Acknowledgments

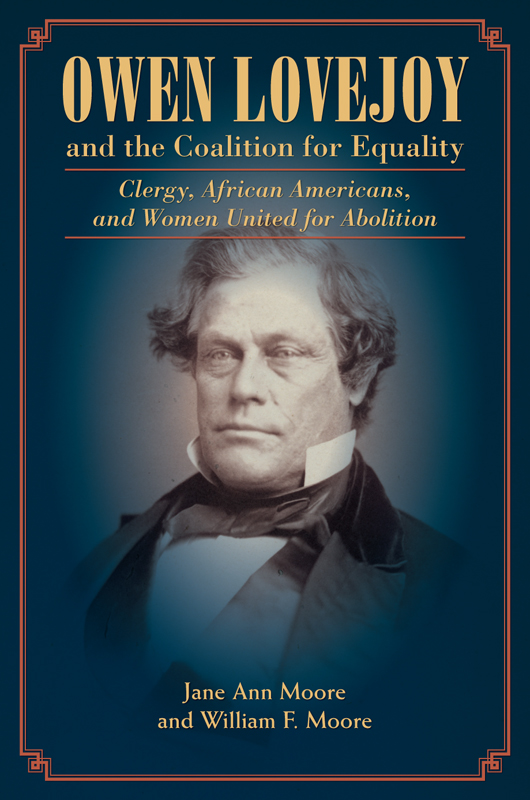

We want to express our gratitude to those who brought us to the story of nineteenth-century interracial collaboration in Illinois. These are the people who pointed us toward an understanding of the depth of the struggle experienced by African Americans in antebellum and Civil War times and by Owen Lovejoy and the political abolitionists included in the coalition for equality.

They include hosts and friends who, out of commitment to human equality, led us during the summers we spent in West Africa. They include the faculty and students who mentored us while we taught African studies at Howard University, as well as our black and white, male and female clergy colleagues in the Washington, D.C., area, including Rev. Ted Ledbetter and Gretchen Eick, who worked with us in the effort to end American investment in apartheid South Africa.

Some were found among the progressive citizens of Montgomery County, Maryland, led by Idamae Garrett, who invited Jane Ann to run as a candidate and serve on the County Council in the 1974 Year of the Woman. Others stood out among the black citizens of Benton Harbor, Michigan, who dared to plan a gala Martin Luther King Jr. celebration with white citizens from St. Joseph. Still others gather together today in coalitions of diversity in DeKalb, Illinois, activists in the interfaith network, the Beloved Community, the Micah Group of interracial clergy, and the Lovejoy Society, and in Oak Park, Illinois, inside Pilgrim United Church of Christ, which is working to become a multicultural congregation.

We are grateful to Edward Magdol, whose 1967 biography of Owen Lovejoy in the DeKalb Public Library captured our imagination in 1994 and never let us go. We are indebted to the black churchmen and -women of the Chicago Friends of the Amistad Research Center who have been preserving precious documents of black history in the Amistad Archives in New Orleans; to its founder, Clifton Johnson; to Rev. Dr. Sterling Cary, former Illinois Conference Minister, UCC; to Rev. Dr. Kenneth Smith, former president of Chicago Theological Seminary; and to the Chicago Friends current leader, Willie Lee Hart.

The Society for Historians of the Early American Republic (SHEAR), an unusual academic group that encourages young historians in research and publication, graciously included us and gave direction to our research. We especially thank Frederick J. Blue, whose own research recognized the unusual contributions of Owen Lovejoy and who opened doors for us. We remember Merton Dillon in southern Michigan: his enthusiasm for antislavery research in Illinois, his discovery of the Lovejoy family letters, and his success in finding a home for them in the archives of Texas Technological University at Lubbock. We value the professional leadership James Brewer Stewart has given to SHEAR, as well as Stewarts appreciation of the roles Christianity played during the antebellum years.

In Illinois Tom Schwartz directed us to material about Lovejoy when the state library was still squeezed under the Old Capitol and later when it relocated to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, which he headed. Always ready to help was director Katherine Harris, now president of the Abraham Lincoln Association. William Furry, director of the Illinois State Historical Society, alerted us to new material, and John Hoffman hunted down sources for us at what is now the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections in the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library.

Those who coached us through reading and critiquing our successive manuscripts deserve our deep appreciation. They include especially Frederick J. Blue and also Sarah Cooper, Sarah Criner, Maylan Dunn-Kenney, Bob Hey, Clinton Jesser, Lolly Voss, Marlene Meeter, John and Carol Stoneburner, and Tony Stoneburner. We give additional thanks for technical assistance from Bill Feldman and Kyle Kent.

Research offers zestful moments. We remember the young technician at Andover-Newton Seminary who discovered online the existence of an article by Lovejoys grandson at Cornell University. We remember the devotion of Phil and Janet Dow in Albion, Maine, who keep the spirit of the Lovejoy family alive in that town. We remember the archivist at the McLean County Historical Society who handed us the unidentified handwritten manuscript of Lovejoys 1862 Cooper Union speech. We remember Julie P. Winch, who sent us pivotal issues of the Christian Recorder that opened up a new path in our research; and we will not forget Lorna Vogt and Phyllis Kelley, who gave us important resources, such as our very own copy of the 1855 Journal of the Illinois General Assembly. Julia Edgerley, a historian from Granville, Illinois, bequeathed her well-read 1951 microfilm copy of Dillons dissertation, The Antislavery Movement in Illinois, and Pam Lang acquainted us with Lovejoy papers in the Bureau County Historical Society Archives in Princeton, Illinois.

We are grateful to the peer reviewers of the University of Illinois Press, and to the perceptive and concise UIP acquisitions editor Dawn Durante and assistant director Jennifer Comeau, who helped shape and sculpt the manuscript into a book.

Finally, in the midst of everything is our family, Deborah, Bill, Kyle, Kaitlin, and Watson, who give us constant inspiration and gifts of cutting-edge books on American history, and who respond to almost every question with the rousing answer, It must be Owen Lovejoy!

We also acknowledge Owen Lovejoy himself. Of all the politically active pastors and laymen involved in the antislavery movement in Illinois, the Reverend Owen Lovejoy was the one elected to the United States Congressand when he got there, he made an indispensable difference.