Today, once again, the original Constitution is being vilified, as a validation of slavery, by people with disreputable agendas and negligible understanding. Damon Root, who explicates the great document as well as anyone writing today, brings the patience of Job and a noble allyFrederick Douglassto the task of refuting this recycled canard. Root and Douglass, like root beer and ice cream, are an irresistible American combination.

George F. Will

Is the Constitution an antislavery glorious liberty document or a proslavery agreement with hell? The antebellum debates between William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass are as relevant today as they were two centuries ago. In this important new book, Damon Root methodologically and accessibly walks you through this formative constitutional debate and shows why Douglass rightfully belongs in the pantheon of American civic philosophers.

Josh Blackman, professor of constitutional law at South Texas College of Law Houston

Damon Root has written a meticulously researched celebration of the intellectual legacy of Frederick Douglass.... As we continue to debate the legacy of slavery, Root convincingly argues that in reconciling the countrys most profound moral incongruitythat a nation purporting to be a beacon of liberty could be so inextricably rooted in human bondageDouglass should be mentioned in the same breath as the Founding Fathers, perhaps even more so, as a historical figure who not only championed the ideas that made America great, but in pointing out where it fell short of those values demanded that the country become a better version of itself.

Radley Balko, investigative journalist at the Washington Post and coauthor of The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist: A True Story of Injustice in the American South

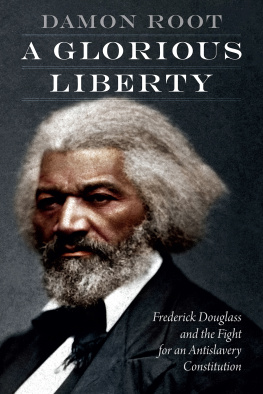

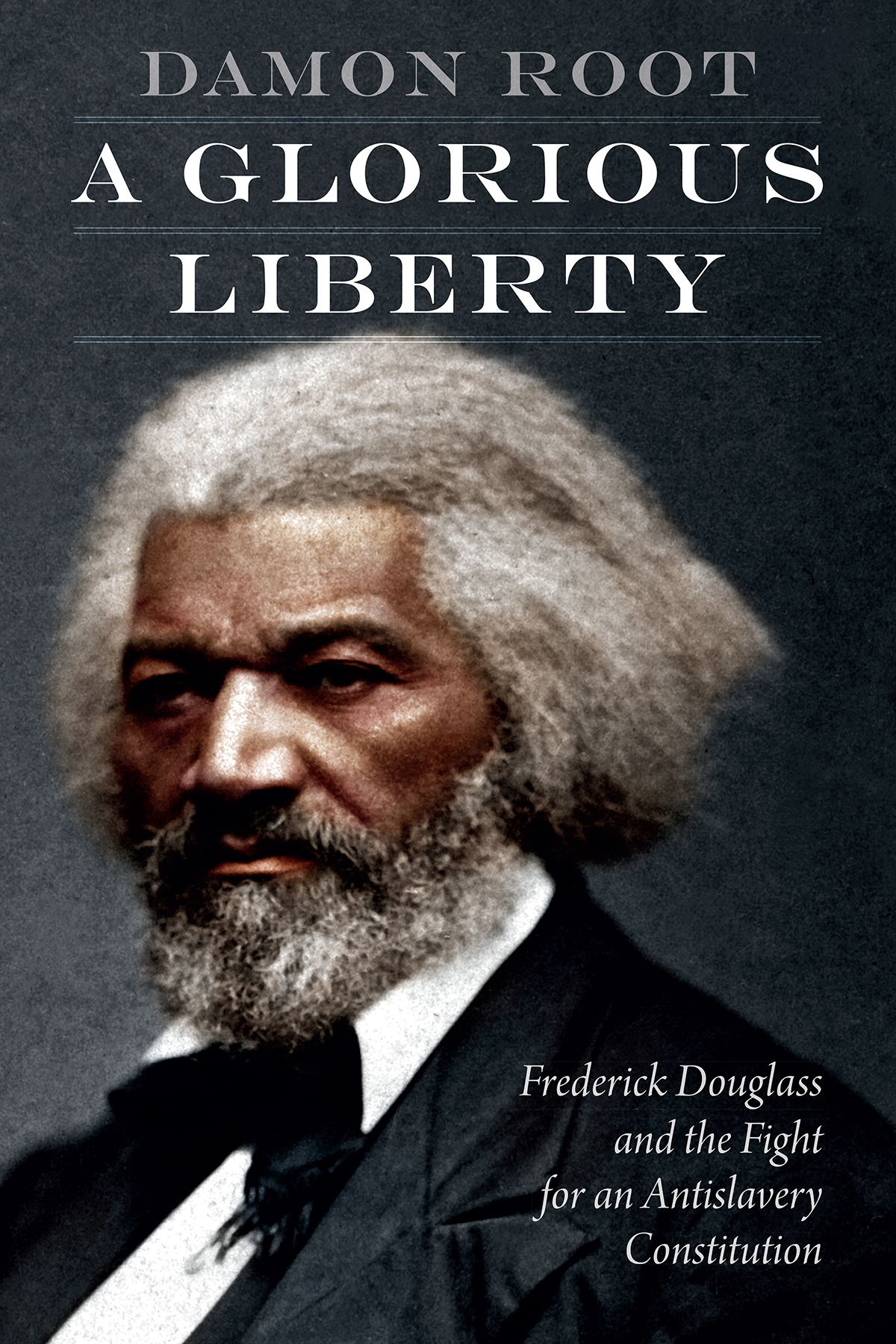

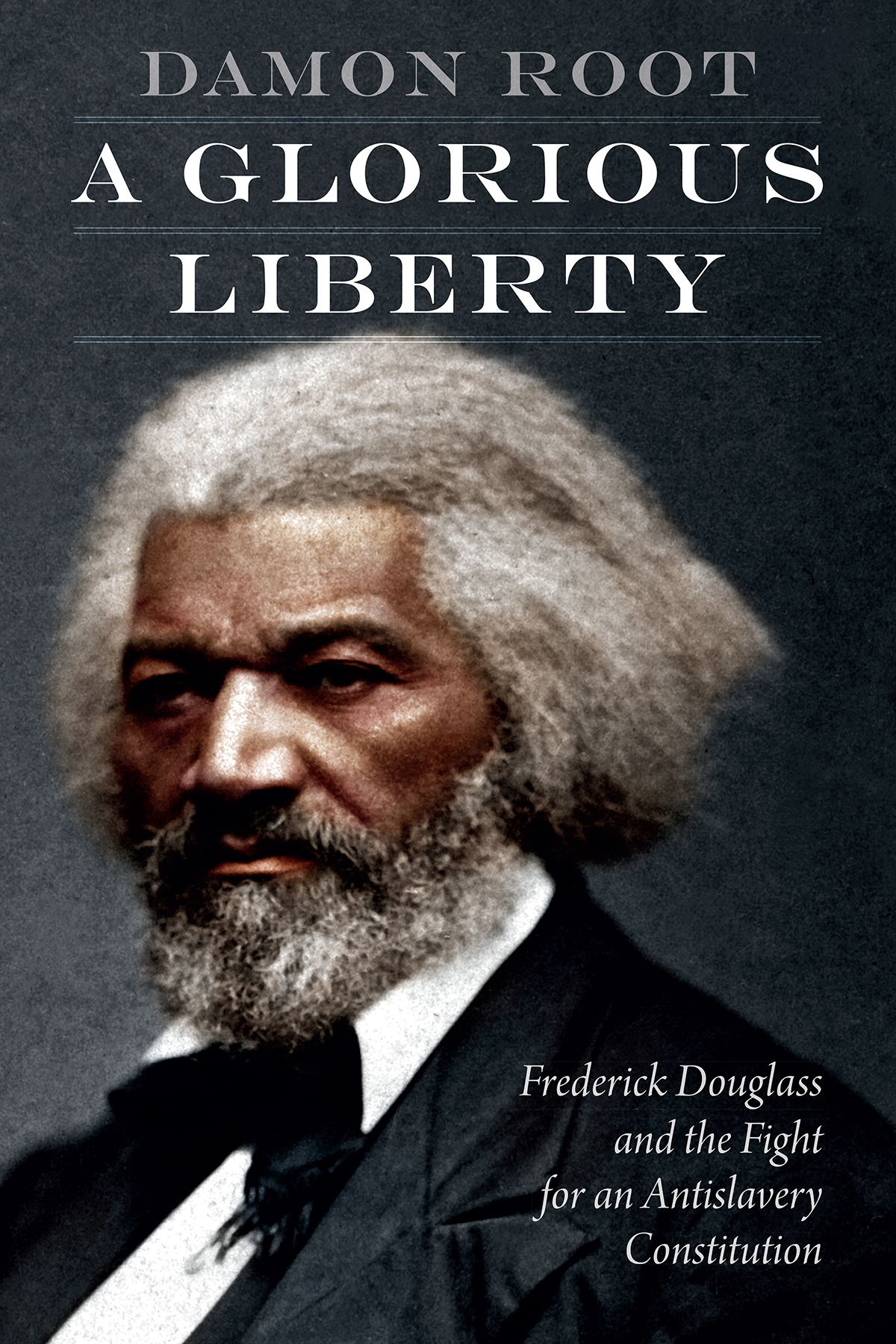

A Glorious Liberty

Frederick Douglass and the Fight for an Antislavery Constitution

Damon Root

Potomac Books

An imprint of the University of Nebraska Press

2020 by Damon Root

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image: Frederick Douglass, hand-colored photograph Mads Madsen.

Author photo by Reg Saner.

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Root, Damon, author.

Title: A glorious liberty: Frederick Douglass and the fight for an antislavery constitution / Damon Root.

Other titles: Frederick Douglass and the fight for an antislavery constitution

Description: Lincoln: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019058143

ISBN 9781640122352 (hardback)

ISBN 9781640123816 (epub)

ISBN 9781640123823 (mobi)

ISBN 9781640123830 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Douglass, Frederick, 18181895. | United States. Constitution. 13th Amendment. | United States. Constitution. 14th Amendment. | United States. Constitution. 15th Amendment. | Antislavery movementsUnited StatesHistory19th century. | African American abolitionists. | AbolitionistsUnited States. | Constitutional historyUnited States.

Classification: LCC E 449. D 75 R 66 2020 | DDC 973.8092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019058143

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Allison and Zoe

Contents

Frederick Douglasss Constitution

On May 9, 1851, the leading lights of the abolitionist movement gathered in Syracuse, New York, for the eighteenth annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Among the items on the agenda was a resolution calling for the society to officially recommend several antislavery publications, including a small weekly called the Liberty Party Paper. But William Lloyd Garrison, the powerful editor of the Liberator, one of abolitionisms flagship publications, would have none of that. The Liberty Party Paper, Garrison complained, saw the Constitution as an antislavery document. That view was tantamount to heresy, as it clashed with Garrisons famous judgment that the Constitution was a proslavery covenant with death and an agreement with hell. So a more congenial resolution was soon proposed: the American Anti-Slavery Society would only recommend those publications that toed the Garrisonian line.

It was at this point that Frederick Douglass stood up. An escaped former slave, an internationally acclaimed orator, and the author of a widely celebrated autobiography, Douglass cut a commanding figure in the abolitionist ranks. And for the previous ten years, he had been a friend, an ally, even a self-declared disciple of Garrisons. Every week the Liberator came, and every week I made myself master of its contents, Douglass later recalled. I not only likedI loved this paper, and its editor.

Those words went down about as well as might have been expected given the audience. There were howls of outrage, cries of censure. Garrison, for his part, accused Douglass of harboring ulterior (read, financial) motives. There is roguery somewhere! Garrison exclaimed. Douglass never quite forgave his old comrade for that.

In truth, Douglass agonized over his change of opinion. His came around gradually and only after much brooding. He forced himself to re-think the whole subject, he recalled, and to study, with some care, not only the just and proper rules of legal interpretation, but the origin, design, nature, rights, powers, and duties of civil government, and also the relations which human beings sustain to it.

Those studies began to produce fruit as early as 1849. Writing in the North Star on March 16 of that year, Douglass conceded that the Constitution is not a proslavery instrument when interpreted standing alone, and construed only in the light of its letter. The trouble came when he considered the proslavery opinions of the men who framed and adopted it. How to reconcile the text of the Constitution with the unwritten intentions of its framers?

A year later, on April 5, 1850, Douglass moved a little further away from the strict Garrisonian position. The Constitution is at war with itself, he now wrote. Liberty and Slaveryopposite as Heaven and Hellare both in the Constitution. Both in the Constitution? The imperious Garrison would not like the sound of that. Furthermore, Douglass ventured, if we adopt the preamble [to the Constitution], with Liberty and Justice, we must repudiate the enacting clauses, with Kidnapping and Slavery.

By 1851 his mind was made up. Yes, the Constitution did contain certain oblique references to slavery, such as the notorious Three-Fifths Clause, which said that for purposes of taxation and political representation, state populations would be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. But that clause, and the handful of others like it, spoke only in the ambiguous language of persons. Neither the word slave nor the word slavery appeared anywhere in the text of the Constitution. That textual absence, Douglass concluded, was a fatal weakness in the slaveholders position that must be exploited. Take the Constitution according to its plain reading, he insisted. I defy the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it. On the other hand, it will be found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery. In the years to come, Douglass would deploy those principles and purposes against the peculiar institution until it was finally destroyed.

Next page