Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Robert Autobee and Kristen Autobee

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.239.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014953329

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.715.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to recognize and thank everyone who spoke to us in the course of this project. Their enthusiasm and thoughtfulness remind us that food is often the first course of building friendships. The encouraging words, helpful suggestions, time, and expertise of the librarians, archivists, and curators at the Denver Public Library, Western History Department, and History Colorado were invaluable. We appreciate the comments and perspectives of Dr. M. Frisbee and Dr. L. Lohman.

We also wish to remember Robert and Ruth Mohr for their kindness and hospitality that live on in their sons and grandchildren.

Finally, special thanks to our mothers and fathers, who showed us what silverware to use and taught us to always thank our host when invited out for a meal.

Introduction

A city is more than its architecture or its sports teams. It is what its residents cook and eat. In a time when most conversations revolve around two topicswhat people saw on television the night before and what they recently atedining keeps us in touch with others and gives a community its character. Now and in the past.

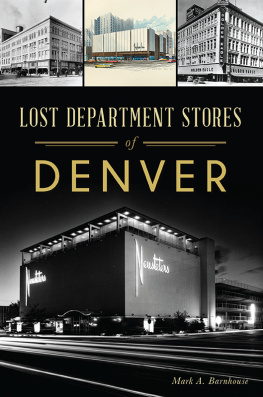

The ground rules for this dining history of Denver are brief. This story is of Denvers lost restaurants through the owners, the clientele, and the food they served. We hope that this will include a warm memory of a good meal or two. But why did we write about a restaurant that lasted only a few years in an off-the-track neighborhood, while a long-standing institution receives barely a mention? Allow us to say the following: the buffet was too big. This volume acknowledges some of the citys heralded restaurants while recognizing the trends, groups, and special dishes not discussed in previous examinations of this subject.

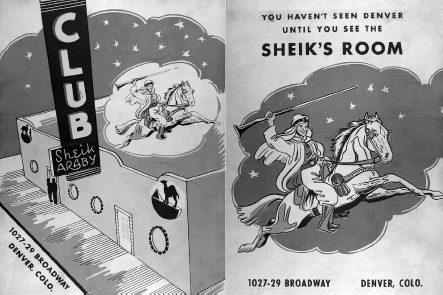

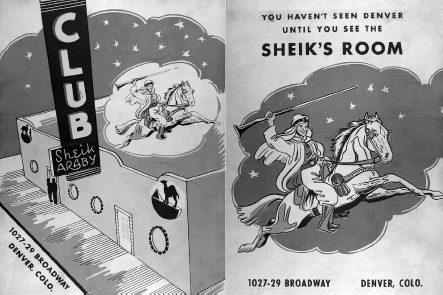

The number of restaurants recalled by and to the authors was staggering. How many Denverites remember the Club Sheik Araby on 1027 Broadway; the Organ Grinder on Alameda; Valentes on West 38th Avenue in Wheat Ridge; Grandpas Hamburger Haven, also on West 38th; the Holly West; the Peppermill; the Gemini; Wuthering Heights; Cocos; Little Pepinas; the revolving restaurant on the top floor of the Holiday Inn overlooking Colorado Boulevard; Baby Does Matchless Mine; Mattie Silks; the Bay Wolf; or the Rocky Mountain Diner?

It wasnt the Thief of Broadway, but the Club Sheik Araby is one of thousands of Denver restaurants from the past 150 years. From Menu Collection, WH1509, Western History Collection, Denver Public Library.

Congratulations are in order for Patsys Inn in north Denver for being a few years short of a century. The Fort in Morrison has championed late owner Sam Arnolds vision of Wild West cooking for more than fifty years. Now forty, Casa Bonita shows no signs of waving the white sopapilla flag of surrender. We wish we had space to tell the story of the El Rancho in Evergreen or Eddie Bohns Pig n Whistle on East Colfax in Denver. Each place rememberedor forgottenno doubt had stories deserving of a multivolume set.

This history of the Mile High City through its restaurants is a story of red sauce restaurants in north Denver, Mexican combination plates served out of peoples kitchens, African Americans denied service by the citys established restaurants, and partnerships formed between ethnic groups that celebrated being alive through delicious food. It is also the story of an isolated yet growing city with self-esteem issues in search of recognition as a destination. Veteran food critic John Lehndorff is well aware that the citys contributions to the national dining scene had a touch of absurdity: Initially, Denver was a jokeDenver Omelets and Rocky Mountain Oysters. Things changed with the arrival of people and trends. Now there are dozens of good bakeries, craft beers, ciders, and chocolatiers.

Todays clichs were not even catch phrases when a rush of neer-do-wells came to the banks of Cherry Creek during the late 1850s. The colorful image of the mining camps of Denver and Auraria, filled with men who squat and ate beans and jerky, soon gave way to a bustling outpost that could boast of an ice cream parlor as fancy anything you would visit in Chicago or St. Louis. At least that was the implication in the mining camps only newspaper, the Rocky Mountain News.

The towns first business directories strongly indicate that the first Denverites were more drinkers than diners. Saloons outnumbered places to eat by ten to one throughout Denvers first two decades. Newspaper accounts, letters to eastern homes, and diary entries show that there was a better chance at finding bad home-brewed whiskey than good home-cooked meals. Mrs. Samuel Dolman should be credited as Denvers first female restaurateur, as she sold pies to hungry miners tired of their own cooking. Mrs. Dolman used her earnings to build a boarding house. In Denver and elsewhere on the frontier, the men who left their families behind while they looked for work or gold ate at the house or hotel where they lived.

By the late 1860s, a pair of French frresFred and Louis Charpiotintroduced continental delights on Lawrence Street between 15th and 16th. When history and hot meals meet on the printed page, more often than not, the matre d is French diarist Marcel Proust. Americans might recognize the author of la Recherch du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time) as a reference in a food magazine article or book that drifts back to a recollection of a great tuna sandwich or a five-course meal. Proust probably never consulted an atlas to find Denver. Nevertheless, a contemporary, Louis Simonin, came to Denver in 1867 and wrote that a restaurant operated by one of his countrymen rivaled the botes, or cafs, that Paris had to offer.

At the same time, and a few blocks from Charpiots Hotel and International Restaurant, Chinese immigrants served whites and other Chinese along Hop Alley in Denvers Chinatown, before a race riot wiped most of it from the city in 1880. African Americans ran restaurants downtown and, increasingly, in the Five Points neighborhood by the close of the century. African American James Cole should be remembered as Denvers first celebrity chef. In other cases, the town grew so fast that stereotypes got in the way of making money or a good meal. Or so the African American women who ran their own restaurants could attest.

Early in the citys dining story, a lack of self-confidence darkened its view of its restaurants when compared to other cities. In 1883, William E. Murphy of Murphys Restaurant stated, Colorado has no typical, original food to set before the connoisseur. Murphy observed that Colorado is composed of people from the corners of the earth. A contemporary womens guide entitled

Next page