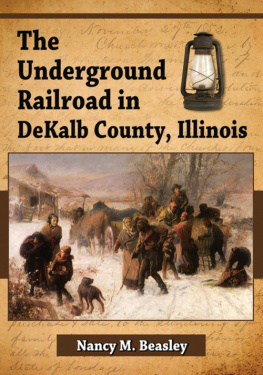

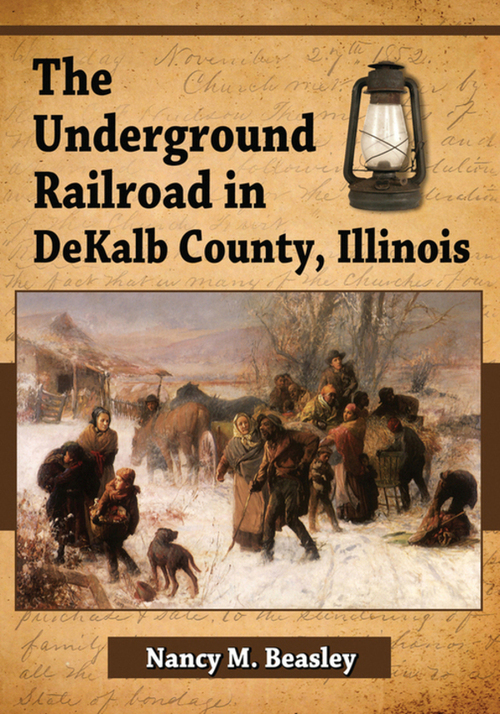

The Underground Railroad in DeKalb County, Illinois

NANCY M. BEASLEY

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Beasley, Nancy M., 1942

The underground railroad in DeKalb County, Illinois / Nancy M. Beasley.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7864-7200-0

1.Underground RailroadIllinoisDeKalb County.2.Fugitive slavesIllinoisHistory19th century.3.DeKalb County (Ill.)History19th century.I.Title.

F547.D3B43 2013

975.8'22503dc232012051478

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

2013 Nancy M. Beasley. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any formor by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopyingor recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: artwork The Underground Railroad, 1893 ( 2013 PicturesNOW); lantern ( 2013 Shutterstock); background letter Sycamore Congregationalist 1852 Resolution outlining displeasure with slavery

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my husband, George Franklin Beasley

Acknowledgments

My profound gratitude and praise:

To Phyllis Kelley (19242011), DeKalb County historian (19892011), with whom I shared a love of local history and who provided clues for research and details for the narrative. She read this manuscript before she died; her concise comment was, Its all there.

To the many anonymous volunteers at the Joiner History Room, in Sycamore, DeKalb County, Illinois, who checked county archives for obituaries and historical references.

To Francis ODonnell, archivist, Andover-Harvard Theological Library, with whom I had several enlightening telephone calls and who supplied photocopies of archival materials.

To Pat Michel, for her initial editing assistance and narrative suggestions.

To Jim Womack, professional photographer, for his invaluable assistance in the preparation of educational slides for public presentations of the subject matter.

To George Beasley, Bonita DeVale, Judy Eulburg, David Hankins, Virginia McComb, Lynne Miller, Jane Ann Moore, William Moore, Carole Murphy, Fay Stone, Nancy Wehlage and Gary Wehlage, who read all or part of the draft manuscript, for their questions and suggestions.

To my contemporary friends who endured the several years of my obsession with my old friends, the Abolitionists of DeKalb County, Illinois, the antislavery movement and its byproduct, the ever mysterious and still elusive Underground Railroad.

And to my husband, George. You believed in the project and provided encouragement during the long research and creative process. As the years of research and writing continued, you asked the ultimate motivational question, When are you going to nish?

I extend my humble thanks to you all.

Nancy M. Beasley

Preface

Several years ago I discovered the original 1840s handwritten minutes book of the First Congregational Church and Church Society in Sycamore, Illinois. The Congregationalists merged with the local Universalists in 1927 to become the Federated Church. What a treasure trove! Here were accounts of the public accusations and ecclesiastic trials of church members who had transgressed stated church rules of conduct. Occasionally a notation would direct the reader to a paper le, which unfortunately no longer exists. Evidence of Americas early Puritan ethics abounded in the owing cursive. As various names were repeated throughout the record, this resident historian asked questions. Who was Deacon David West, alleged to be active in the Underground Railroad? From what region did he come? In what state had he lived previously? What was his background?

My curiosity increased when I read about the Rev. Oliver W. Norton, who voluntarily ended his ministry at the First Congregational Church following several consecutive Church Society meetings at which his opinions about slavery were discussed. Norton was obviously antislavery. How did he happen to be in Sycamore, Illinois? Where did he go next?

The historian separates fact from ction. This study, however, compiles current known information, both facts and area folklore, regarding the antislavery movement and the Abolitionists in DeKalb County, Illinois. A preponderance of evidence combined with additional reading created background for the narrative. When the truth becomes legend, then the legends are what you recount. This includes regional beliefs pertaining to the Underground Railroad and has drawn on various written and oral historical sources. With the addition of information from previously unpublished documents, a clearer picture of the areas antislavery movement emerges.

Some of what was initially recorded may have been romanticized by the aging memories of those original Abolitionists. However, I cannot ignore the prevalent strong local oral traditions. Neither do I seek to create an alternative history. To neglect the fact that only white people were helping the fugitive slaves ee through DeKalb County would be to disregard the truth. This does not mean that I am overlooking any contemporary research about the brave African Americans who aided the thousands escaping slavery. It simply means that in the mid1800s in DeKalb County, Illinois, that avenue of assistance and guidance did not exist.

Because local sites and individuals can be connected to Underground Railroad activities through primary sources, the myths and legends surrounding DeKalb County activists acquire credibility.

To learn more about the antislavery advocates, it was necessary to research those individuals. Where did they come from? Why did they move to DeKalb County? Who were their family members? An appendix lists and describes the people in DeKalb County who were either active as Abolitionists, in the antislavery movement and/or in the Underground Railroad. Much of the information pertaining to vital statistics was drawn from census records plus secondary printed information, including obituaries and historical works. Subscriber lists for the antislavery newspaper Western Citizen and church membership rolls yielded valuable data. Family genealogists should treat the information as clue material only, and continue to research original documents containing vital statistics for verication.

The word Abolitionist used as a noun is purposely capitalized throughout when referring to the active antislavery citizenry of DeKalb County. They personally considered being an Abolitionist a badge of honor, akin to belonging to a church or a political party, and much deserved the elevated status. Unlike other geographical areas in both the Northern and Southern United States, DeKalb County Abolitionists were neither openly persecuted, nor publicly prosecuted. There are no reports of mob action by anti-abolitionists. There are no reports of proslavery riots. And there are no recorded incidents of civil action against the locals who disobeyed the Fugitive Slave Law. Privately, there may possibly have been subtle criticisms against the antislavery voices. However, the overriding factor was that the good citizens who were the church members, the antislavery activists, and the elected county ofcials were one and the same. There was no room for discord.

Next page