Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2021 by Josh S. Cutler

All rights reserved

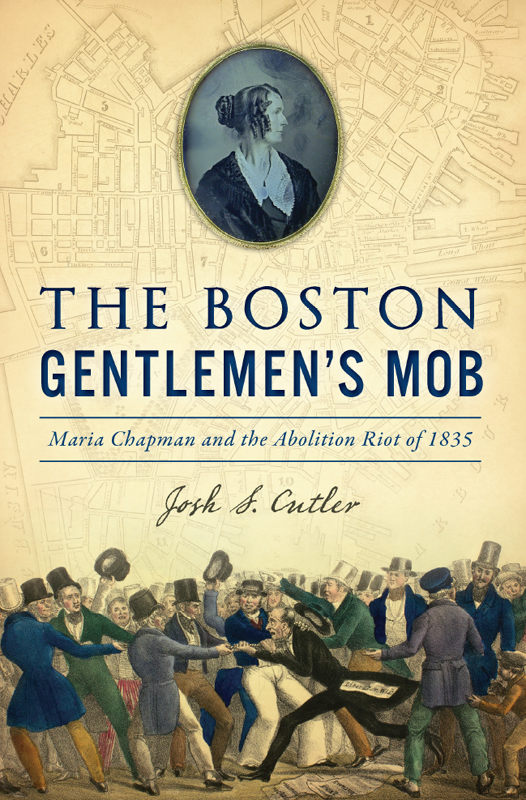

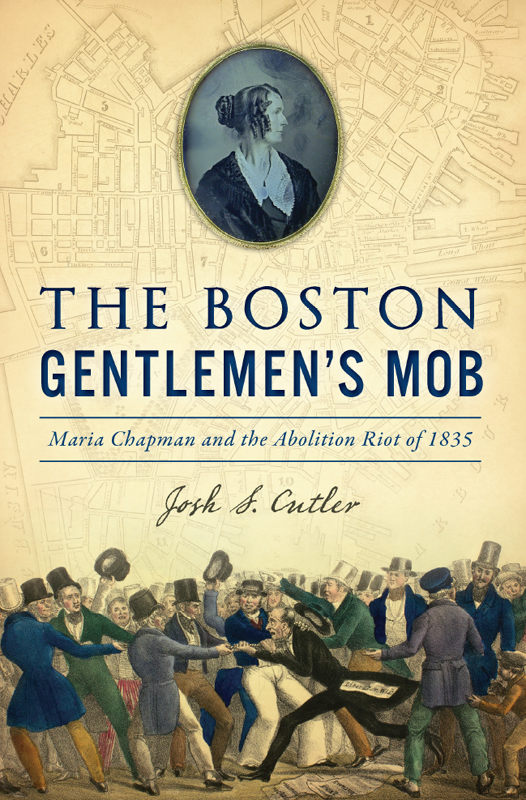

Front cover, top: Maria Weston Chapman. Boston Athenaeum; bottom: The Abolition Garrison in Danger & the Narrow Escape of the Scotch Ambassador. October 21, 1835. Library Company of Philadelphia.

E-Book year 2021

First published 2021

ISBN 978.1.4396.7397.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021945865

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.4671.5091.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Charlie, Delilah, Jack and Connor

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

History is filled with pivot points we can look back on and recognize as significant, and the events of October 21, 1835, certainly qualify. Its been a pleasure diving into this subject matter to share this compelling story, and Im grateful to everyone who helped along the way. That certainly includes my team of beta readers who shared valuable feedback and edits, especially Tom OBrien, John Galluzzo, David Mittell Jr., Ben Cutler and Suzanne Cutler.

Id also like to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their assistance: Marta Crilly and Meghan Pipp from the Boston City Archives; Rob MacLean and the staff at Weymouths Tufts Library; Christopher Cantwell for assistance tracking down some key letters; Merlyn Liberty from Abingtons Dyer Memorial Library; Kate Long and the Smith College Special Collections Department; Carolyn Ravenscroft and the Duxbury Rural and Historical Society; Leon Wilson and team from the Museum of African American History; Daniel Hinchen and the staff of the Massachusetts Historical Society; Diana Flemer, former chair of the Weymouth School Committee; and the staff at the Boston Athenaeum, Massachusetts State House Library, Boston Public Library, Historic New England and Harvard Universitys Houghton Library.

This is my second time publishing with The History Press. I am pleased to have worked with Mike Kinsella and their team of editors.

Thank you to Lori for all the love and support.

Part I

1835

Maria Chapman, circa 1850. American Magazine.

MAYOR LYMAN: Ladies, do you wish to see a scene of bloodshed, and confusion? If you do not, go home.

MARIA CHAPMAN: Mr. Lyman, your personal friends are the instigators of this mob; have you ever used your personal influence with them?

MAYOR LYMAN: I know no personal friends; I am merely an official. Indeed, ladies, you must retire. It is dangerous to remain.

MARIA CHAPMAN: If this is the last bulwark of freedom, we may as well die here, as anywhere.

Chapter 1

SUSAN PAUL

The rapid progress of the causewill, ere long, annihilate the present corrupt state of things and substitute liberty and its concomitant blessings.

BOSTON, OCTOBER 21, 1835There was no peace officer on site when Susan Paul arrived, only two grinning boys standing by the door who scampered off at her approach. It was shortly after two oclock on a Wednesday afternoon, and Paul was joined by a handful of women in front of the antislavery office. The clippity-clop sound of hooves and the creak of carriage wheels rumbled past them on Washington Street.

The women expected trouble and cautiously entered the wood-framed building, climbing two flights of stairs to the lecture hall where the annual meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society was to be held. Their meeting had already been postponed once. The original location was rejected by the buildings owner after bowing to pressure from men of property and standing who opposed the societys abolitionist aims.

As Paul made her way upstairs, the passageway to the hall soon began to fill with unwelcome guests who cleaved to the walls and clogged up the way. The men hissed and heckled the women, and a few lobbed orange peel scraps their way. Some stood on the shoulders of others and glared over the partitionthough none had yet dared breach the actual lecture hall where the meeting was to be held.

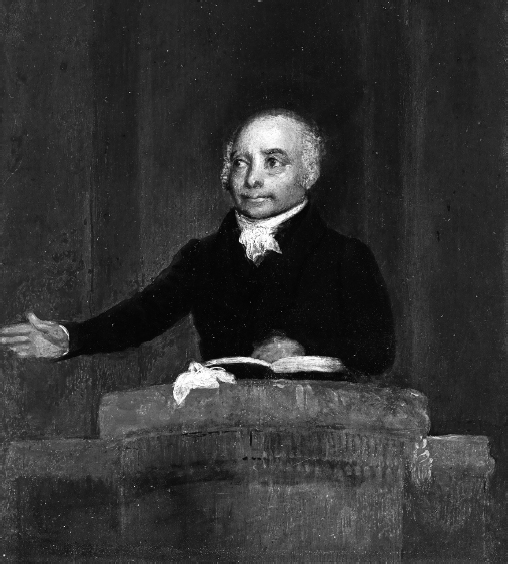

Reverend Thomas Paul. Smithsonian.

While the women greeted one another and settled in their seats, they sent a young boy downstairs to the street entrance to advise any late-arriving members that there was still room inside. Outside, it was an unseasonably warm October day, and inside tempers were also heated. Five more women pushed through and mounted the stairs, but many others turned away, unableor unwillingto confront the swarming crowd.

The lecture hall was arranged with plain wooden benches and a raised speaking platform. For Susan Paul, a seamstress and schoolteacher, the scene was reminiscent of a classroom. She took her seat along with her fellow members of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society as they awaited the arrival of their special guest. There were about twenty-five women in the room, most of them whitesave Paul and a handful of others, including Lavinia Hilton and Julia Williams.

There are no known images of Susan Paul. Her sister Anne Paul Smith (left) died shortly after giving birth to her daughter, Susan Paul Smith (right), and Paul helped raise her. UNC Chapel Hill.

As its name announced, the society was avowedly antislavery, but until recently it had only included white women among its members. Despite being well-educated and warmly loved and respected by her fellow abolitionists, it was not until outside pressure was applied that Paul was invited to become a member.

The issue had come to the fore when William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of the abolitionist newspaper the Liberator, was invited to speak shortly after the groups formation in the fall of 1833. Garrison saw the invitation as an opportunity to teach a lesson and declined. Instead, he urged the all-white womens society to engage in some self-reflection, declaring it shocking to my feelings that the members of an antislavery society would themselves be slaves of a vulgar and insane prejudice.

Garrisons message was heard with respect, and the board agreed to his request. I am happy to inform you that our decision was on the side of justice, that we resolved to receive our colored friends into our Society, and immediately gave one of them a seat on our Board, they replied, referring to Susan Paul. Thus, the society was now integrated, though equality remained elusive.

Next page