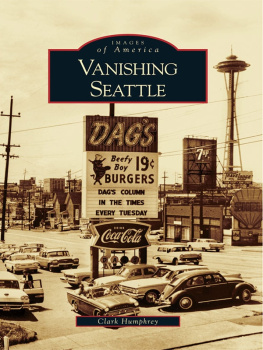

IMAGES

of America

SEATTLES

HISTORIC RESTAURANTS

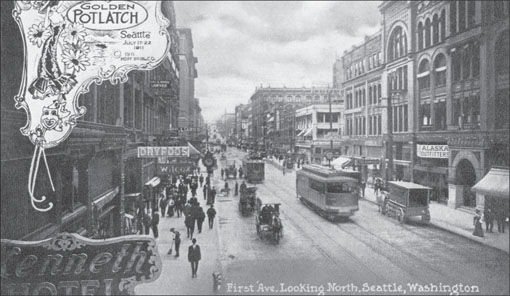

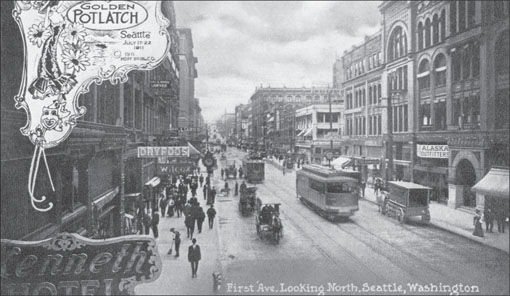

GOLDEN POTLATCH POSTCARD. Seattle held its first Golden Potlatch July 1722, 1911. The word potlatch is from the Chinook jargon, the trade language of the North Pacific Coast Indians. Potlach means a gift, or to give. In a larger sense, the Native Americans applied it to a great festival at which gifts were made. More than 300,000 people have visited Seattle for this citywide celebration of parades, concerts, and activities. (Authors collection.)

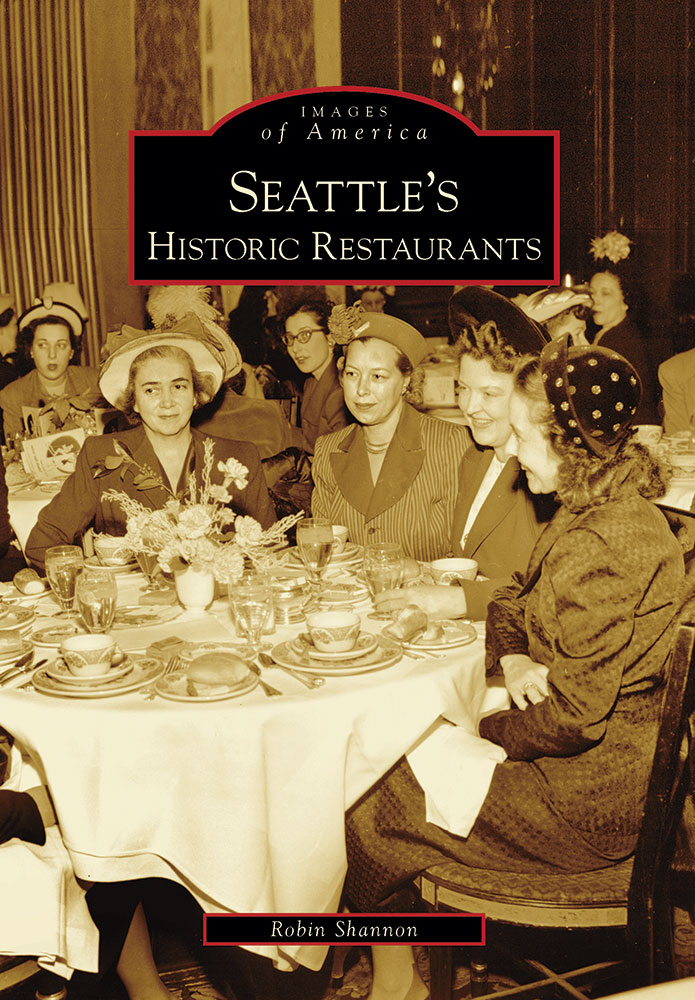

ON THE COVER: Women eat at the Georgian Room in the Olympic Hotel in Seattle in 1948. This world-class hotel, which has enchanted guests since 1924, sits on the original site of Territorial University, now the University of Washington. This five-star hotel has played host to presidents, entertainers, and royalty, delivering luxury in a timeless style. (Courtesy of Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History and Industry, No. 1986.5.9615.)

IMAGES

of America

SEATTLES

HISTORIC RESTAURANTS

Robin Shannon

Copyright 2008 by Robin Shannon

ISBN 978-0-7385-5915-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439642528

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008926297

For all general information contact Arcadia Publishing at:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Jeremy, my son, for without him this life would not be worth living. I love you, more, more, more.

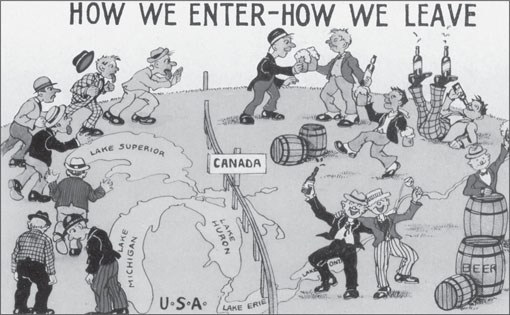

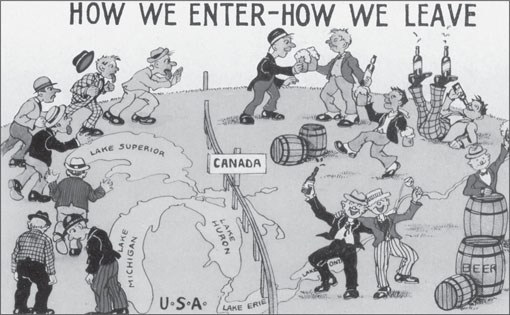

PROHIBITION POSTCARD. During Prohibition in Seattle, from 1916 to 1933, many people took a road trip north to Canada to load up on liquor. In 1933, Gov. Clarence Martin advised the establishment of a state monopoly on the sale of hard liquors and the licensing of beer and wine sales. The Washington State Legislature approved this act, and the Liquor Control Board was created. (Authors collection.)

CONTENTS

Projects such as these have contributions from a plethora of places and people. A great gratitude and recognition goes to several people and places, including the Museum of History and Industry, particularly Carolyn Marr; the Seattle Municipal Archives, particularly Jeff Ware; the Shoreline Historical Society, particularly Vicki Stiles; HistoryLink; Laurie ValBush, my friend and personal editor; the Pacific Northwest Postcard Club; Canlis, particularly Rachel Lund; the Southwest Seattle Historical Society, particularly Alan Peterson; Everett Public Library, particularly Margaret Riddle; and Julie Albright, my friend and editor from Arcadia.

I am so glad to have taken on this project because I have worked in so many restaurants in my lifetime, such as Sambos, Lil Jons, Black Angus, Barnabys, Kirkland Roaster and Ale House, Snoqualmie Falls Lodge, and the Salish Lodge. Currently, my job allows me to travel and eat in marvelous restaurants all over the United Statesmuch more enjoyable than having to slave in them. Over the years, I have collected quite a few menus. I would like to hear from the readers if they would like to contribute some memorabilia to the subject, or would like to recommend a restaurant for a possible future publication. Enjoy!

Seattle voters approved a statewide prohibition law by 61 percent in 1914. In Washington State, from 1916 to 1933, Prohibition outlawed the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages.

On January 1, 1916, Washington State joined 18 other dry states in prohibiting the sale of intoxicating liquor. The closed saloon signs said everything: Died December 31, 1915, Gone but Not Soon to Be Forgotten, Stock Closed OutNothing Left, A Happy and Dry New Year, and Closed to Open Soon as a Soft Drink Emporium.

This new law closed breweries and saloons, but it permitted private citizens to acquire permits from county auditors to import 12 quarts of beer or two quarts of hard liquor every 20 days.

A bone dry Prohibition amendment of the U.S. Constitution was passed in 1919, which then prohibited all liquor sales, manufacturing, and transportation, excluding druggists, in the United States.

The biggest bootlegger during Seattles dry years of the 1920s was Roy Olmstead. The 18th amendment that prohibited intoxicating liquor backfired; it spawned more corruption and lawlessness instead of diminishing them.

On December 5, 1933, Prohibition was repealed with the 21st amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages were no longer illegal, and the Seattle City Council enacted an emergency ordinance allowing the sale of wine and beer.

Seattle was calm on the first night of legal liquor. R. B. Berman, a reporter for the Seattle Post- Intelligencer, wrote on December 6, 1933: You walked into a bar on lower 3rd Ave. There were nine people in the place. A venerable bartender stood with folded arms, looking at the wallpaper. Brandy and soda? Yessir. No, the crowds nothing extra tonight. In fact, its very slow tonight. Must be the rain.

Blue laws in Washington State stated that taverns could only sell beer and wine, and hard liquor could not be sold. Additionally, liquor sales were forbidden on Sundays. Beer and wine could also be bought at the local grocery store. Washington State retains a monopoly on sales of hard liquor to this date. However, hard liquor can now be bought on Sundays, and taverns can now sell hard drinks if licensed.

Following the Depression, nearly everyone ate at home. In 1949, liquor by the drink became legal, which took cocktails out of private clubs and started the modern-day era of restaurants in Washington State. Elegant restaurants started serving liquor coupled with expensive dinners, creating a higher profit margin.

Many restaurants featured broiled meats. Andys Diner had a charcoal broiler that was the heart of the dining room. Canlis has been serving steaks from its charcoal broiler for 58 years. Canlis was also the first Northwest restaurant to feature an open charcoal grill where guests could watch chefs grilling prime, Midwest, dry-aged steaks; king salmon; and fresh Pacific mahimahi over Kiawe charcoal brought in from Hawaii. El Gaucho was and still is a nostalgic dining experience where steaks and seafood are broiled on a bed of coals. Panchos served From the Live Charcoal Broiler. Garskis Scarlett Tree served a sumptuous broiled lobster tail costing $2.75 from its broiler. Others that jumped on the bandwagon were Les Brainards new Grove restaurant, Clarks Crabapple, Clarks Totem Caf, and Clarks Windjammer.

The 1950s were a busy time that saw a boom of local fast food places. In the 1960s, chain restaurants popped up. Then in the 1970s, there were tons of new restaurants to choose from. Many restaurants have come and gone, and a few have stood the test of time. Fredericks Tea Room might be gone, but the Empress Hotel in Vancouver still serves an afternoon tea service. No roads lead to the Dog House, but the Space Needle still revolves in the sky. The Jolly Roger has been torn down, but the elegance of Canlis still leaves one breathless. The Snoqualmie Falls Lodge no longer has that country feel but has been transformed into the sophisticated Salish Lodge. Ivars is still Ivars. One can still order a fine cocktail at these places, but it will cost a bit more.

Next page