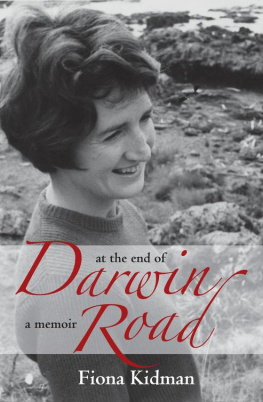

Fiona Kidman - At the End of Darwin Road

Here you can read online Fiona Kidman - At the End of Darwin Road full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Penguin, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:At the End of Darwin Road

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At the End of Darwin Road: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "At the End of Darwin Road" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

At the End of Darwin Road — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "At the End of Darwin Road" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Dedicated to Hugh and Flora Eakin, who lived with me

at the end of Darwin Road

I could not endure to keep so many large classes of facts all floating loose in my mind without some thread of connection to tie them together

Charles Darwin, More Letters

O ver the years I have been accumulating stories about my life in a fragmentary way, through dozens of short essays and articles written for magazines and periodicals. When I reread some of them, I realised that, put together, they began to form a narrative.

Some of my earlier journalism was published in a collection called Palm Prints. By way of introduction, I wrote a clutch of personal essays, ending them at my twenty-third birthday, when I had just become a mother and was starting to think of myself as a writer. At the time, I decided that was as far as I wanted to explore my life in public. But I have changed my mind. To be a woman writing in this country for forty-five years has been a mixed experience, but one I decided I wanted to tell people about, after all. Besides that, my life as a writer has yielded me the good fortune of meeting some fascinating people. You have only one life to draw on. Those who have read Palm Prints may find some of the early chapters in this book familiar but different, too.

My year in Menton, as the 2006 Meridian Energy Katherine Mansfield Fellow, offered me a unique opportunity to view my life from a distance, perhaps more so than if I had written about it here in New Zealand, to see myself more as a character and, more importantly perhaps, to see others as characters. At heart, I remain a novelist.

A few names have been changed or abbreviated. None of this alters the main narrative. There are quite enough recognisable people in it as it is.

This is the first of two books that give an account of my life.

Fiona Kidman

2007

L ast summer I went north to Kerikeri, where I lived when I was a child, after the end of the Second World War. I drove along Darwin Road to the patch of land my parents once owned. As I looked beyond the luxuriant tropical growth of the orchards, towards the stand of blue gum trees in the distance that formed the boundary, I heard voices of the past reaching out to me. I was overwhelmed with such a feeling of loss, and yet such a vivid sensation of memory, of the exact way things were in that odd little place, and how they shaped me as a person, that I turned away. This is all too much, I said to myself. This will be the last time I come here.

For much of my early life, I grew up surrounded by the sharp citric scent of orange groves, bright heat and, however curiously detached, the shadow of Asia. Kerikeri is a small town, so different from the rest of New Zealand, that it astonishes me how few people are aware of its post-missionary story. They see the Old Stone Store, which symbolises New Zealands early colonial history, and the rich new town centre, in stark contrast to other less prosperous towns in the North, but nothing of what came in between: the ideal city, which a group of expatriate British people who had been stationed in the Far East set out to establish in the 1920s. They came, bristling with military titles, laden with jade and precious artefacts from China, and built their houses. Some of them were little more than shacks in the dust; a few of them were grand and based on Oriental influences. Around them, they planted citrus trees and passion fruit, shaded by rapidly growing belts of gum trees and red-tipped hakea hedges. The ones who had money found servants, by one means or another.

It was to one of the larger houses that my family first moved. My father had gone ahead to find a place for my mother and me to stay while he worked on a house for us on land he had bought from one of the earlier settlers. My mother thought we would be paying board and lodgings. Much to her surprise, she discovered, on the night of her arrival, that she was to be the cook.

Thus began my life as the servants girl, at least until my father had fashioned a home out of a converted army hut on the piece of land he had bought at the end of Darwin Road. Some of that story forms the basis of my early novel called Mandarin Summer. A later short fiction, called All the Way to Summer, explores my life in the town.

There have been times when I have wanted to put all of this behind me. Like the day I went up Darwin Road and stood looking back towards the trees. On the spot where I stood, a green wooden gate once hung between strainer posts and a wire fence. The words Goathland Farm were painted on the gate in white letters.

What for you call your place Goatland? one of the Dalmatian men of the neighbourhood once asked my father. (The Dalmatian gum diggers had arrived before the orchardists.) My father tried in vain to explain that it was Goathland, named for some place in Yorkshire dear to his heart. But of course thats what our place did become known as Goatland.

That evening, I lay in the dark in the Abilene Motel, which is down and along the road a bit, and listened to summer rain on the roof, and heard the rustle of gum trees, and it occurred to me that however many times I left Kerikeri, the place would never leave me. Of course I would go back. And I did, but its surprising how things can change in a very short time. A few weeks ago, before I left New Zealand, I went north again, and the gum trees had gone.

I am writing this story of mine from Menton, in the South of France, where I am in residence as the Katherine Mansfield Fellow. This honour, bestowed annually, allows a New Zealand writer to live in Menton and work at Villa Isola Bella, where Katherine Mansfield lived in 1920, and wrote a number of her most renowned short stories. In just three years she would be dead from tuberculosis, at the age of thirty-four. I have come here in the springtime, with my husband Ian Kidman. We live in an apartment block on a hill called Monte du Lutetia. Our apartment is shabbily genteel, with large rooms, red tiled floors, rickety white French furniture, and three balconies facing down avenue de Verdun towards the Mediterranean Sea. This town is famous for its citrus. Beneath us stands a large grove of orange trees that are just being harvested for their late crop; the streets are full of windfalls. And the air is full of the dizzying perfume of new citrus blossom; when I walk down the streets I feel as if I have been drinking quantities of Cointreau, the scent is so intense. Its like being in Crete in the springtime: you come down from the mountains into warm sun-filled valleys, and you are overpowered and languidly drowsy from its impact. Or in Kerikeri when I was a child.

If it was Mansfield who brought me to this French sojourn, it was a variety of French writers who first drew my interest towards France. Marguerite Duras, a writer I have long admired, was one. I remember hearing her on the South Bank Show she died in 1992 saying that what has happened to us by the time we are sixteen or so is what will shape our impressions of the world for ever after. In essence, I think she is right, even if the age is somewhat arbitrary it depends on what kind of a person you are, what you have already learnt about the world. I had known of Duras since I was a young woman myself when I saw her film Hiroshima Mon Amour, the devastation of love among the ruins, the way a shadow on a mans back makes a woman both momentarily forget barbarism, and embrace it. Not long after that, I began to read her novels about growing up young and illicitly in love in Vietnam. You would have to be French to write like that, I thought. Since then, I have followed the path of Durass girlhood through the teeming oleander-lined streets of Ho Chi Minh City, as it is now, although hardly anybody calls it that; to those who know the city, it will always be Saigon. I have sailed along the vast coffee-brown waters of the Mekong River, on leaky barges with canopies to protect travellers from the sun, Durass novels clutched in my travel bag, and understood how that early landscape, and what happened to her there, might have shaped the way she lived her life. However various her invention, the heat, the river, the violence and the sensuousness of a liaison behind Saigons shuttered windows lie behind every literary decision she made. She did not say that we cannot change, or learn, or perceive the world from different angles. But there, lying at the heart of us, is the unshakeable truth of how we were made.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «At the End of Darwin Road»

Look at similar books to At the End of Darwin Road. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book At the End of Darwin Road and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.