Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Josh S. Cutler

All rights reserved

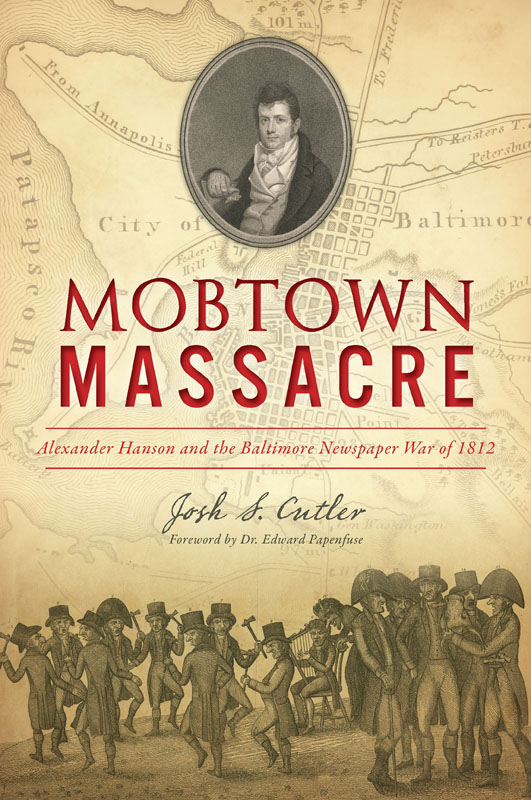

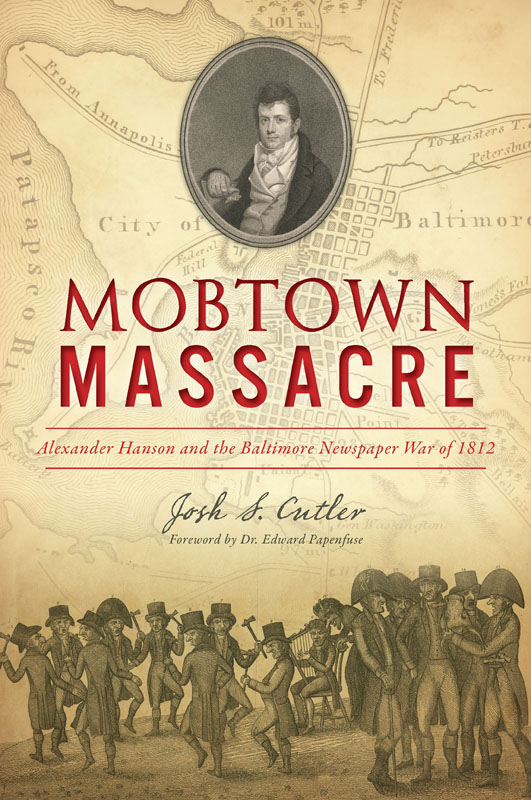

Front cover: The Conspiracy against Baltimore or The War Dance at Montgomery Court House, 1812 engraving by unknown artist. Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society.

First published 2019

e-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.620.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018960976

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.227.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

A compelling story thats as timely today as it was two centuries ago.

Congressman William R. Keating

A remarkably vivid, engaging and very readable account of a brief but major event in Baltimore history, and the significant personalities involved, which reflected the sharp political divisiveness of the time at the start of the War of 1812, and had important implications for freedom of the press and the war itself, and for Baltimores lasting moniker of Mobtown.

Charles Markell, board member, Baltimore City Historical Society

Mobtown Massacre is a timely and scholarly examination of one mans struggle for freedom of the press. Denied by word and brutal mob attacks, leaving deaths and injuries that defined a city and shaped a nations very notion of freedom of the press.

Fred Dorsey, Howard County historian

For Dad

CONTENTS

Foreword

HANSON:

PROTEST AND RIOT OF 1812

As anyone who has studied civic unrest and mob action knows, mobs can, and often do, take on a mind of their own, leading to unintended consequences of property destruction and death. Paul Gilje, in his seminal article on the Baltimore mob of the summer of 1812 (Journal of Social History 13, no. 4 (Summer 1980): 54764), probes one of the earliest mob actions in the life of the republic and gave Baltimore the nickname of Mobtown, a moniker that the city has not been able to live down to the present day when attempting to deal with the aftermath of the death of Freddie Gray. In the latter instance, the city authorities acted quickly to stem the excesses of what began as a reasonable political protest on the part of high school students and mushroomed into a looting spree successfully contained without bloodshed. The circumstances in the summer of 1812 were different. Civic leadership was bewildered and uncertain how to act. The mob ruled, resulting in the death of a Revolutionary War hero and the severe beating of the newspaper editor who, undoubtedly, with his printed words and his provocative actions, precipitated the violence.

The Baltimore riots and mob action of the summer of 1812 had their origins in a written war between two Baltimore newspaper editorsAlexander Contee Hanson and Baptis Irvinein the context of a bitter party rivalry that pitted Jeffersonian Democrat-Republicans against Washington-worshiping Federalists. In its most basic form, the Democrats favored punitive action against Great Britain for its depredations of American shipping and the impressment of American sailors on the high seas, while the Washington Federalists opposed war and favored the first presidents caution against foreign entanglements. Beginning as early as 1808 in the pages of the Baltimore Whig (Irvines newspaper) and the Baltimore Republican (Alexander Contee Hansons newspaper) and pursued in the courts, Hanson and Irvine battled it out in print and before juries. The courts (including a court-martial of Hanson for refusing to take up arms against the British) found in favor of Hanson. Irvine smarted and perhaps played an instrumental role in whipping up the mob to destroy the printing office of Hansons in Baltimore and then pursue Hanson and his associates to their bloody beating when Hanson returned to reestablish the paper and his voice in the city.

Paul Giljes article provides a succinct account of the mobs emergence and actions. It is rightfully critical of the assault on the freedom of the press and provides a useful overview of the story that Josh Cutler tells so well in the following pages. Here in an engaging narrative drawn from the literally hundreds of pages of testimony, court records and editorial comment from around the infant nation, the full story of Alexander Contee Hansons defense of an unfettered press is told with readable fairness and a sense of the times that leave the reader fulfilled by the story but wanting to know more, eager for the next installment.

It is perhaps fair to say that Baltimore in the first two decades of the nineteenth century is an enigma that historians have yet to fully puzzle out and unravel. It was an urban miracle in the midst of a slaveholding plantation society that within a small geographical imprint expanded from 8 percent of the total population of Maryland to a nearly doubled 15 percent by 1820, including a rapidly growing free black population that posed a rising threat to the stability of the rest of the slaveholding state. In those years, the focus of the city was on its commercial expansion, both legal and extralegal. Baltimore was notorious for its advocacy of disrupting and capturing enemy shipping, supplying rebels in Central and South America, and in the expansion of American territory to the north and to the south. New Orleans became a trading partner of the highest order both in agricultural products (rice, sugar and cotton) and slaves. Protecting that trade from the depredations of the British and advocating expansion of territory and trade into Canada was the objective of its merchants and the war cry of the mob.

In this narrative, Josh Cutler focuses on the story of what happened in Baltimore in those summer months of 1812, raising the specter that the actions of Alexander Contee Hanson were motivated in part by a desire to advance his own political career. Whether or not that was the case, Hanson did win his election to Congress that fall, galvanizing the electorate in support of the Federalists statewide. For the next decade, the Federalists would control the general assembly and the statehouse, and Alexander Contee Hanson would become a U.S. senator from Maryland, a post he held until his death at thirty-three in 1819.

As to the leaders of the mob of the summer of 1812 and their followers, they were acquitted by juries of their peers and lived to lead another day, with perhaps the greatest irony being the career of the butcher Mumma, who probably led the assault on the jail that led to death of General Lingan and who by 1820 was no less a justice of the peace in the city. As to Baptis Irvine, he persisted in his advocacy of war and participated in the invasion of Canada as the second lieutenant of the First Baltimore Volunteers, who raised the American flag over York, Canada, and helped torch the Canadian capital, an action that the British claimed was their reason for burning public buildings in Washington, D.C., in the summer of 1814. Irvine may also have been the first imbedded reporter in a military unit, as his reports of his and his units exploits along the Canadian border were published in the

Next page