Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Michelle Arnosky Sherburne

All rights reserved

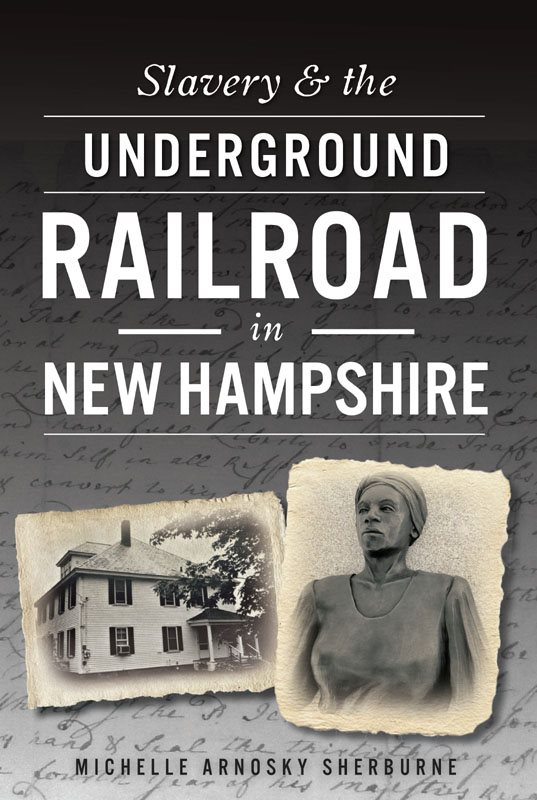

Front cover: Furber-Harris House now on Cardigan School property. Courtesy of Donna Zani-Dunkerton private collection; Entrance statue of the Portsmouth African Burying Ground. Courtesy of Michelle Arnosky Sherburne. Portsmouth African Burying Ground Memorial and Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail site; Amos Fortune unsigned manumission document, 1763. Courtesy of the Amos Fortune Collection in possession of the Jaffrey Public Library.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.637.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954742

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.834.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to my parents, Jim and Deanna Arnosky, who have always been my inspiration, my source of encouragement and my pillars of strength.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Valerie Cunningham is the founder of Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail Inc. She is responsible for the initial discovery of black heritage and slavery while researching Portsmouth, New Hampshires history. In the book Harriet Wilsons New England: Race, Writing, and Region, Cunningham wrote an essay about Portsmouths black heritage. Cunningham wrote:

Recent studies have shown that from the time of its earliest settlement, New Hampshire merchants, shipbuilders and seamen were active participants in the transatlantic slave trade and the slave-based economy that helped build this country. Yet these memories quickly faded as New England states removed legalized slavery from the region. By the mid-nineteenth century, the subject of slavery in New Hampshire had been reduced to anecdotes in town histories and popular publications of the day.

In terms of population, a majority of blacks in New Hampshire had been concentrated within a twenty-mile radius of Portsmouth since 1645. In 1760, enslaved black workers accounted for 4 percent of Portsmouths population, about 160 people out of 4,000. As Portsmouths African American population grew older, its numbers became smaller, and as the people disappeared, stories of slavery days seemed to vanish with them. Of course, it is precisely this very forgetting in town histories and records that resulted in the loss of black heritage altogether.

Slavery was not abolished in New Hampshire in a bold obvious move, such as Vermonts claim of being the first state to do so. It wasnt until 1857 that the legislature enacted an equality ruling that no person, because of descent, should be disqualified from becoming a citizen of the state. This act has been accepted as abolishing slavery, but technically it didnt come right out and do so. New Hampshire wasnt legally cleared until the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 abolishing slavery in the country; the state ratified it on July 1, 1865.

The international slave trade in the United States ended in 1807, which altered Portsmouths shipping industry of importing slaves. Regardless, most slaves were manumitted by their owners one by one, perhaps because the declining postwar economy could no longer provide enough business to offset the financial burden of maintaining unpaid laborers in the household.

As slave labor was routinely replaced by low-wage white workers, former slaves and their descendants in New Hampshire were perceived by non-blacks to be part of the social and economic servant class that would eventually include all black Americans. White America defined servants as Negroes and Negroes as servants. This attitude continued for at least a century after Harriet Wilson wrote the novel Our Nig; or, Sketches from the Life of a Free Black. African Americans were competing with the newest wave of immigrants for the most menial jobs or were reinventing themselves as entrepreneurs, working as day laborers or laundresses, cooks or caterers, mariners or landlords, footmen or truckers, maids or seamstresses.

In 1857, New Hampshire officially declared itself to be a free state. Portsmouths role in the Atlantic slave trade and slaveholding was being erased from public memory. Slaves and their owners were no longer mentioned in the publications of the day. The emphasis had shifted from ownership of slaves to their representation in more stereotypical, childlike guise. Non-blacks in New Hampshire seemed only too willing to forget the complicity of the founding fathers and their own economic dependence on the slave-based economy. References to the presence of slaves were typically modified by declaring that there never had been very many or that a black servant complemented the elegant lifestyle of the master.

At the turn of the twentieth century, while the South romanticized its preCivil War relationship with slavery, most of New England denied ever having such a past. Until recently, New Hampshire may not have remembered its own history, but as the stinging reality of the 2003 unearthing of a black cemetery under a Portsmouth street shows, that history is surfacing more forcefully all the time.

Discover Portsmouth director JerriAnne Boggis is the founder of the Harriet Wilson Project in Milford, New Hampshire. In her essay published in Harriet Wilsons New England, Boggis wrote about the black history in the town she lived in for years. Boggis wrote the following:

One never had to look too far or search too hard for signs of his white history, his heritage. It is written. It is visible. It is concrete. It is a story that is told and retold in the books my sons have read in school since they were six. It is the story of our state that is told and retold through the ubiquitous images of verdant hills, a pastoral setting and a pure Anglo-Saxon lineage.

And that was how I discovered that Harriet E. Wilson, the first black woman to publish a novel in the United States and the author of Our Nig: or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, was born and raised here in Milford, the town Ive lived in for more than 23 years.

And as I read, an unimagined and more complex picture of our towns history began to form. The myths I had accepted began to crumble. First, Milfords history was not lily-white.

As truth has been revealed by historic discoveries in recent years, New Hampshire was not either. Who was responsible for this whitening of history?

The second myth that would fade away was the belief that our town, like the rest of the North, had been a safe haven for blacks and that its inhabitants were kinder than their Southern counterparts.

But here was a second story of our town, a story that could have come from the slaveholding South. I was horrified by the extent of brutality Frado experienced and was even more dismayed that sympathetic observers had not intervened on her behalf. Wilson showed just how easy it is to be invisible in plain sight.

Next page