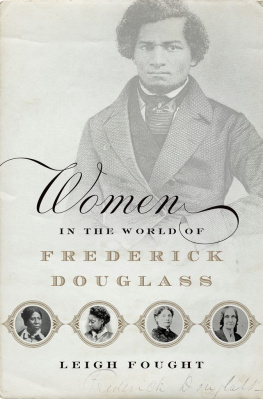

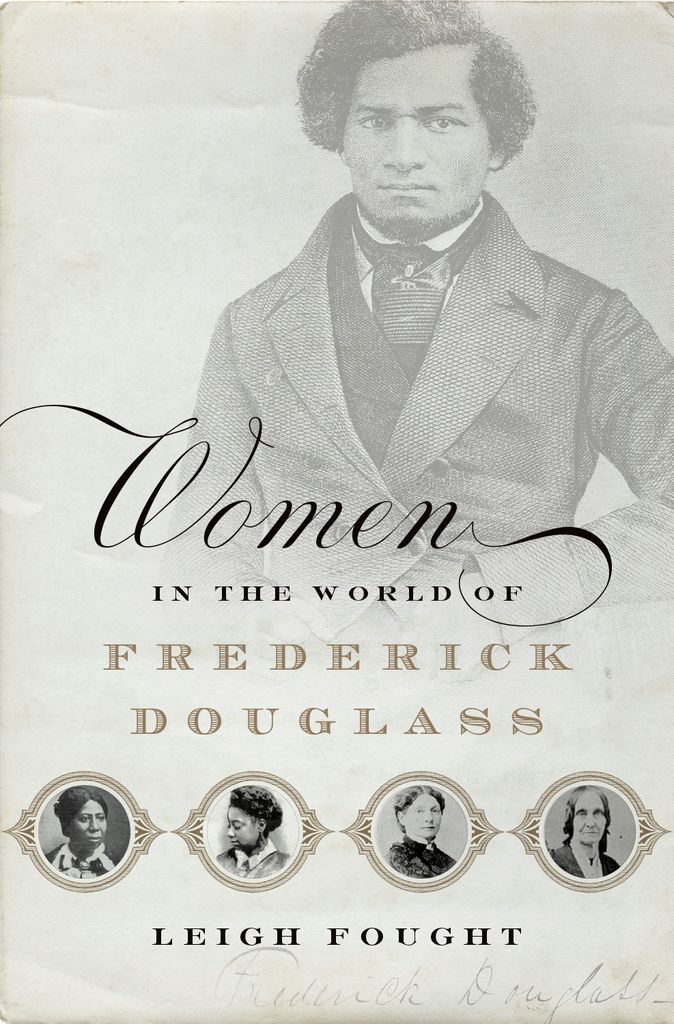

Women in the World of Frederick Douglass

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fought, Leigh, 1967 author.

Title: Women in the world of Frederick Douglass / Leigh Fought.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2017. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016042212 (print) | LCCN 2016045837 (ebook) | ISBN 9780199782376 (hardback) | ISBN 9780199782611 (Updf) | ISBN 9780190627287 (Epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Douglass, Frederick, 18181895Relations with women. | African American abolitionistsBiography.

Classification: LCC E449.D75 F68 2017 (print) | LCC E449.D75 (ebook) | DDC 973.8092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016042212

For the men of my world:

Louis, Karl, Keith, Jake, Bradley,

and, most of all,

Doug

CONTENTS

Although the writing of a book often takes place in solitude, books themselves do not go from an idea to an object in a readers hand without the collaboration and influence of multitudes. In thanking my multitude, I must also tell the story of how Women in the World of Frederick Douglass came to fruition. The seed of this book was planted during my time as an associate editor at the Frederick Douglass Papers in the early 2000s at Indiana UniversityPurdue University at Indianapolis. I was very happy to have worked there because I became a better researcher and found myself embroiled in the life of one of historys most fascinating characters. Mark Emerson, Rachael Drenovsky, Candy Hudziak, and Diane Barnes spent many hours with me mining and opining upon the details of Douglasss life for the first correspondence volume, while Robin Condon saw the project to completion. During those years, I had envisioned this book as a series of biographical chapters focused on particular women. Nah, no one is interested in them, my friend Babu Srinivasan told me. Make it about the thing that connects them all. Babu counseled me through my first book, and he is also one of the smartest people anyone could ever want to know, with the Jeopardy! credentials to prove it. I listened. His suggestion to reconceptualize the book made it far more interesting to far more people.

Then, I took a few detours. The way back to Douglass wandered through the blogosphere. There, my pseudonymous avatar met many wonderful scholars also exploring the creative freedom that comes with adopting a slightly different persona than allowed in their usual lives. They formed a community of intellectual possibility that allowed me not only to articulate the idea for this book, but to also see it as something other people might actually want to read. For that, I will always value Historiann, Digger, Feminist Avatar, Belle, Ink, Bittersweet Girl, RPS77, Claire, Susan in comments, Squadratomagico, FeMOMist, GayProf, Notorious PhD, and others whom I am certain to have forgotten in name if not in spirit.

When I finally found the gumption to write a proposal and submit it to someone with clout, Susan Ferber at Oxford University Press seized it. She did not mind my frantic call when I nearly missed our first appointment due to the DC Metros business as usual, and the contract that she offered gave the project legitimacy when I was applying for funding and jobs. She has been more than patient as my job changes, moves, and health delayed progress and the research revealed a much more complex story than I originally anticipated. Her comments forced this to be a better book, and she will be remembered among the great editors of our time. Her colleagues behind the scenes at Oxford University Press have also made this volume come to life beautifully.

Susan also chose some fantastic external evaluators for both the proposal and manuscript. Two remained anonymous, although their comments were useful and supportive. Catherine Clinton, who read the proposal, is a model of generosity. As I have admired her career since I first read Plantation Mistress back in graduate school, so she has helped mine from my first book, to the comments that she made on papers I gave at a Frederick Douglass conference in 2005 and a British American Nineteenth Century Historians conference in 2009, to writing for my tenure. I only wish I could be as grand as her one day. I would have guessed that Nancy Hewitt had read the full manuscript if she had not revealed herself because no one knows so much about the lovely Amy Post as she. Nancy gave incredible suggestions that helped me reshape three frustrating chapters into something much more coherent and, indeed, intelligent than they otherwise might have been.

The National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Research Stipend allowed me to research for weeks in the Post and Porter Family Papers in Rochester, the Rochester Ladies Antislavery Society Papers in Ann Arbor, the Amy Kirby Post Papers at Swarthmore, and the Walter O. Evans Collection in Savannah. Vice President Paula Matusky and Nancy Newell in the grants office at Montgomery College in Takoma Park, Maryland, where I worked at the time, officially nominated me for the award. Then Dean J. Barron Boyd orchestrated my move to Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York, where the Research and Development Committee, chaired by Julie Olin-Ammentorp, helped defray the costs of photographic images.

Having earned a library science degree and worked as an archivist myself during one of those professional detours, I have a great appreciation for the work, procedures, and nuisances encountered by those who make collections available to researchers. I wish I could name everyone who brought me yet another box or folder, or who answered another in a series of obtuse questions. Wayne Stevens, who handles Interlibrary Loan for faculty at Le Moyne College, could find Amelia Earhart if I put in a request. Lori Birrell, Melinda Wallington, and their staff in the Rare Books and Manuscripts Collections in the Rush Rhees Library at the University of Rochester have created a wonderful online exhibit of the Amy and Isaac Post Papers and still remember my work there with enthusiasm. Eric Frazier helped me through the Antislavery Collection at the Boston Public Library and spoke with me about becoming an archivist when the seed of this book had not yet germinated. He reappeared when I contacted the Library of Congress about images. Marilyn Nolte of the Friends of Mt. Hope was more than generous with information and records about the Douglass burial site, in spite of my initial, inexcusable snappishness. The librarians at the Jagiellonian Library in Krakow, Poland, had great patience with an American who did not understand the monetary conversion figures and willingly scanned almost an entire series from the Varnhagen von Ense Collection. My gratitude also goes to the staffs at the Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Mt. Holyoke College Archives in Massachusetts, the Bird Library in Syracuse, the Lynn Museum and Historical Society, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, the Talbot County Historical Society, the Talbot County Public Library, the Maryland Historical Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Onondaga Historical Society, the town clerks office in Honeoye, the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, the American Antiquarian Society, the Archives of American Art, Colgate University and its database of the American Missionary Association Archives, the Hall of Records Commission at the Maryland State Archives, the Houghton Library at Harvard University, the Nebraska State Historical Society, Smith College Special Collections, and the Butler Library at Columbia University.