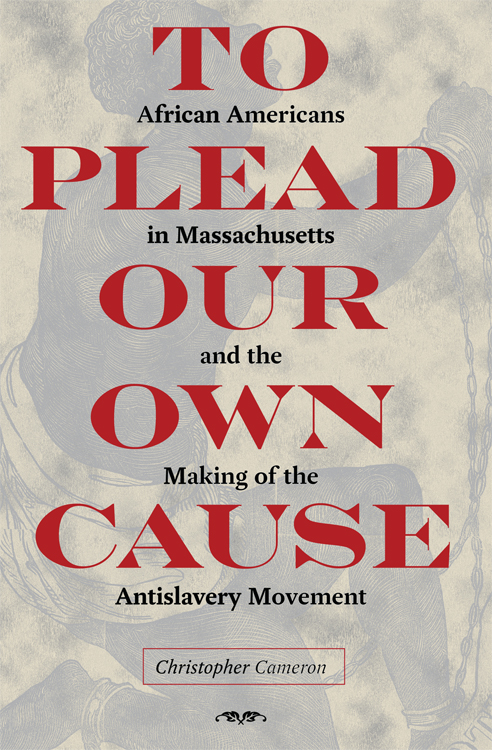

TO PLEAD OUR OWN CAUSE

AMERICAN ABOLITIONISM AND ANTISLAVERY

JOHN DAVID SMITH, SERIES EDITOR

The Imperfect Revolution: Anthony Burns and the Landscape

of Race in Antebellum America

GORDON S. BARKER

A Self-Evident Lie: Southern Slavery and the Threat to American Freedom

JEREMY J. TEWELL

Denmark Veseys Revolt: The Slave Plot That Lit a Fuse to Fort Sumter

JOHN LOFTON NEW INTRODUCTION BY PETER C. HOFFER

To Plead Our Own Cause: African Americans in Massachusetts

and the Making of the Antislavery Movement

CHRISTOPHER CAMERON

To Plead Our Own Cause

African Americans in Massachusetts and

the Making of the Antislavery Movement

CHRISTOPHER CAMERON

THE KENT STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Kent, Ohio

2014 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2013042583

ISBN 978-1-60635-194-9

Manufactured in the United States of America

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Cameron, Christopher, 1983

To plead our own cause : African Americans in Massachusetts and the making

of the antislavery movement / Christopher Cameron.

pages cm. (American abolitionism and antislavery)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60635-194-9 (hardcover)

1. African American abolitionistsMassachusettsHistory. I. Title.

E445.M4C36 2014

326'.80922dc23

2013042583

18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

This book began nearly a decade ago as a ten-page paper on religion in the British and American abolitionist movements. My undergraduate adviser at Keene State College, Gregory Knouff, encouraged me to develop the paper into a larger project, and this study is the final result. I am indebted to Greg for his support and friendship over the years. Matthew Crockers course on the Early Republic was instrumental in my deciding to pursue history, while Joseph Witkowski and Vincent Ferlini both chose me to serve as their undergraduate teaching assistants, which were important experiences when deciding to enter academia. Antonio Henley and Amanda Powell at the University of New Hampshires Ronald E. McNair Program successfully convinced me to attend graduate school, and I will be forever grateful that they did so. Many thanks also to Funso Afolayan, my McNair mentor, for guiding this project along at its earliest stages.

I cannot say enough about the invaluable support, advice, and encouragement I received from my dissertation adviser, Heather Andrea Williams, as well as the insightful criticism and assistance of my dissertation committee members at the University of North CarolinaKathleen DuVal, Lloyd Kramer, Laurie Maffly-Kipp, and Jerma Jackson. Other members of the faculty there who commented on portions of the work include John Wood Sweet, Jacquelyn Hall, and Rebecka Rutledge Fisher in the English department. My graduate colleagues in the history department at UNC were similarly invaluable to the completion of this study. Randy Browne carefully read each chapter of the manuscript and always offered excellent criticism. This project is what it is largely due to his assistance. Ben Reed, Jennifer Donnally, Eliot Spencer, Catherine Conner, Brandon Winford, and David Palmer read parts of the project and helped make both my arguments and writing stronger. My colleagues at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte likewise read portions of the manuscript in our departments Brown Bag Seminars. I very much appreciate their excellent advice and support over the years. Special thanks to my colleague and series editor John David Smith, who was instrumental in this books publication, as well as Manisha Sinha and the other anonymous reader at The Kent State University Press for their insightful comments and criticism.

I have received generous financial and research support from a number of different sources. These include the Department of Educations Ronald E. McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program; the Royster Society of Fellows at the University of North Carolina; the UNC history departments Mowry Dissertation Fellowship; the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History; and the Peabody Essex Museum. At UNC Charlotte, a Faculty Research Grant and a Small Grant were instrumental in helping me complete the manuscript. The staffs at the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston Public Library, Congregational Library, Massachusetts Archives, Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum, Rhode Island Historical Society, New-York Historical Society, and Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture provided invaluable assistance.

Finally, I would like to thank my family. Alain and Lynn Cameron, as well as Rejean and France Cameron, opened up their homes during multiple research trips. Before she passed away, my grandmother Gisele and my grandfather, Real Cameron, did likewise. Many thanks also to my siblings, and to my wonderful wife, Shanice, for her love and encouragement. Most of all, I would like to thank my mother, Sylvie Cameron, for keeping me grounded and always being there for me. This book is dedicated to her memory.

In one of the most significant antislavery tracts published in antebellum America, Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829), David Walker, a black activist residing in Boston, articulated many of the most prominent themes in American abolitionism, including a rejection of the colonization plan, a call for black unity, and the idea that God would be on the side of the oppressed. Though our cruel oppressors and murderers, may (if possible) treat us more cruel, as Pharoah did the children of Israel, Walker wrote, yet the God of the Etheopeans, has been pleased to hear our moans in consequence of oppression; and the day of our redemption from abject wretchedness draweth near, when we shall be enabled, in the most extended sense of the word, to stretch forth our hands to the LORD our GOD.

While most studies of the antislavery movement begin their examination in the 1820s, Walkers blend of religious and political rhetoric in the cause of abolitionism was a tactic African Americans had employed in the fight against slavery since the eighteenth century. One such predecessor was a As Walker would later do, Sarter argued that a righteous God would be on the side of slaves and would judge America for the sin of slavery.

It is a common understanding in the scholarship on abolitionism that the radical abolitionist movement did not begin until the 1830s. David Walkers Appeal and William Lloyd Garrisons publication of the Liberator beginning in 1831 are seen as the opening salvos in this new, radical phase of the antislavery movement. Sarters rhetoric and calls for immediate emancipation, however, along with that of many of his contemporaries in Massachusetts, suggest that eighteenth-century abolitionism was just as radical as its nineteenth-century counterpart and that the origins of abolitionism in America can be found among blacks in Massachusetts. This is the first study to trace these origins to African Americans in the Bay State and explore the significance of Calvinism to their antislavery ideology.

The demographics of Massachusetts, rights given to slaves within the colony, and the injunction of ministers to Christianize slaves aided in the formation of a black community that began to challenge slavery in the public sphere during the revolutionary period. In Massachusetts, slavery itself was shaped heavily by Old Testament law, which said that slaves should have specified rights. Thus, early Puritans allowed slaves to petition the government and bring cases in court. Furthermore, religious leaders in the colony urged their parishioners to Christianize slaves, a practice that extant church records indicate was followed by a number of owners. The fact that slaves never made up more than 5 percent of the colonys population and the lack of overt rebellions (such as the 1739 Stono Rebellion in South Carolina) made the colony more conducive to allowing slaves liberties that they were summarily denied elsewhere.