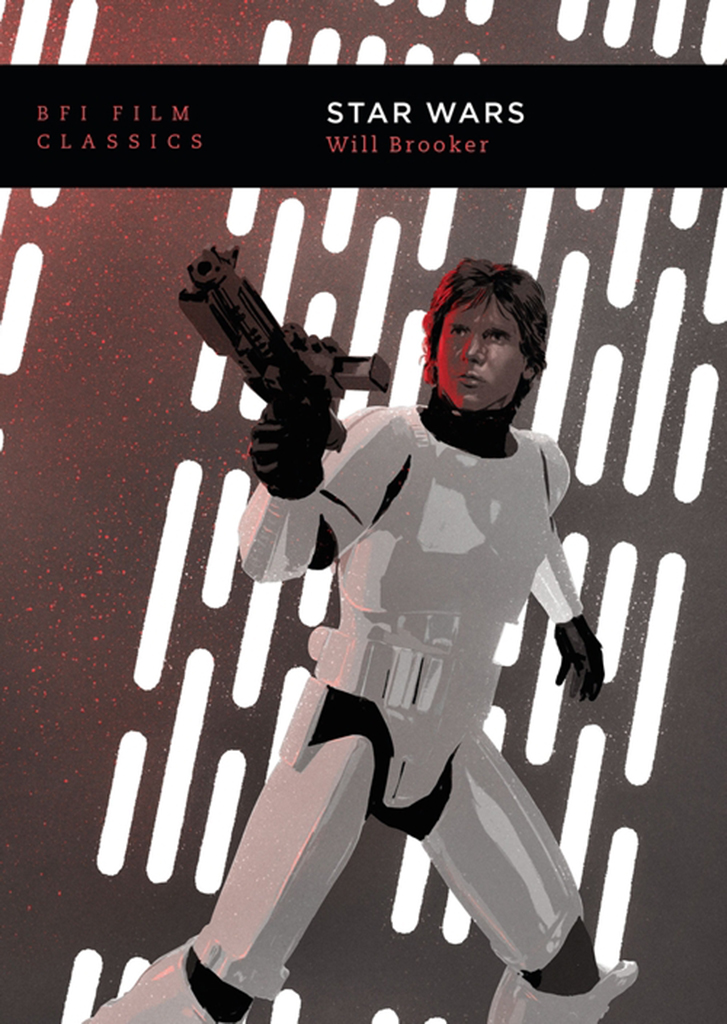

BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visit

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

Contents

Only a Sith deals in absolutes, declares Obi-Wan Kenobi as he faces his apprentice-turned-antagonist, Anakin Skywalker, at the climax of Revenge of the Sith (2005). This critically maligned prequel gives us one of the Star Wars sagas key lines of dialogue, because of the internal contradiction that undermines Obi-Wans bold moral statement and makes it ridiculous: in ascribing that way of thinking only to his enemy, he is of course dealing in reductive absolutes himself.

Binary oppositions structure the three trilogies, echoed visually by recurring, rhyming shots of Tatooines twin suns: Revenge of the Sith ends with Owen and Beru cradling baby Luke under the same binary sunset that he, as a teenager, will gaze at in A New Hope (1977), and the conclusion of the final film, The Rise of Skywalker (2019), shows Rey staring at the same stars.

But those binaries, as this volume demonstrates, are subverted even within the first and supposedly simplest film, as characters pass from one side to the other, their boundary-crossing indicated through details of costume and performance. On a more fundamental level, the official mission of Leias rag-tag rebels is to restore the Republic the system of galactic rule which, the prequel movies subsequently revealed, was complacent and incompetent rather than utopian, and directly enabled the rise of the Empire. Again, the heroes bold certainty Leias dedication to rebuilding the old order is never questioned contains an internal contradiction. What will prevent the process from starting again?

As I suggest in the conclusion, corruption, within Lucass model, does not appear from outside, but festers within. Luke, like Anakin before him, has to struggle not only with external opponents but also with the temptations of his own Dark Side. This fundamental internal conflict, then, operates both on the grand level of Republic and Empire, and on the personal level of the protagonists competing Light and Dark tendencies. But the most glaringly obvious metaphor, central to the first film and recurring in modified forms throughout the saga, is the Death Star, an unbeatable, impenetrable war machine with a single flaw: a tiny exhaust port which, hit at the right angle, will allow a missile to reach the main reactor and destroy the entire space station.

Though the theories of deconstruction associated with Jacques Derrida are never explicitly mentioned in this volume, they seem perfectly suited to its project. Derrida typically aims to unsettle binary oppositions, with the aim not of simply reversing their position but of revealing their interdependency, and he does so by identifying a contradiction at the heart of his target. The seed of a texts deconstruction is already present, a hidden bomb waiting to be triggered. Again, the Death Star provides a perfect metaphor, emphasised by the reveal in Rogue One (2016) that the internal weakness was deliberately inserted by engineer Galen Erso, a secret rebel loyalist within the Imperial system: another slippage between the galactic opponents is, therefore, retroactively placed at the very centre of Star Wars. The Empires most robust structure was always sabotaged, always unstable right from its moment of construction. Nevertheless, the inherently self-destructive cycle continues, not just with the second, incomplete and vulnerable Death Star in Return of the Jedi (1983), but with Starkiller Base in the first sequel, The Force Awakens (2015), whose weak point a thermal oscillator in this case is revealed by Finn, a First Order soldier who defects to the Resistance.

Finns arc, recalling and inverting Han and Lukes infiltration of the Death Star, adds a new dimension to the crossing-boundaries dynamic. The sequel trilogy also complicates the conflict between Dark and Light sides through its introduction of a Force dyad between Rey and Kylo Ren. The promise of his possible redemption is mirrored by visions of her as a villain, while the suggestion of a new path, aligned neither to one side of the Force nor the other, is signified by Reys yellow saber, which transcends the traditional binary between red and blue laser blades.

Yet the broader political aspects of the sequels offer less complexity. The opposing forces are essentially rebranded versions of the Empire and Rebellion, with, it transpires, the same veterans leading them. The First Order is never shown in a position of rebellion against or resistance to the New Republic; when we rejoin the story thirty years after Return of the Jedi, the society Leia fought to restore is already in fragments, and the First Order already an Empire in everything but name, adopting a near-identical aesthetic. For further backstory, we have to look to novels, games and comics, or to the 2019 TV series, The Mandalorian, in which the Empire is splintered into stubborn outposts.

Only one scene, near the centre of Rian Johnsons inventive and subversive The Last Jedi (2017), points to a more interesting structural ambiguity. In the middle of a mission, Finn himself a traitor to the First Order chides independent codebreaker DJ for his cynical opportunism, then tries to reassure himself: At least youre stealing from the bad guys. And helping the good. DJs response is a shrugged, indifferent mumble: Good guys ... bad guys ... made-up words. Hacking a stolen ships data, he muses that the previous owner was an arms dealer. Made his bank selling weapons to the bad guys. Oh! he announces, as Finn glares. And the good.

From their position outside the conflict, the arms dealer, like DJ his nickname stands for dont join can recognise and benefit from the contradictions. Most of the others caught up in this multi-generational galactic war fail to see that the relationship between the opponents is interdependent, and that each side contains elements of the other. Just as the Empire will continue to build more powerful super-weapons with the trigger for their destruction built in, so will whatever brave new republic grows from the First Orders ashes inevitably enable its own demise, and the rise of its enemy. Palpatine calls his revivified armada of Star Destroyers the Final Order, but unless the cycle is successfully deconstructed, the war will never be over: it cant, surely, or the franchise would end.

I have a substantial collection of BFI Film Classics on my bookshelf, their spines arranged in a spectrum of colour, and it is a great privilege to be able to add my own monograph to this prestigious list, alongside the work of authors and scholars I have respected for decades.

My thanks go to those at the BFI and Palgrave who gave me this opportunity: Sarah Watt, who first discussed the proposal, Rebecca Barden, who saw it through, and the anonymous readers who responded both critically making this a better book than it would have been and positively, encouraging me towards its completion.

I am grateful to my friends and colleagues in Film and Television at Kingston University: particularly Frank Whately, who supported my research leave in summer 2008, Abbe Fletcher, for sharing her expertise on Brakhage, and Simon Brown, who led the field in my absence.