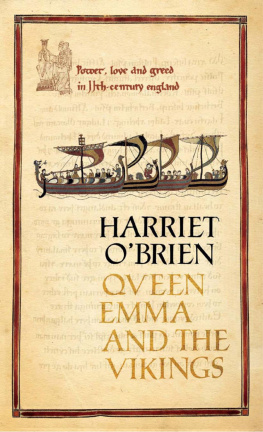

Harriet OBrien - Queen Emma and the Vikings

Here you can read online Harriet OBrien - Queen Emma and the Vikings full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Bloomsbury, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Queen Emma and the Vikings

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Queen Emma and the Vikings: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Queen Emma and the Vikings" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Queen Emma and the Vikings — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Queen Emma and the Vikings" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

QUEEN EMMA AND THE VIKINGS

A History of Power, Love and Greedin Eleventh-Century England

HARRIET OBRIEN

BLOOMSBURY

CONTENTS

She looks a little peevish, although this would not have been the intention of the artist. Doubtless he was trying to emphasise the solemnity of the occasion and the commanding nature of his patron. He shows her centre-stage, dominating the scene that she shares with three other figures who lurk subserviently to her left. The artists patron is depicted wearing a large crown that has been decorated with laurel leaves more than a hint of classical grandeur. She is seated on a bench-like throne, but an ambitious attempt at perspective gives the impression that the royal seat is a background building with a sloping roof and as a result the lady sits in midair, as if levitating a foot or so off the ground. In her hands she holds up an open book that she has turned outwards so as to invite the onlooker to wonder at its contents. Kneeling at her feet is a monk, a tiny tonsure at the crown of his head. Above him, peering around the pillar of an arch that frames the scene, are two young men with fuzzy little beards. They are also crowned. All three men look up deferentially at the seated lady. But she seems impervious to their presence: her eyes are firmly on the book.

The lady in this eleventh-century picture is a remarkable woman called Emma. The drawing depicts her receiving for the first time a book that she has commissioned. The monk is the scribe who wrote it. The young men are two of her sons. Emma lived at the tail end of a period that dismissively became known as the Dark Ages, considered as it was a benighted time of warfare, with a corresponding lack of learning and cultural activity. The paucity of surviving documentary records contributed to this image. In England, conventional history has ignored the era. Yet the so-called Dark Ages was a vast period roughly spanning the departure of the Romans in about 410 to the arrival of the Norman conquerors in 1066. Between these two momentous events were others of equal, if not greater, significance: the migration of the Saxons to England; their conversion to Christianity; the invasions of the Vikings. It was the era of the Anglo-Saxon kings under whom England gradually became a united entity.

Recently, Dark Ages has become an unfashionable term and much of the period has been relabelled Early Medieval. The rehabilitation has much justification. That bulging lump of 650-odd years swept untidily under the carpet is the root of Englishness, the Anglo-Saxon stock. And Queen Emma, at the end of the era, was the formidable catalyst for the countrys immutable change into a Norman state.

By birth Emma herself was Norman. But she effectively became the wife, mother and aunt of England. She married, and outlived, two English kings, saw two of her sons crowned and enthroned and was the great-aunt of William the Conqueror. And in 1066, fourteen years after Emma died, this blood connection gave the Norman invader a greater right to the throne of England than the incumbent Harold.

Essentially Emma was at the centre of a triangle of Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans variously jostling for control of the kingdom. (They were respectively victims, very successful chancers, and upstarts.) From political pawn Emma became an unscrupulous manipulator for power, and along the way was diversely regarded by her contemporaries as a generous Christian patron, the admired co-regent of a prosperous nation, and a callous and treacherous mother. She was, above all, a survivor, her life marked by dramatic reversals of fortune, all of which she overcame.

It was after one such fall and rise that Emma appointed a monk to write her book. The book is entirely unusual for the time. It is a political tract a work of spin written essentially to support her sons rights to the crown of England. In itself, it is palpable evidence of Emmas power and cunning. And for all its artful bias, it also gives an enormously valuable account of the world and dramatic times in which she lived. Indeed it is one of the very few records that remain from this period.

The initial manuscript no longer exists. It would have been something of a rough draft from which other, neater versions were made. We do not know how many were produced, but just one survives. This may well have been the presentation manuscript that became Emmas own copy for it carries the picture of the queen with her book, crown, throne, monk and sons as the frontispiece.

Sometime after Emmas death this book became the property of St Augustines monastery at Canterbury. Records show that it remained there until at least the fifteenth century. It is not known where it was kept during the Reformation or how it survived this period when so many church-held manuscripts were destroyed. Perhaps it was dextrously hidden, or was simply overlooked by the henchmen of Henry VIII. Its provenance remains unknown until the early-nineteenth century when it was bought or given to the tenth Duke of Hamilton. In 1882 the Hamilton library was sold to the Royal Library in Berlin, Emmas book among the stock. But five years later all these works were acquired by the British Museum. Today the book is housed in the British Library.

It is a phenomenal sensation to hold the book that she probably held more than 950 years ago; to turn the pages that she turned; to feel the faint oiliness of the vellum on which the text is written human skin against animal skin. It is a relatively small and slim volume, about seven inches long and five inches wide, its sixty-seven leaves written on each side in Latin in a brownish ink (a further page is missing). There were clearly two different scribes at work, for there are two distinct characters of handwriting and there is a change in the number of lines per page.

The embellishments, along with the picture of Emma, could have been the work of other craftsmen, some more talented than others. S, the very first letter in the book, is a decorated capital six lines deep. It is skilfully drawn as a twist of two serpent-like creatures: the top one sports tiny ears and is being devoured by the lower one, which has little legs. By contrast, F, the drop capital at the start of the next section of the book, is far less refined and looks like a hurried, somewhat botched job. However, R at the opening of the main body of the text is a wonderful concoction of tracery, swirling foliage and dog-like beasts.

But more intriguing than the ornamentations are the marks in the margins, which show the books living history. The text appears to have been closely studied during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries when annotators whose writing is identifiable to these periods added their comments also in Latin. As well as notes and corrections they have included small pictures, images that are so cartoon-like they look as if they were added with a sense of fun: there are elegantly drawn hands with long index fingers pointing to passages that were considered particularly significant; there is a crowned head beside the section where Emmas second husband becomes king of England; and there is black humour, for next to a description of how one of Emmas sons was blinded, a pair of eyes peers out from the margin.

The covers of the book are of an even later date: they are leather, probably an early-nineteenth-century contribution. Originally the pages would have been bound on to wooden boards that may have been covered with sheepskin and then decorated with metalwork. It does seem astonishing, though, that for all the changes in production and materials the very form of a book has not altered at all since at least the eighth century. A book is and was a series of written (and often illustrated) rectangular pages that were and are folded, then stitched together (or now more often glued) and finally enclosed in protective covers.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Queen Emma and the Vikings»

Look at similar books to Queen Emma and the Vikings. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Queen Emma and the Vikings and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.