Mark Barnhouse - Lost Denver

Here you can read online Mark Barnhouse - Lost Denver full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Arcadia, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

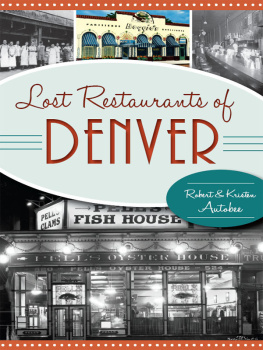

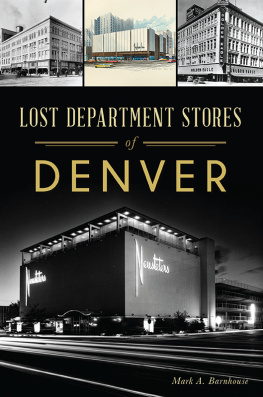

- Book:Lost Denver

- Author:

- Publisher:Arcadia

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lost Denver: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lost Denver" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lost Denver — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Lost Denver" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

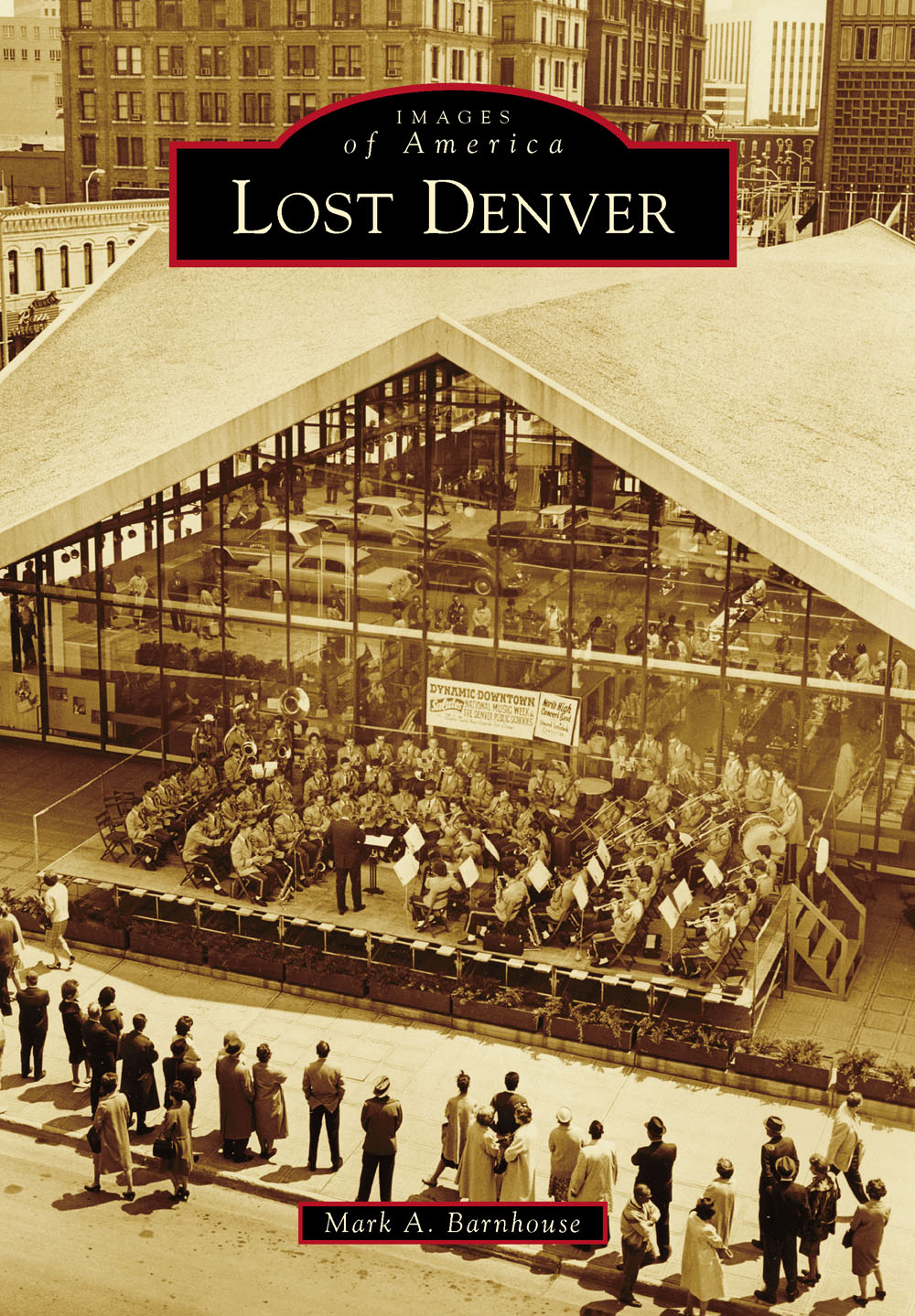

IMAGES

of America

LOST DENVER

DEMOLITION PROTEST, 1990. When the elegant Jules Jacques Benoit Benedictdesigned Central Bank and Trust Company faced demolition (see ), historical preservationists rallied, unsuccessfully, to save the building. These protesters carry signs with a vintage photograph of the building (by Louis Charles McClure, an important early 20th-century Denver photographer), a testament to the importance of historic images to an appreciation of Denvers history. (Roger Whitacre collection.)

ON THE COVER: MAY-D&F, 1965: The pride of downtown, the glass-walled concrete hyperbolic paraboloid structure in front of the May-D&F department store became an instant landmark when it opened in 1958. Here, it backdrops a lunchtime concert by the North High School Concert Band. It was demolished in 1996, despite many Denver citizens hopes for its preservation. (Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.)

IMAGES

of America

LOST DENVER

Mark A. Barnhouse

Copyright 2015 by Mark A. Barnhouse

ISBN 978-1-4671-3291-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439652770

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015941077

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Matt Wallington, who helps me remember

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

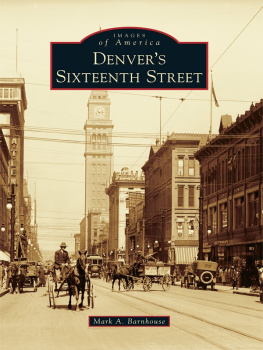

The author is enormously grateful to the following individuals who have been so kind as to lend photographs, postcards, and other items from their collections, who have made it possible to meet someone else who had something unique to contribute to this work, or who have made valuable suggestions: David Forsyth, Joanne Goble, Matt and Leslie Krupa, Sarah O. McCarthy, Dave Metcalfe, Rob Mohr, Dr. Thomas J. Noel, Bob Rhodes, Suzanne Ryan, Shantelle Stephens, Izzy Vera, and Roger Whitacre. Denver is blessed with wonderful archives staffed by helpful professionals; the author thanks Coi Drummond-Gehrig, digital image collection administrator at the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, and Melissa VanOtterloo, photograph research and permissions librarian at the Stephen H. Hart Library of History Colorado, along with many other helpful staff members at both institutions. Many thanks also go to my title manager at Arcadia Publishing, Stacia Bannerman, and the Arcadia production team. The late James Bretz encouraged me to continue writing books, and I thank him posthumously. Most especially, thanks go the readers of my earlier Arcadia volumes, Denvers Sixteenth Street and Northwest Denver, who have told me about things that they remember and inspired me to write this book.

The images in this volume appear courtesy of the Denver Public Library (DPL), the City and County of Denvers 19091930 magazine generally known as Denver Municipal Facts (DMF), History Colorado (HC), various individuals (as noted), and the author.

INTRODUCTION

Denver, the Mile High City, has existed only since 1858, making it younger than most other American cities of comparable size. Its economy has cycled through numerous booms and busts. During booms, each new generation of city builders has sought to make its mark, assuming its works would endure for decades, if not centuries. Each subsequent generation, however, has wiped away, in some later boom, the legacy of those who came before, in the never-ending quest to remake the city.

Some changes have been natural, even necessary. If they are to thrive, cities must evolve as they attract new residents and new technologies develop. Certainly, no Denverite would want to return to unpaved manure-filled streets, nor would any sensible person want to preserve in amber every unpleasant aspect of todays Denver. But likewise, no thoughtful resident would want to erase the past entirely in favor of a Denver filled only with generic new buildings, no different from anyplace else.

The idea that we might want to preserve some important pieces of our past is not new. Denvers first historical preservationist was Margaret Tobin Brown (known posthumously, but never while she was living, as Molly Brown). In 1927, when the former home of Denver journalist and poet Eugene Field was threatened with demolition, she bought it, and later paid to move it to Washington Park, where it stands today. In 19321933, architect Jules Jacques Benoit Benedict sought ways to adaptively reuse the old Denver County Courthouse, a grand, if outgrown, 1883 edifice occupying a full block downtown at Sixteenth Street and Court Place. He proposed a museum, a permanent exhibition of Colorado products, and other functions. It was to no avail; the penny-pinching administration of Mayor George Begole, having just moved into the then new city and county building, wanted the courthouse either sold or demolished. Since there were no buyers with that much ready money during the Great Depression, down it came.

Then came World War II, followed by a new generation of city builders, encouraged by youthful mayor James Quigg Newton. Anxious to cement Denvers status as an important city, these men (and they were all men) sold key downtown landmarks to any developer willing to give the city a dynamic, modern skyline. On Capitol Hill and in other historic neighborhoods, developers razed mansions built by 19th-century gold and silver barons, often replacing them with parking lots or cheaply built apartments. Following the lead of other cities, Denver created the Denver Urban Renewal Authority (DURA), which facilitated new opportunities for private developers downtown, and which, ignoring the wishes of many of their residents, rid the city of whole neighborhoods it deemed blighted slums (what was then called Lower Downtown, centered on Larimer, Lawrence and Arapahoe Streets, and Auraria, just southwest of downtown, being the most prominent examples). A great many people at the time approved of DURAs efforts; at the urging of Mayor Thomas Currigan, Denver voters handily passed DURAs Skyline/Lower Downtown renewal plan in 1967.

Some did not approve. Modern-day historic preservation in Denver was born in the 1960s, as thoughtful residents feared that too much was being lost, and future generations would lack a connection with the citys past. The city-chartered Denver Landmarks Commission was formed in 1967 and initially led by Helen Millett Arndt; she and the commission immediately got to work, attempting, mostly unsuccessfully, to convince DURA not to tear down key buildings in its Skyline project area. About the same time, and for a similar reason, a savvy woman named Dana Crawford formed a partnership to purchase most of the buildings on the 1400 block of Larimer Street and convinced DURA to leave them standing; the result was Larimer Square, today a popular dining and shopping destination. Then, galvanized by the destruction of so many irreplaceable historic buildings, the nonprofit foundation Historic Denver, Inc. was born in 1970. Its first major project was the purchase, renovation, and opening as a museum the then threatened home of Denvers first preservationist, Molly Brown. In the years since, it has pursued other projects, pioneered the use of easements to give old buildings second lives, and continued to advocate for endangered historic structures all over the city.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Lost Denver»

Look at similar books to Lost Denver. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Lost Denver and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.