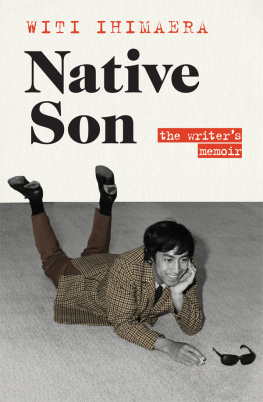

Witi Ihimaera - Native Son

Here you can read online Witi Ihimaera - Native Son full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Penguin Random House New Zealand, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Native Son

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Random House New Zealand

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Native Son: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Native Son" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Native Son — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Native Son" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This is the second volume of memoir by this remarkable writer and of the living myths that inspired him at the beginning of his career.

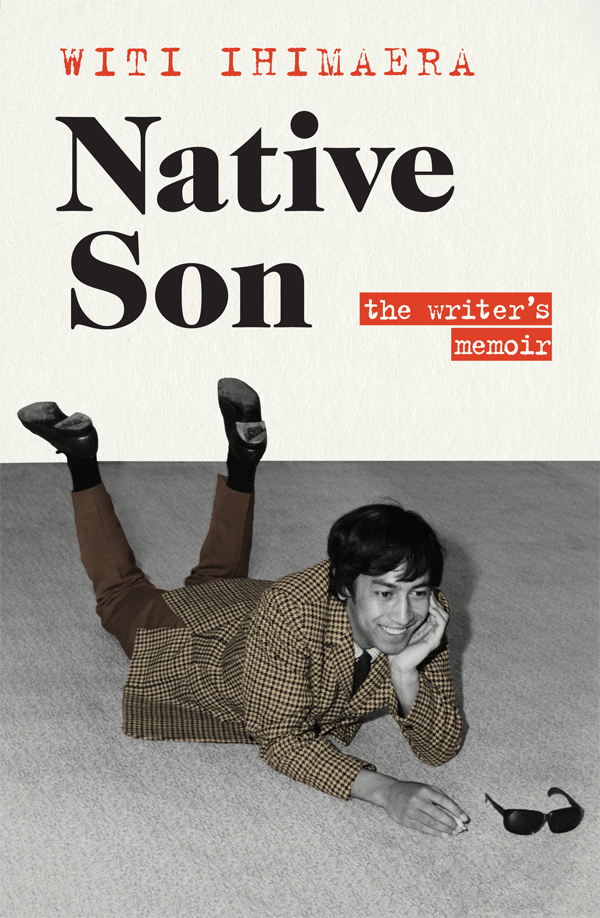

Look at him, the young man on the front cover. The year is 1972, he is twenty-eight, his first book is about to be published, and he has every reason to kick up his heels.

But behind that joyful smile, and the image of a Mori writer footing it in the Pkeh world, there is another narrative, one that Witi has not told before. The story of a native son, struggling to find a place, a voice and an identity, and to put a secret past to rest.

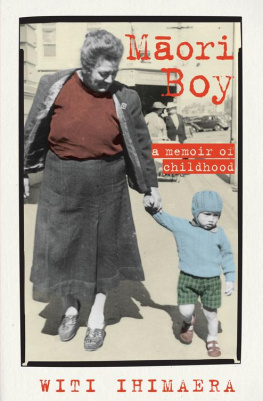

This sequel to his award-winning memoir picks up where Mori Boy stopped, following Witi through his triumphs and failures at school and university, to experimenting sexually, searching for love and purpose and to becoming our first Mori novelist. It continues in the same vein as the first volume, which was described by a reviewer as a rich, powerful, multi-layered and totally unique story something every New Zealander should read.

Witi Ihimaeras first volume of memoir, Mori Boy: a memoir of childhood, won the general non-fiction section of the 2015 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. He edited, with Tina Makereti, Black Marks on the White Page and published the novella Sleeps Standing/Moet (te reo translation by Hmi Kelly), both in 2017. Sleeps Standing/Moet was the first te reo/English novel published in New Zealand. In 2019, Ihimaera edited, with Whiti Hereaka, Prkau: Mori Myths Retold by Mori Writers. It was his twelfth edited work of New Zealand and Mori literature, an unparalleled witnessing of a peoples literature since they began writing in English. A full list of Ihimaeras publications prior to 2015, and his biography to that year, can be found in Mori Boy: a memoir of childhood.

A hard-working writer, Ihimaera premiered his fourth opera, Flowing Water, composed by Janet Jennings, at the Hamilton Garden Festival 2018. He was the writer and presenter of In Foreign Fields (John Kier, Wena Harawira, Mike Jonathan), a television documentary screened on Mori Television, Easter 2018. It was his David Attenborough moment, which saw him visiting and filming Commonwealth War Graves during a two-week schedule in Singapore, England, Israel, Tunisia and Turkey (Gallipoli).

Witi Ihimaera was the recipient of a Chevalier des Arts et Lettres in advance of Bastille Day in 2017. In the same year he was awarded the Prime Ministers Award for fiction. He was the New Zealand Writer of Honour at the Auckland Writers Festival, 2018. Since 2015 he has represented New Zealand literature at festivals in Bhutan, India, China, Taiwan, Canada, New Caledonia and England.

He is the patron and a trustee of Kotahi Rau Pukapuka, a foundation committed to publishing a hundred national and international books into Mori.

For my grandfather

A Glimpse Through the Literary Whakapapa

The mentors, I never forgot you

CHILDHOOD

Teria Pere, Mini & George Tupara, Tilly Tupara, Winiata Smiler, Mafeking Smiler, Mary and Hape Rauna, Hani Smiler, Miss Hossack, Mr Grono, Mrs Cole, Sister Wortley, Brother Murphy, Bulla, Charlie and Blossom Mohi

LITERARY WHAKAPAPA

Julia Keelan and Te Haa o Rhia Ihimaera Smiler Jnr, Pei Te Hurinui Jones, Bruce Mason, Arthur Jones, Nicholas Zisserman, Noel and Kiriwai Hilliard, Joy Stevenson, Kterina Mataira, Arapera Blank, Bill Pearson, Barry Mitcalfe, Ian Kidman, Maurice Shadbolt, Robin Dudding, Te Aomamaka Jones and Pax Jones

ACADEMIA

Bruce Biggs, Ranginui Walker, John Rangihau, Bill Parker, Koro Dewes, Judith Binney, Dorothy Crozier, James Bertram

GISBORNE HERALD

Ted Dumbleton, Jack Jones, Percy Muir, May Gillies, Jean Colebrook

POST OFFICE

Fred Leighton, Tom Martindale, Paul Katene

FOREIGN AFFAIRS

Frank Corner, Ken Piddington

THE WIND BENEATH MY WINGS

Ray Richards

AND MY GRANDFATHER

Pera Punahmoa

N reira koutou kua riro ki te P, ka maumahara tonu au ki a koutou. Kia rtou, kia koutou, kia ttou, tn koutou, tn koutou, tn koutou katoa.

of all the genres, memoir leads us down more unexpected paths than any other. We think we know ourselves, but do we really?

Fiona Kidman to author,

6 January 2018

To understand my story, you must listen to the myths of my world, the myths that I was told as a child, more potent and real to me than any Greek or Roman legend. They fed my imagination, shaped my perspective and pointed a way forward.

There is also another myth in my life, the one I told myself about myself.

I created it to avoid telling the real story.

Witi Ihimaera

At the end of 1959, aged fifteen, I sat School Certificate. I required two hundred marks from four subjects to pass, and thats what I managed. One mark less, and my life might have been entirely different.

The pass may have been the minimum, but as my headmaster Jack Allen said to Dad, shaking his hand vigorously as if he didnt quite believe it, Congratulations, Tom, well done. Not my hand, Dads.

Youd think Dad sat the examination, I said to my mother, Julia, as yet another local, queueing up, slapped him on the back.

Good on you, Tom, he said.

At that time, Te Karaka District High School was a rural school, which, looking back from the present, existed on the faraway edge of the decile, but a pass was a pass no matter how hopeless the hri or hick the town. Fifth-form School Certificate was as high as you could go as there was no sixth form. Anyway, that would be pushing your luck. Therefore, despite the usual ambitions I had in common with other boys, such as becoming a jet fighter pilot (we did have one in the family, my uncle Baden), my reality was that I would leave school and help Dad on the farm like Keith and David Wright on the landholding next to ours.

To be frank, although I had not taken to agricultural work as to the manner born, I was fond of farming. I dont know why as there was nothing romantic about working the land. Season after season, doing the same repetitive work. Buying the cheapest stock and hoping that cattle grown on sparse grass would bring maximum gain at the annual sales. In summer, mustering the sheep to move from one paddock to the other. Watching cattle dying in times of drought, that was hard to bear. Or losing lambs even after wed pulled them out of their mothers. Wed blow into their nostrils to help them breathe the chill air only to feel the slight shiver in their bodies, the sign of impending death.

Then there were the usual chores that my sisters and I had to do before we caught the school bus. We were up at five to light the fire, get the stove going and lay the table for breakfast. My sisters Kararaina, Twhi and Viki squabbled over who would take our baby brother Derek from his cradle, change his nappy and feed him. Meanwhile, morning and night, I shared milking, chopping wood, the occasional slaughtering of an animal for its mutton, and other heavier farm duties with my cousins Ivan, Miini, Kiki, Tom and Uenuku (Banana). And when we returned home from school in the afternoons, there were always other jobs to do: fencing, boiling offal for the dogs, daubing maggot-infested sheep with tar or tending the vegetable garden. Sometimes we did the work under instruction from Dad, Uncle and the grizzled old farmhand, Bulla, who had turned up one day looking for work and stayed. The three men were weaning us from their care, waiting for us to do the tasks whether they did or didnt ask for them to be done.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Native Son»

Look at similar books to Native Son. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Native Son and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.