Standard-Bearers of Equality

AMERICAS FIRST ABOLITION MOVEMENT

PAUL J. POLGAR

Published by the

OMOHUNDRO INSTITUTE OF EARLY AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE,

Williamsburg, Virginia,

and the

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS,

Chapel Hill

The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture (OI) is sponsored by William & Mary. On November 15, 1996, the OI adopted the present name in honor of a bequest from Malvern H. Omohundro, Jr., and Elizabeth Omohundro.

2019 The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cover illustration: Detail of Seal of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. Pennsylvania Abolition Society Papers. Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Polgar, Paul J., author. | Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, publisher.

Title: Standard-bearers of equality : Americas first abolition movement / Paul J. Polgar.

Description: Williamsburg, Virginia : Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture ; Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019027186 | ISBN 9781469653938 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469653945 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of SlaveryHistory. | New-York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and Protecting Such of Them as Have Been, or May Be LiberatedHistory. | Antislavery movementsMiddle Atlantic StatesHistory18th century. | Antislavery movementsMiddle Atlantic StatesHistory19th century. | Free African AmericansPolitical activity. | African AmericansCivil rightsHistory. | United StatesRace relationsHistory.

Classification: LCC E446 .P65 2019 | DDC 305.800973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019027186

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

To

Valerie, Arlene, Josephine,

and my parents

Your love is my foundation

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Reimagining American Abolitionism

1. THE MAKING OF A MOVEMENT

Progress, Problems, and the Ambiguous Origins of the Abolitionist Project

2. THE JUST RIGHT OF FREEDOM

Enforcing and Expanding Gradual Emancipation

3. REPUBLICANS OF COLOR

Societal Environmentalism and the Quest for Black Citizenship

4. A WELL GROUNDED HOPE

Sweeping Away the Cobwebs of Prejudice

5. UNCONQUERABLE PREJUDICE AND ALIEN ENEMIES

The Roots and Rise of the American Colonization Society

6. A PRUDENT ALTERNATIVE OR A DANGEROUS DIVERSION?

First Movement Abolitionists Respond to Colonization

EPILOGUE

A Movement Forgotten

Illustrations

FIGURES

TABLES

Standard-Bearers of Equality

INTRODUCTION

Reimagining American Abolitionism

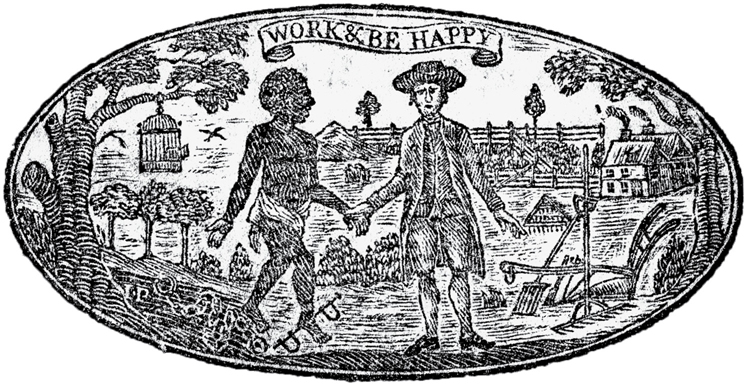

He should be standing, not kneeling. This was the conclusion the Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS) had reached in the fall of 1789 as the group reviewed an illustration that might serve as the centerpiece of the certificates of membership for the newly reconstituted organization. They were most likely referring to Josiah Wedgewoods famed depiction of an enslaved man on bended knee pleading, Am I Not a Man and a Brother, printed in London two years earlier and embraced by abolitionists throughout the Atlantic world (

FIGURE 1. Seal of the Society for Promoting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. From James Field Stanfield, Observations on a Guinea Voyage; in a Series of Letters Addressed to the Rev. Thomas Clarkson (London, 1788). Courtesy, the Library Company of Philadelphia

The emblem that the PAS ended up adopting reflects Pembertons unbridled optimism. Whereas Wedgewoods original design cast a man weighed down by chains and with hands clasped in pleading, almost desperately, for deliverance from bondage, the PASs seal projected a very different conception of abolitionism and black freedom. In the PASs image, the black man stands tall and appears in mid-stride, chest open, arm extended, and one palm facing out, as if greeting freedom with an assured sense of self-possession. Though the traces of bondage remain, unlike in Wedgewoods illustration the manacle in the PAS seal lies broken at the formerly enslaved mans foot, implying that slavery would not continue indefinitely to define either people of African descent or the new nation in which they lived ().

The formerly enslaved man in this etching does not stand alone. His gaze is fixed upon a white abolitionist who has taken the black mans left hand and is looking forward, seemingly announcing to the world the arrival of a new epoch characterized, not by racial slavery, but black liberty and empowerment. The white activists presence projects the conviction of abolition societies such as the PAS that they would play a key role in assisting enslaved peoples transition to free persons, even as it indicates that the cause of emancipation would be a joint effort made up of both white and black actors. Yet the seal also implies a vision of the young Republic in which people of color are included, their humanity recognized, their belonging confirmed, their rights as members of the new nation self-evident.

FIGURE 2. Seal of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. Papers of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. The seals heading, Work and Be Happy, suggests that the PAS sought to repurpose ideas of black labor that, when associated with slavery, invoked subjecthood and degradation as instead an outlet for self-fulfillment and virtue. At the same time, the heading gestures to how the PAS, and other abolition societies, intended to carefully structure African American freedom. Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The sentiments embodied in the PASs seal were not mere fantasy, and neither did the society have to look to an illustration alone to confirm its brand of antislavery reform. A decade and a half after the PAS created its trademark, Peter Williams, Jr., a free black minster and abolitionist, communicated to a group of abolition societies that included the PAS a similar understanding of emancipation and black liberty. Whereas African Americans had once been held as beasts of burthen and reduced to the deplorable situation of human bondage, the tide of oppression was now falling away. Instead, Williams was struck that abolition societies were helping to place thousands at liberty, and are daily casting off the shackles of numbers more. By rising above the mean prejudices imbibed against people of color, abolition societies had been instrumental in striving to assure that equal justice is distributed to the black and the white. These developments indicated that just over the horizon lay a promised land in which America would eliminate all distinctions between the inalienable rights of black men, and white, Williams boldly predicted.