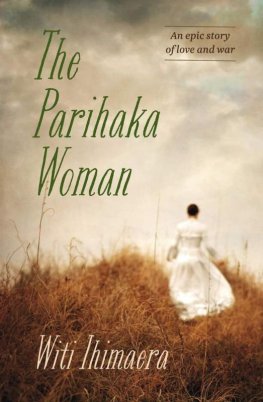

In deference to Taranaki iwi, the magnificent Taranaki dialect is used throughout the novel. Some spellings and word usage will therefore strike some readers as unusual, for example, mounga rather than the standard maunga, and tauheke for old men rather than the standard koroua. As well, because Taranaki Maori do not sound the h, this usage has been marked with a single apostrophe, e.g. aere instead of haere, mii instead of mihi and taueke instead of tauheke.

Taranaki Maori pronounce the wh as in whare not as an f sound but rather as a soft wh as in the English word whine. This usage is also marked with a single apostrophe, e.g. ware.

The exception to the above is that names, such as Te Whiti o Rongomai, Tohu Kaakahi, Parihaka, Horitana and so on, are not marked in this manner. Please note that these names would be pronounced as Te Witi o Rongomai, Tou Kaakai, Pariaka and oritana. In fact in some nineteenth-century manuscripts Te Whiti and Parihaka are rendered as Te Witi and Pariaka.

A further exception is that where quotes have been taken from other sources and commentaries, the quotes are as rendered by the original authors.

1.

Im a retired high school teacher who once taught history, and Im not important.

I was born in the Taranaki and so was my wife, Josie, whom I met in the 1960s. In those days, if you were a young bloke like me, you got drunk after playing rugby with your mates and hoped youd meet some nice girl at the pub. Thats where Josie caught my eye. She was out painting the town red with some of her girlfriends, though she likes to change that story now and tells people we met at the local Sunday school picnic. Yeah, right.

Josie and I got married and, a few years later, bought our three-bedroom bungalow here in New Plymouth. We honeymooned in Australia and, since then, weve had a trip to London and another one to Hong Kong to see New Zealand play at the Rugby Sevens. Weve lived in New Plymouth all our lives, and have three children and seven mokopuna. Josies saving up to take them to Disneyland.

As for the bungalow, well, we bought it for the view of Taranaki Mountain. New Plymouth at that time was a small town with oil rigs off the coast. Look at it now: prosperous port, tourism, an art gallery, even a mall. A lot of the original outlook has gone as other houses have mushroomed around us but we still have a great view from the sitting room, and the bathroom too, if you open the window when youre sitting on the lav.

Doesnt the mountain look majestic today? When Captain Cook saw it in January 1770 he thought he had naming rights and called it Mount Egmont; apparently there was an Earl of Egmont and, for all I know, Cook might have known him.

To Maori, of course, the mounga has always been Taranaki. Geologically speaking, its a volcano, dormant right now, and it is very sacred to us. People have taken to calling it The Shining Mountain, which is how it looks in winter when it is snow-capped, but also in summer the peak sometimes glistens. Forgive me if I boast, but can you see how perfectly shaped it is? Its symmetry is similar to that of Mount Fujiyama in Japan, and I guess thats why Tom Cruise made his movie, The Last Samurai, here in the Taranaki. Josie got a part as an extra, but I was offended that somebody would borrow our mountain and pretend it was someone elses.

The mounga has always been ours.

Of course Taranaki is more than a mountain. It is a tipuna, an ancestor. Born in a mythical past when mounga were able to move, Taranaki had an unhappy love affair with another volcano, Pihanga, and shifted west to get over it; the Whanganui River now pours along the deep channel scored in the earth by Taranakis passing.

Taranaki lived through amazing historical times. How did the mountain feel, I wonder, when, some seventy years after Captain Cook, it saw European ships bearing settlers from across the sea? Im talking about the early 1840s, when English migrants from Great Britain bought inland bush country from Taranaki and Ngati Awa tribes, and six ships of the Plymouth Company arrived to settle it. Between 1841 and 1843 around 1,000 settlers raised New Plymouth.

By 1859, however, the migrants wanted more land. They cast their eyes to the north-west: if they purchased land there, they could have a harbour.

Thats when the troubles with the Maori, here in the Taranaki, started.

From the very beginning, the purchase of what became known as the 600-acre Waitara Block was disputed, and Wiremu Kingi Te Rangitake refused to let government surveyors onto it. I have no desire for evil, he protested, but, on the contrary, have great love for the Europeans and Maoris. Although there were such verbal objections from Maori, no violence was offered. One contemporary newspaper account relates, instead, that the surveyors were ignominiously overcome by one aged kuia who embraced a member of their party, and another woman who removed a protective chain.

This provocation was apparently enough, however, for the government troops to fire on Te Rangitakes pa at Te Kohia, on 17 March 1860. The defenders withdrew, but soon retaliated with warrior reinforcements from as far south as Waitotara. Although the Crown had the greater firepower, and the battle had a disastrous impact in terms of the number of chiefs who were killed, Te Rangitake rallied and was victorious at the battle of Waireka thirteen days later. The great chief Wiremu Kingi Moki Te Matakatea, already renowned for years of fighting, sided with him. His name, which meant The Clear-Eyed One, referred to his lethal marksmanship.

Humiliation is a good word, I think, to describe how the government troops must have felt, but the Pakeha exacted their revenge the next day. They had a warship, the Niger, off the coast of Taranaki, and the captain was ordered to punish the Maori victors. Not by direct bombardment of the rebel force, though; no, by targeting the Maori settlement at Warea in the kind of lateral and indirect retaliation on civilians for which they were to become famous.

Warea was a small, tranquil village led by Paora Kukutai and Aperahama Te Reke. It had also become the home of two remarkable young chiefs, Te Whiti o Rongomai and his uncle, Tohu Kaakahi, and their band of followers. Some twenty years earlier they had returned to the region from Waikanae, further south. Te Whiti was baptised by Minarapa Te Rangihatuake a Maori missionary who had migrated with them and from the beginning Te Whiti was marked for leadership.

Minarapa set about raising a Wesleyan church and pa at Rahotu. In addition, by agreement of Te Whiti and Tohu, a mission station was established at Warea by the Reformed German Lutheran missionary, Johann Friedrich Riemenschneider, otherwise known as Rimene. It was there that Erenora, the Parihaka woman, was born. At the time of the bombing, she was four years old.

When she was an old woman in her eighties, Erenora told of the terror of the occasion in an unpublished manuscript thats lodged in Anglican Church archives at St Johns Theological College in Auckland. As it was written in Maori, it has been overlooked and forgotten, but it is from this document that we, her descendants, have been able to access the information that is contained in this narrative.