Foreword

BY FIONA KIDMAN

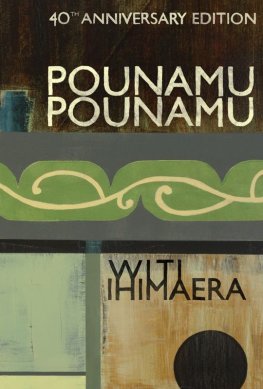

Witi Ihimaeras 1972 collection of stories, Pounamu Pounamu, changed the face of literature in Aotearoa New Zealand, paving the way for what would later be known as the Maori Renaissance, an unprecedented flowering and recognition of Maori arts and literature in the 1970s. Over the years, Witi has described these early stories as a response to Bill Pearsons essay, The Maori and Literature 19381965 (in Erik Schwimmer (ed.), The Maori People in the Nineteen-Sixties: A Symposium, 1968). In his essay, Pearson had commented on the absence of published fiction by Maori writers, and noted that our literature lacked the perspective of Maori experience. With the publication of Pounamu Pounamu, all of this changed. A rural Maori community and the day-to-day lives of its inhabitants form the cornerstone of the stories, and readers were enchanted. The book long ago achieved the status of a platinum bestseller (determined when a book has sold more than 50,000 copies in New Zealand), as have other subsequent books of Witis. Millions of words must have been written about the author and the publication of Pounamu Pounamu. My account is more personal than critical, a record of that time when Witi published his ground-breaking collection, and we had the mutual good fortune to develop a lasting friendship.

Witi and I met in Wellington early in the spring of 1970. At the time, he was working by day as a journalist at the Post Office and writing in the weekends. Our paths had crossed fleetingly more than once, and certainly we had shared space in the periodical Te Ao Hou and in the Listener, where Witis first stories appeared. We were both protgs of a splendid old BBC character, Arthur Jones, who was a script editor in the drama department of what was then the New Zealand Broadcasting Service. It was at a scriptwriting seminar organised by the drama department that we got to know each other. Ours was an instant friendship. Witi has frequently reminded me of the way I was dressed that day: white knee-high boots, a miniskirt and a leather cap. It was enough to catch his attention and he teased me mercilessly as a latter-day Mod. Although there are only four years difference in our ages, he looked to me like a merry teenager and I kept telling him he should be in school. By the end of that day, we had laughed at a great number of things, and at each other. The day didnt stop after the doors shut behind us, and we found ourselves sitting on the edge of the street, still talking. None of this or the conversation we had about where we came from seemed in any way forced or artificial. I had grown up in the North, immersed for periods of my schooling in classes that were predominantly Maori. We felt like a couple of country kids who had hit the Big Smoke. I hadnt felt so alive or joyful since I arrived in the city earlier that year.

What else did we talk about that afternoon? Well, we shared dreams of becoming real writers, and we both felt we had many things to write about. Witi loved the movies. He wanted to follow the yellow brick road and indeed, the symbol of the Emerald City from The Wizard of Oz had already begun to appear in his stories. When at last we parted company, he said, I reckon were hitched to the same star, you and me.

And, as his books began to appear far sooner than mine, as it happened he wrote above his autograph in each one a variation of the phrase, we are still hitched to the same star. To one, he added the phrase for better or worse. Indeed, we have shared the ups and downs of our vocation, and supported each other as best we could, never further than a letter or phone call away.

Our friendship deepened over the year that followed that first meeting, as we visited back and forth at Witi and his wife Janes Hungerford Road house, overlooking Wellingtons wild south coast, and at our place in Hataitai. Jane was Pakeha, and my husband Ian is of Maori descent. Our experiences of mixed marriage in the 1960s and early 1970s were acknowledged, but I cant remember that we ever dwelt on it. On the professional front, Witi and I were both encouraged by Robin Dudding, editor of Christchurch-based Landfall, who was opening up that journals pages to less established writers than his predecessor, Charles Brasch, had, including the voices of women writers and multicultural writers.

Witi and Jane were hungry for overseas experience before they settled to having children. In the following year, when they were in London, Witi wrote in intense bursts, a habit he has followed throughout his career. By the time he returned, he had written the balance of the