This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1956 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

REMINISCENCES OF BIG I

By

LIEUT. WILLIAM NATHANIEL WOOD

Monticello Guard, Company A, 19th Virginia Regiment Confederate States of America

Edited by

BELL IRVIN WILEY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

ILLUSTRATIONS

LIEUT. WILLIAM N. WOOD

GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE ON TRAVELLER

GENERAL RICHARD B. GARNETT

GENERAL GEORGE E. PICKETT

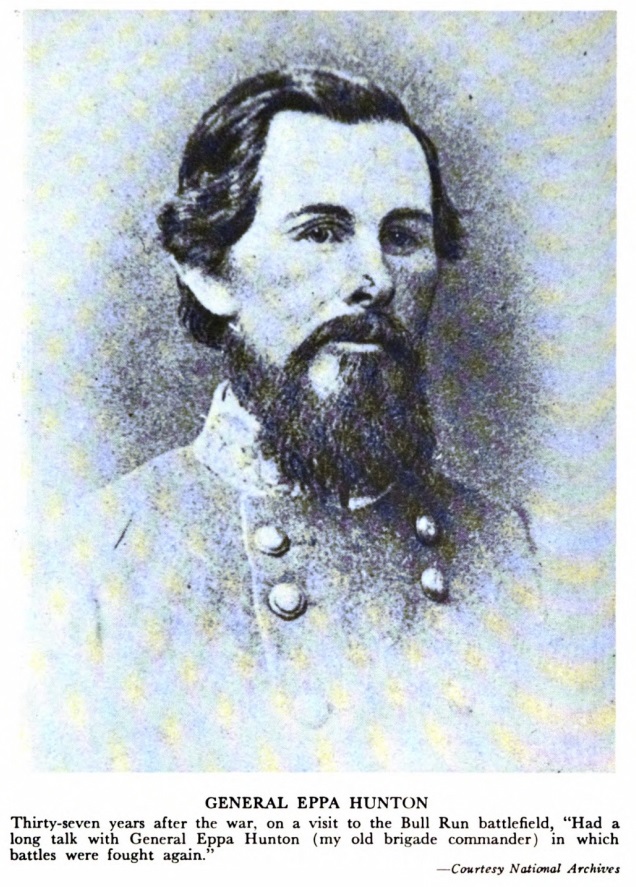

GENERAL EPPA HUNTON

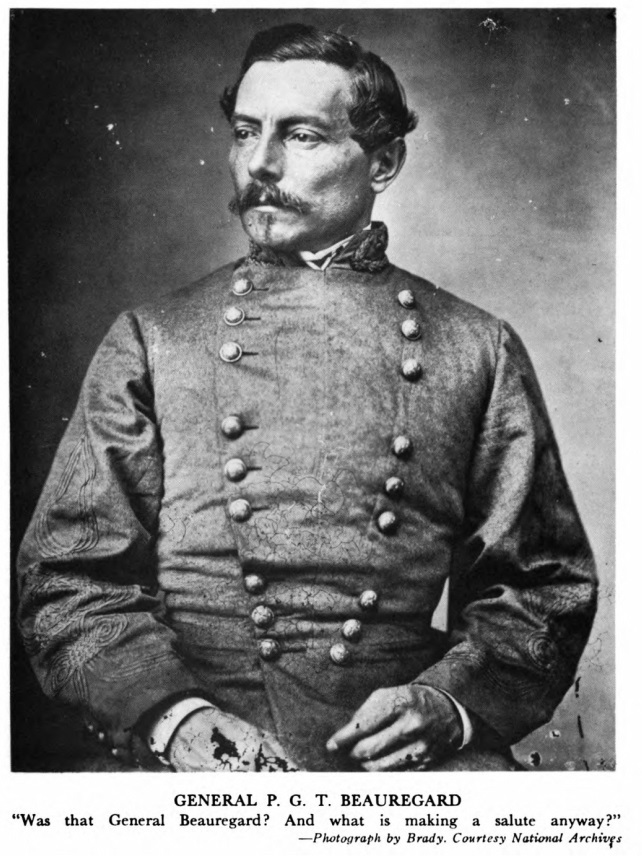

GENERAL P. G. T. BEAUREGARD

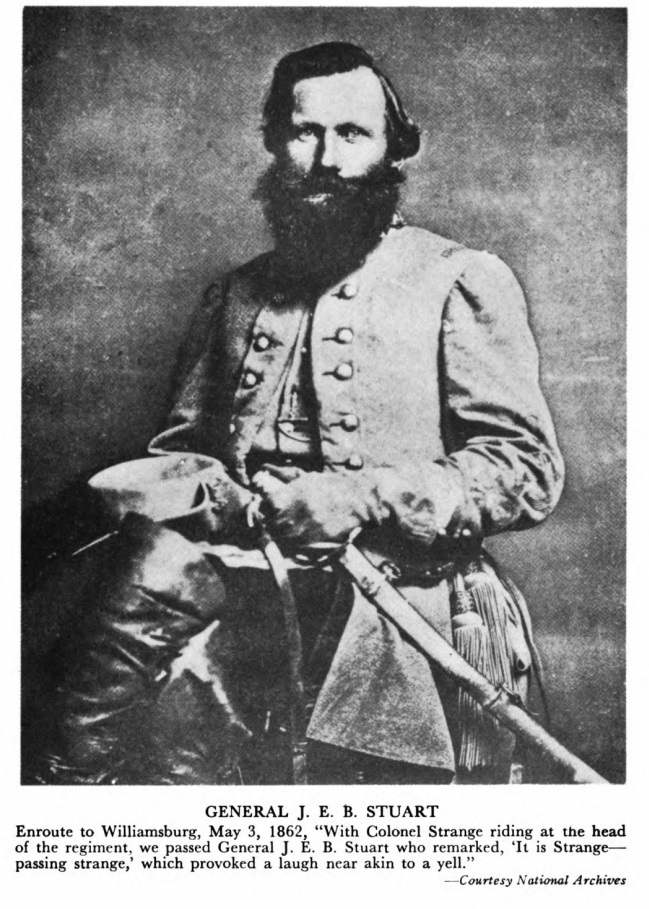

GENERAL J. E. B. STUART

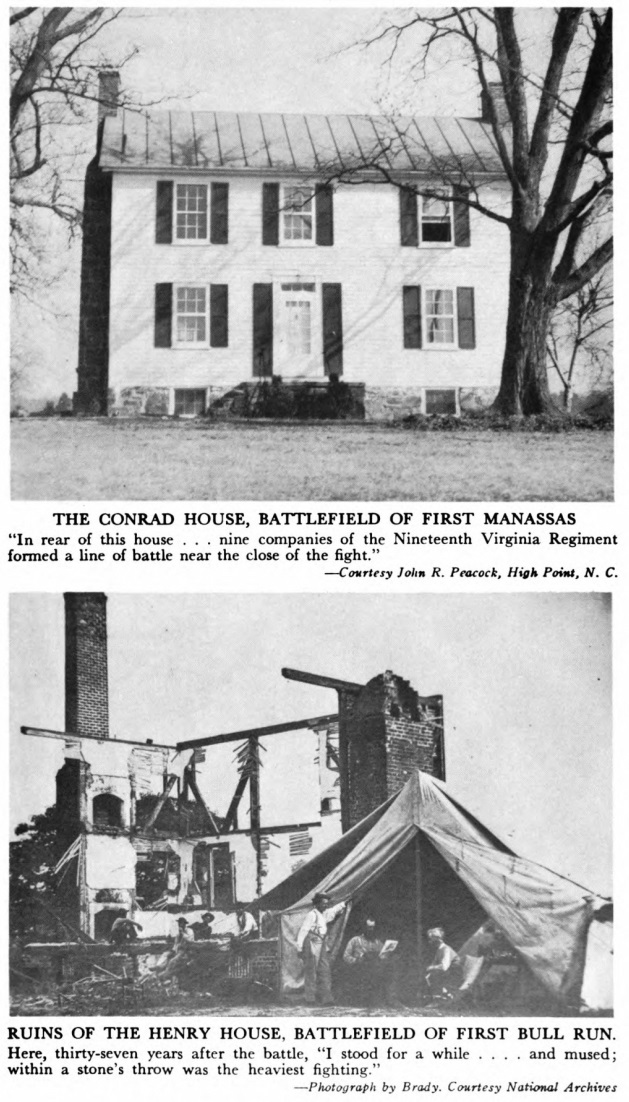

THE CONRAD HOUSE, BATTLEFIELD OF FIRST MANASSAS

RUINS OF THE HENRY HOUSE, BATTLEFIELD OF

FIRST BULL RUN

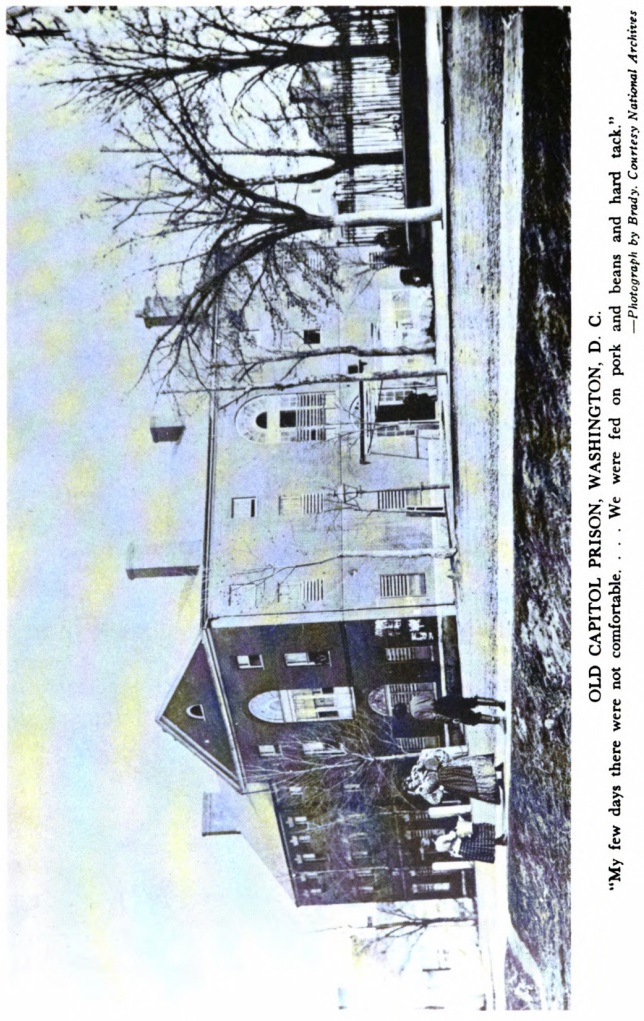

OLD CAPITOL PRISON, WASHINGTON, D. C.

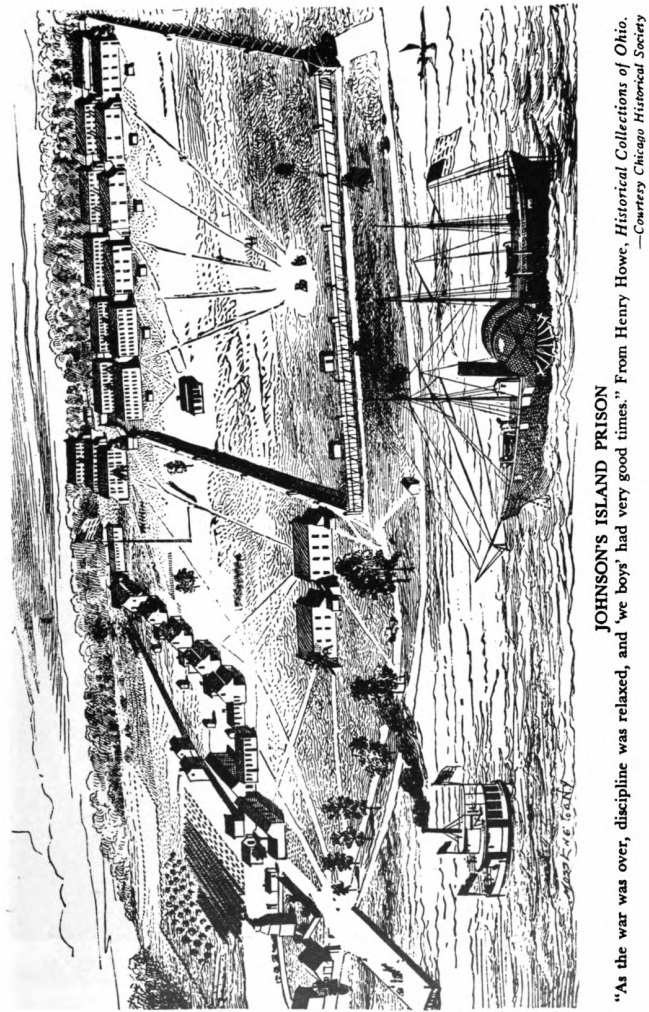

JOHNSONS ISLAND PRISON

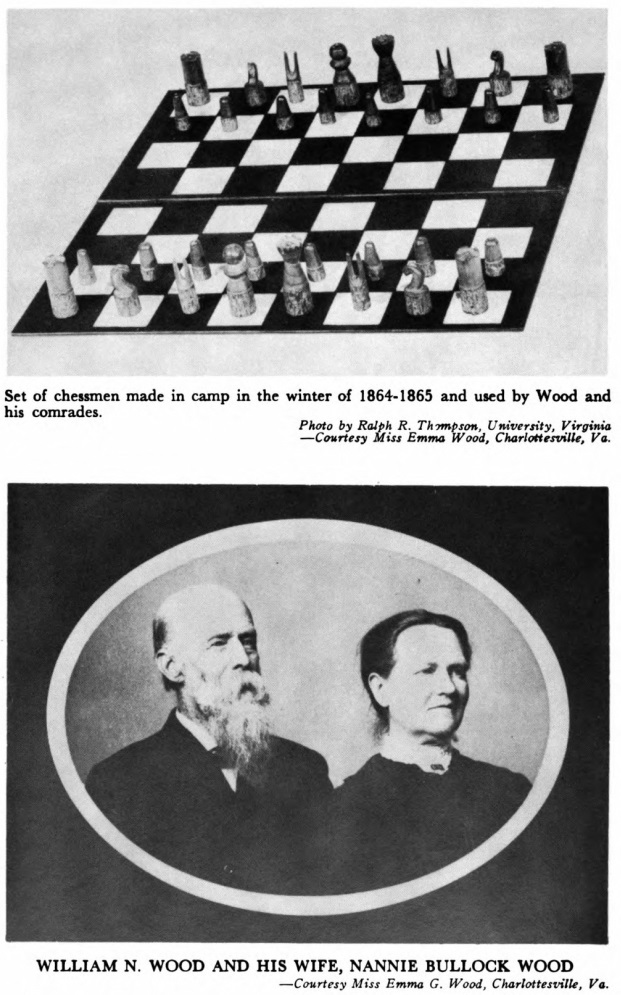

WILLIAM N. WOOD AND HIS WIFE, NANNIE BULLOCK WOOD

INTRODUCTION

Picketts charge at Gettysburg probably has been the theme of more writing than any other action of the Civil War. Common soldiers, nurses, surgeons, journalists, foreign observers, local residents and generals have all recounted their experiences and impressions. But relatively few company commanders who participated in that grand but futile assault have left a record of what they saw and did. Indeed, and especially on the Confederate side, the role of junior officers as told by themselves, constitutes a major gap in Civil War literature. Because of this fact, William Nathaniel Woods reminiscences of Gettysburg and the dozen other major battles in which he participated is of considerably greater value than the usual memoir.

Wood was a lieutenant at Gettysburg and apparently still a shave-tail (though that term seems not to have been current in the Civil War). But he was in command of Company A, Nineteenth Virginia Infantry, in the desperate charge that proved the highwater mark of Confederate arms. When he reached the rock fence atop Cemetery Ridge, after running a gauntlet of fire and lead, he stopped momentarily to survey the situation. His reaction was one of horror. I...felt we were disgraced, he wrote some thirty years later. Where were those who started in the charge? With one single exception I witnessed no cowardice, and yet we had not a skirmish line.

With his foes closing in rapidly about him, Wood did not tarry to ponder his plight, but turned and fled down the slope which he had recently ascended. Bullets peppered his course and riddled his clothing. One ball broke the skin and for a time he thought himself mortally wounded. But examination revealed that the hit was only a scratch.

The scene that he beheld on his retreat accounted for the thinness of the line at the end of the charge. And when on his return to the jump-off point, General Pickett took him by the hand and then turned aside to sob, My brave men! My brave men, Wood felt that after all we were not disgraced. Even so, he was troubled by a lingering disappointment, because, as he put it, We had for the first time, failed to do what we attempted.

William Nathaniel Wood, known by his intimates as Nat, was born near Earlysville, in Albermarle County, Virginia, November 16, 1839. He was one of twelve childreneleven boys and one girlborn to Charles Ezekiel and Martha (Thomas) Wood. Little is known of Williams boyhood, but two letters written while in Confederate service and his war reminiscences indicate that he received a good education, though apparently he did not attend college.

When the war broke out, William, then in his twenty-first year, was working as a clerk in a Charlottesville dry-goods store. His reminiscences state that he joined the army on July 19, 1861, at Manassas, but Confederate records in the National Archives give the place and time of his enlistment as Charlottesville, July 9, 1861. One of his war letters shows that he worked in the store through July 18. Hence, it seems likely that he signed up for service in Charlottesville on July 9 and joined his unit at Manassas on July 19.

Wood began his service as a private in Company A, Nineteenth Virginia Infantry. His company, known as the Monticello Guard, was organized at Charlottesville, and its roster included a number of University of Virginia students.

The Nineteenth Virginia was at First Manassas, but Woods participation was only nominal, as he did not fire a shot during that engagement and he had no soldier equipment except a hat and a musket. A full uniform and the rudiments of drill were acquired after the battle, though Hardees Tactics remained unmastered until the recruit committed the boner of not presenting arms to General Beauregard while on outpost duty, and thus revealed his deficiency to an embarrassed captain.

In the process of becoming soldiers Wood and his comrades informally organized themselves into small groups known as messes. These were composed of about eight men drawn together by ties of congeniality. They ate together, played together, fought together and were welded by common hardships into tight little families that looked unfailingly to their mutual welfare. The members usually acquired nicknames. In Woods mess William Perley, owing to a pronounced inclination of appetite revealed early in the war, was dubbed Frog Legs and Joe Birchhead was known as Beaury after General Beauregard. Sergeant Alexander Hoffmannot in the mess, but a good friend of Woodwas called Pig. If Wood himself acquired a nickname, he does not divulge it. A passage in the reminiscences suggests that his comrades called him Big I, but the manuscript version does not contain this sobriquetwhich seems rather to have originated with Wood after the war.