall a conversation with an undergraduate entering her first semester at the university. I met her after a forum hosted by the Corcoran Department of History, which sought to historicize recent events. At one of the breakout sessions, this student introduced herself and then relayed her fears about the possibility of the white supremacists following through with their promise/threat to return to Charlottesville in defense of their name, in defense of their cause, and in defense of what they saw as their First and Second Amendment rights. After sharing her concerns, she asked me a question that still lingers with me: How have black people maintained hope given the persistence of white supremacy?

Writing this book has provided me with some answers to her difficult question; so too have the many people and institutions who have supported my work and affirmed its importance. I have benefited immensely from the backing of colleagues in the history department at UVA. I especially appreciate the assistance of the departments staff: Kathleen Miller, Scott Roberts, Kelly Robeson, and Courtney Lazore. Beyond the history department, my colleagues Lawrie Balfour, Bonnie Gordon, Kevin Jerome Everson, Marlon Ross, and Ian Grandison have been extremely supportive of this work. Bonnie and Lawrie have been especially encouraging, and it is hard to imagine completing this book without their friendship, advice, and brilliance.

The same can be said of my comrade Corey D. B. Walker. I have leaned heavily on his critical insights on art, aesthetics, theology, and politics. In addition to offering stimulating conversations, Corey has provided me with challenging yet nurturing spaces to think about these issues. In 2016, for example, he hosted a conference at Winston-Salem State University titled Black Genius, which featured several scholars, including Farah Jasmine Griffin, Greg Carr, Aldon Nielsen, and Steven Thrasher. At that conference, I presented on James Cleveland, shared my concerns about the challenges of biography, and received the affirmation necessary to press forward.

I am very thankful for family, friends, and colleagues who read or engaged parts of the manuscript at various stages: Dave Crawford, Bonnie Gordon, Greg Tate, Yolanda Willis, Andrew Kahrl, John Mason, Dana Cypress, Grace Hale, Lawrie Balfour, Rhon S. Manigault-Bryant, James Manigault-Bryant, Mark Burford, Julian Hayter, Darren Dochuk, Joseph Thompson, Davarian Baldwin, John McGreevy, Daryl Scott, Penny Von Eschen, Kevin Gaines, Reg Jones, and Corey D. B. Walker. I am also thankful to my dear friends Brandi Hughes, Nicole Ivy, Sarah Haley, and Cheryl Hicks, who asked tough questions about the work, my engagement with the artists, and my targeted audience. Another source of support and intellectual rigor has been Jonathan Fenderson, whose work on Hoyt Fuller greatly informed my treatment of gospel music in the 1960s and 1970s. As I wrestled with difficult questions regarding the personal politics of my subjects, I drew heavily on his treatment of Fuller and other figures in the Black Arts movement. The intellectual work and institution-building efforts of my comrade J. T. Roane has also been important in shaping my approach to the politics, theology, and aesthetics of gospel music.

This book has additionally been enhanced by the critical feedback of David Stowe and Robert Marovich. Both of these scholars have had a profound impact on my work. Their suggestions enhanced my analysis of the politics, culture, and business of gospel music, and their attention to tone, narrative structure, and sources enhanced the final product considerably. I am deeply appreciative to the University of Illinois Press for finding such thoughtful and insightful readers. I am especially thankful for the assistance and support of editor Laurie Matheson, as well as for the encouragement of Dawn Durante. And in the final stages of production, Julie Bushs meticulous copyediting made this a much stronger book. Madeleine Molyneaux has been an invaluable source of information as I have navigated the business aspects of the book. Moreover, her support of my collaborative work with Kevin Everson is deeply appreciated. Speaking of Kevin, it is hard to put into words how much he has shaped this book. Over the past five years, he has listened attentively to my perspectives on various gospel artists, most notably James Cleveland and Aretha Franklin; provided valuable suggestions with regard to photography; and helped me make sense of the pregnant silences in the music. More importantly, he has taught me about the power and beauty of collaboration and community. Through Kevin, I have also found a trusted comrade in Kahlil Pedizisai. For several years, Kahlil has provided a sounding board on critical questions and issues in the book and affirmed the importance of the work and my voice. And because of my work in film, I have had the good fortune to discuss music and art with such brilliant minds as Arthur Jafa, Greg de Cuir Jr., Nzingha Kendall, Michael Gillespie, and Cauleen Smith. One of my most important interlocutors has been my cousin Dave Crawford, who always puts me in revisionist mode. I am deeply thankful for his love, care, and intellect.