August 11, 1841

O N A HOT NIGHT IN A UGUST 1841, fugitive slave Frederick Douglass stood before a thousand white people inside a rickety wooden building in Nantucket, Massachusetts. A handful of Black people appeared in the crowd, but the group looked like a sea of white to Douglass. Accustomed to consider white men as my bitterest enemies, he later recalled, he trembled as he prepared to address them.

Not three years had passed since he had escaped from enslavement in Maryland. There is no spot on the vast domains over which waves the star-spangled banner where the slave is secure, Douglass would later explain. Go east, go west, go north, go south, he is still exposed to the bloodhounds that may be let loose against him. No fugitive slave was safe in the United Statesnot even at an abolitionist convention.

Nantucket Atheneum, where Douglass first spoke. Original illustration on paper by Mr. Samuel Haynes Jenks, ca. 1844. Courtesy of The Nantucket Atheneum.

And yet Douglass felt he had no choice about speaking up. He was already part of the movement that ran on words. His host, Quaker William Coffin, had brought him to this meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society after hearing Douglass speak at a Black church in New Bedford. Tell your story, Frederick, Coffin urged Douglass now, as the abolitionists waited. The strikingly handsome manstrong chin, chiseled mouth, and wide-set eyesusually dressed in a waistcoat, formal jacket, and high-collared white shirt, rose reluctantly to his feet.

Douglass never could remember what it was he said that evening.

Only the need for adjournment ended his debut appearance. The next day he was immediately invited to resume and spoke at even greater length. Although journalists from various antislavery publications attended the conference, there is no record of Douglasss remarks. But the reporters in the room agreed on one thing: Douglass brought down the house. Flinty hearts were pierced, Lydia Maria Child reported for the abolitionist newspaper National Anti-Slavery Standard, and cold ones melted by his eloquence. Our best pleaders for the slave held their breath for fear of interrupting him. Later, after Douglass had made countless speeches for the antislavery movement, some speculated that he might have performed one of his signature darkly humorous riffs that night in Nantucket, perhaps imitating a southern clergyman giving a self-righteous sermon about the virtues of slavery. He might even have resorted to song, warbling, Come saints and sinners, hear me tell,/How pious priests whip Jack and Nell,/And women buy and children sell,/Then preach all sinners down to hell,/And sing of heavenly union.

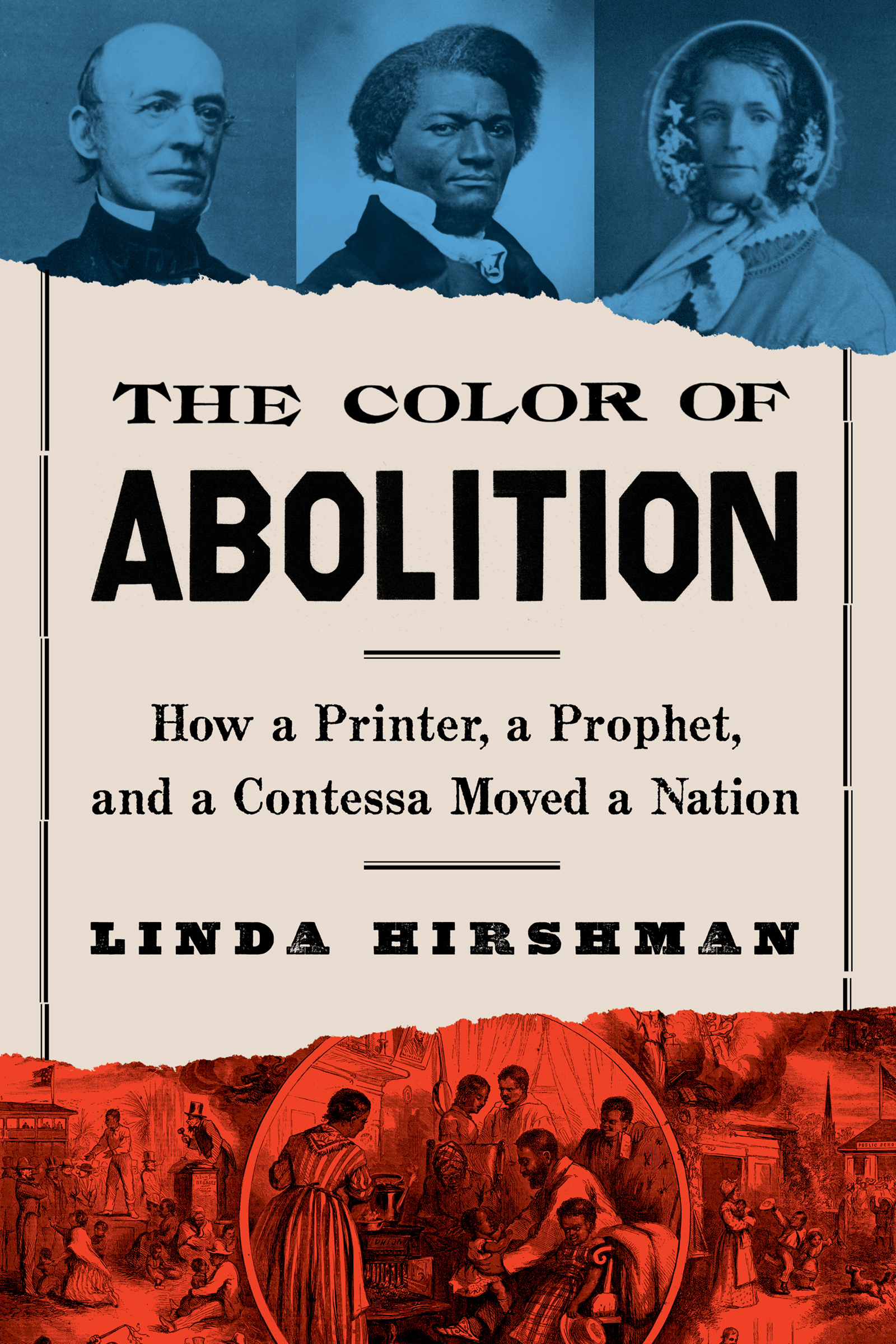

There is no scarcity of reportage about what came after Douglasss speech. William Lloyd Garrison, white editor and printer of the antislavery paper The Liberator and, at age thirty-five, the most prominent leader of the ten-year-old abolitionist movement, stood up to respond. As an orator, Garrison would certainly not equal Douglass, but at the time he was renowned in the antislavery movement. Never again would he rouse a crowd as he did after hearing Frederick Douglass for the first time that night.

Have we been listening to a thing? Garrison asked the crowd gathered in the Nantucket Atheneum. A piece of property, or to a man?

A man! A man! hundreds of voices replied.

And should such a man be held as a slave in a republican and Christian land? Garrison continued, his voice rising.

No, no! Never, never!

But it was 1841. Abolition seemed a distant prospect at best. So Garrison asked the only question his audience could actually do something about immediately.

Shall such a man ever be sent back to slavery from the old soil of Massachusetts?

No, no!

As the crowd shouted its refusal to send men back to slavery, Garrison reminded them of why they amplified their cry.

No! A thousand times no! Sooner the lightnings of heaven blast Bunker Hill monument till not one stone shall be left standing on another.

Garrisons reference to Bunker Hill was no accident. The battle, fought in the hills outside Boston in 1775, was one of the first engagements of the American Revolution. The rebellious colonists at Bunker Hill lost but inflicted unexpected losses on the superior forces of empire. An improbable and outnumbered ragtag army fighting for human freedom, the Americans of 1775 provide a poignant metaphor for the abolitionists. Birthed in freedom and enforcing slavery, America was cracked at the root. The abolitionists would argue countless times: if all men are created equal, then in the land of Bunker Hill, the man Frederick Douglass should never have been enslaved.

As soon as the meeting ended, John A. Collins, theology school dropout and now vice president and general agent for Garrisons Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, invited the newcomer to become an antislavery agent. Douglass would travel to the gatherings throughout eastern Massachusettsa lifeline in the small and beleaguered abolition movement in 1841and tell his story.

Although she was not present at Douglasss maiden appearance on Nantucket, Maria Weston Chapman, the beautiful, wealthy Bostonian from a prominent abolitionist family who de facto ran the Society office, would manage much of his new career. Weston Chapmannicknamed the Contessa by one of her admirerswas perhaps Garrisons closest comrade. Since the gorgeously dressed socialite had shocked people in the modest abolition world by walking into a meeting in 1834, her fashionable Boston town house had become the beating heart of the Society that fueled the movement.

The meeting on that remote Massachusetts island in August 1841 was a snapshot of the movement for the abolition of slavery. At the center of the picture was the fugitive, with his indelible story of life in the slave Souththe inexcusable wrongdoing at the heart of the American republic. The historian Manisha Sinha would later call these stories the movement literature of abolition. Then, the audience of white northerners, who had been gathering for over a decade to argue for the immediate, unambiguous abolition of slavery. Here and there, an embarrassingly few, but crucial, Black abolitionists, who had formed the backbone of the movement from the beginning. The action centered on Douglasss heart-piercing speech, reflecting the outsized power of rhetoric. The scene opened up the possibility of an alliance interracial and sex-integrated at the very topthe first such major public movement in the history of the nation. For twelve years this alliance worked to change the nation.

But as with all alliances, sooner or later the question would arise: Who gets what from the deal?

This is what breaks up alliances, however fruitful the collaboration. By 1853, the partnership of Garrison, Douglass, and Weston Chapman was done. The creation, duration, and impact of their alliance to abolish slavery is the subject of this book.

The strains on the interracial aspect of the enterprise of Douglass and the mostly white New England abolitionists were visible already in Nantucket. Later, when Douglass was the most popular and renowned speaker in a movement that lived on words, his appearance that night in 1841 became a legend. At the time, however, Garrison took only passing notice of the slaves debut in