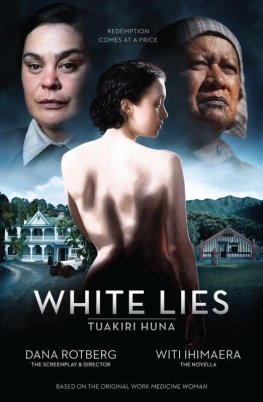

White Lies

The Novella

by

Witi Ihimaera

For John Barnett, who persists in putting New Zealand stories on screen.

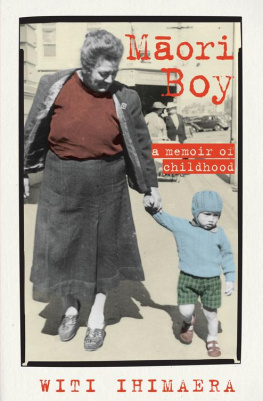

WITI IHIMAERA

In 2007, I received a call from Rosa Bosch, a friend of mine in London. Rosa, an effervescent, incredibly well-connected film sales agent, had worked with us in bringing Whale Rider to the international market. Her expertise in the Hispanic/Latin American market is legendary. She knows every player and all the talent new and established. She told me that a friend of hers, Dana Rotberg, a film director who had been a leading light in the Mexican film industry in the early nineties, had now moved to New Zealand, and we should meet.

One reason that Rosa felt we should meet was to do with Danas motivation for coming here. Dana and her daughter, Rina, had been living in a small town in Mexico, and by chance they had gone to see Whale Rider. The next day, as Rosa told it, Dana decided to move to New Zealand, and, sure enough, here she was, living fifteen minutes away.

Dana and I met and I asked what she wanted to do creatively. She told me she wanted to settle into New Zealand and be a mother to Rina. We talked more, and I said that if she found a project she would like to direct, Id be happy to assist.

In late 2007, Dana invited me to a party she was having for her father, who was visiting from Mexico. I took her a book of Witis short stories, Ask the Posts of the House. Some months later, Dana told me that she had found a project and that it was the novella Medicine Woman, which was one of the stories in Ask the Posts.

Dana took the novella and, in changing and adapting the roles and motivations and the inner qualities of the characters, the film story became a triangle of confronted and conflicting identities.

White Lies, the film version of Medicine Woman, would be quite different from the other films I have made. But one theme that captured me was identity, and thats something I am interested in. I am interested in how people assert their identity, how they claim it, why they reject it and the consequences of their actions. And I feel that across most nations, cultures, religions, the same elements hold true.

So, for me, White Lies is about three characters who are all at different compass points in their connection to their identity: Paraiti, whose beliefs and daily practice are absolutely shaped by her culture; Maraea, who has turned her back on her heritage, culture and people; and Rebecca, who has no knowledge at all of where she comes from. And this triangle is one which has universal resonance.

That was what determined my decision to work with Dana and to adapt Witis work into the film. Witi tells stories that are universal in their themes and specific in their setting. That approach enables them to reach audiences beyond those who are the subject of his writing.

As we develop our sense of our New Zealandness, we often struggle with issues of ownership of ideas, and there are some who feel that Witis works, written by a Maori author, mostly set in Maori communities, can only be told by Maori. I do not hold with that any more than I think that only a Scotsman could write Macbeth, or a Moor could write Othello, or a Jew The Merchant of Venice. Our world culture is enhanced by the ideas we ingest from all the experiences we have. When one looks at Roman, Greek, Norse or Polynesian mythologies, we see that each culture has a number of gods whose functions are evident in all the other cultures. The emotions that drive people, their actions and reactions are universal, and that also gives us the connection to seemingly different worlds.

I felt Dana would bring a filter to the adaptation of Medicine Woman which would be quite different to that which a local filmmaker might bring. Her experiences in Mexico, and in the Balkans, would give her a take on identity that might make the film accessible beyond the shores of New Zealand. She would tell it from the outside in, rather than the inside out.

And, as with Whale Rider, Witi agreed.

So we began the process of adaptation and the eventual production of White Lies.

Film production is a journey that often requires the travellers to adapt to circumstances as they change around them. The script and the schedule and the best-laid plans evolve as the production takes place the exigencies of location, weather, performances, budget and myriad other elements all impact on the process, and the script changes as it moves through the production. The script that is published here is the script of the film that has been delivered and released in cinemas.

As mentioned before, Danas script and the film were based on Witis original novella Medicine Woman. But just as a film script is a living, breathing entity, so a novel can also change and adapt, and Witi has rewritten the story in his own way, adding scenes, expanding the background and putting in elements in readiness for the sequel he plans to write one day. So, while the original novella is reproduced at the end of this book, what we are showcasing here is how a story can take on new lives, and evolve in different media, with alternative endings and emphases. This book is a celebration of Witi and Dana, and of that creative process.

I am thrilled to say that I think the film Dana has made has realised the aspirations I had for this powerful story.

John Barnett

Producer

I acknowledge with gratitude all those who made the film White Lies Tuakiri Huna possible (in chronological order):

BOBE TERE-TERESA GOLDSMIT BRINDIS: I made this film in memory of the tears I saw you shed, longing for the true colour of your soul.

RINA KENOVI, my daughter: Because you are the one who inspires me to be a woman of honour and always follow my heart and my dreams. Because in your eyes I find the reason and the purpose for working hard, with honesty, bravery and truth, so we can make a better world for all. For your solidarity, your patience, your always pragmatic advice and for forgiving my absence from your life during the last two years. For helping me translate, revise and correct the many pages I have written for this project from Spanish, my language, to English, your new language.

NIKI CARO: For changing my life with your film Whale Rider. Your vision was a profound mirror to the soul of the people and the land. A vision that inspired me to leave Mexico, my homeland, in search of a new life for me and my daughter on this group of tiny and remote islands at the extreme end of the Pacific Ocean: Aotearoa New Zealand.

JIM BUTTERWORTH: For saving my life the first winter I spent in this country, and taking me to hospital in time so I wouldnt die. For being my Kiwi father and my best friend.

ROSA BOSCH and SHEILA WHITAKER: For believing that my voice as a filmmaker was still alive, no matter for how many years it had been silent. And for working hard so we can all see this film fly high.

JOHN BARNETT: You took the risk and believed in me, a total stranger with an explosive temperament. And you produced this film, an extreme challenge for all of us, and the most sacred experience I have ever had as filmmaker. I thank you forever.

WITI IHIMAERA: For your Medicine Woman, a most beautiful gift.

JON ARVIDSON: For helping me with the English grammar and translation of the synopsis of the script and Characters Journey document.

Next page