ORWELLS COUGH

ORWELLS COUGH

Diagnosing the Medical Maladies and Last Gasps of the Great Writers

JOHN ROSS

A Oneworld Book

First published in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth

by Oneworld Publications 2012

Published in the United States by St.Martins Press,

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 USA, 2012

Copyright 2012 John J. Ross

The moral right of John J. Ross to be identified as the

Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-85168-951-4

ebook ISBN 978-1-78074-113-0

Cover design by Iain McIntosh

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books,

special offers, and exclusive content from

Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

For Megan

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

In the year 2000, the youth of America grew weary of inhibition and restraint. Rates of syphilis infection, which had fallen to all-time lows in the United States, began to spike upward. The first generation to reach sexual maturity in an era of effective, if onerous, treatment for HIV infection was blas about the threat of AIDS, leading to an increase in high-risk sexual activity. This indifference was abetted by the more efficient market for anonymous sex made possible by the Internet, as well as advances in amateur pharmacology that made crystal meth cheap and abundant.

At the Boston teaching hospital where I then worked as an infectious diseases specialist, several patients presenting with secondary syphilis initially went unrecognized. Syphilis, which affected half a million Americans in 1945, had become such a rare disease that many U.S. physicians had never seen a case, and were unfamiliar with its manifestations. I put together a PowerPoint talk on syphilis for medical grand rounds, and thought to tart it up with a few Shakespeare quotations, having a vague recollection from my undergraduate days that the Bard was fond of joking about the great pox. I dusted off my battered copy of the Riverside Shakespeare and started leafing through it. Holy crap, I thought, there is a lot of stuff here on syphilis. My curiosity was piqued, and I did some more digging. Was there a connection between Shakespeares syphilitic obsession, contemporary gossip about his sexual misadventures, and the only medical fact known about him with certaintythat his handwriting became tremulous in late middle age? I wrote an article that appeared in Clinical Infectious Diseases, supposing it to be of scant interest beyond its immediate specialty audience. To my surprise, it generated a fair amount of Internet buzz, and inspired a segment on Jon Stewarts satirical U.S. television programme, The Daily Show. I began to think that there might be interest in a book on the topic of writers and disease, written from a medical perspective.

I have taken the liberty of beginning the chapters on Shakespeare, Milton, Swift, Joyce, and Orwell with vignettes that are intended to convey the experience of illness from the point of view of the patient. Those that concern Milton, Swift, and Orwell are firmly rooted in biography. The Shakespeare vignette is entirely conjectural. Joyce is known to have been diagnosed with gleet, or gonorrhoea, and he was directed to receive treatment from a Dublin practitioner with expertise in this condition. The imagined and rather graphic gonorrhoea treatment described in this chapter is based on state-of-the-art medical care in 1904. The physicians MIntosh and Mellor are fictional.

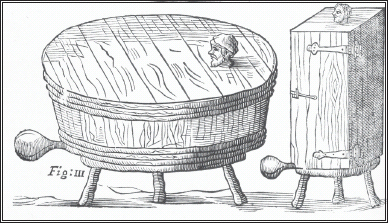

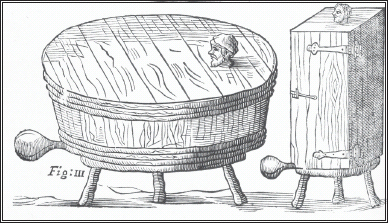

Sweating tubs used in the seventeenth-century treatment of syphilis. (The Royal Society)

1. THE HARDEST KNIFE ILL-USED:

Shakespeares Tremor

The real mystery of Shakespeare, a thousand times more mysterious than any matter of the will, is: why is it thatunlike Dante, Cervantes, Chaucer, Tolstoy, whomever you wishhe makes what seems a voluntary choice to stop writing?

Harold Bloom

In Shakespeares tomb lies infinitely more than Shakespeare ever wrote.

Herman Melville, Hawthorne and His Mosses

Twenty years he lived in London... Twenty years he dallied there between conjugal love and its chaste delights and scortatory love and its foul pleasures.

James Joyce, Ulysses

His fitful fever returned. Master Shakespeare pulled the hood of his cloak down low over his eyes and hurried from his lodgings in Bishopsgate, walking as quickly as he could on his hobbled legs. He awkwardly dodged a pair of rambling pigs and picked his way through the dung and muck of the city streets. The stench and filth rarely troubled him now, as they had when he first came here from the country. Nearer the bridge, the clamour of the city increased: the clatter of carts, the cries of street peddlers, the gossip of alewives, the drunken braggadocio of London gallants. A black-clad Puritan surveyed the scene sourly and made brief eye contact with Will. The player hung his head and balled his hands into fiststo hide the telltale rash on his palms.

London Bridge was marvellous and strange, a massive structure built over with splendid houses. With relief he entered the dark, claustrophobic tunnel beneath the dwellings. Inside, a continual roar of noise: the tidal rush of water between the ancient piers; waterwheels creaking; apprentices brawling; carters disputing the right-of-way; a blind fiddler playing; sheep bleating on their way to Eastcheap, bound for slaughter. He left the shelter of the bridge, and emerged into painful sunlight on the other side. His shins throbbed and his muscles ached. In spite of himself, he peered up at the great stone gate at the end of the bridge, adorned with traitors heads on pikes. Shreds of mouldy flesh clung to the grinning skulls, their tattered hair bleached by sun and rain.

In Southwark, he heard the barking mastiffs and the howling crowd at the Bear Garden. He imagined old Sackerson the bear bellowing, lashing out with his claws, chained to a post, set on by dogs. A glimpse of ragged children playing in an alley filled him with thoughts of home and a pang of loneliness and shame. Before a row of brothels he saw a scabby beggar-woman with sunken nose and ulcerated shins. After years of faithful service in the stews, she has been turned out in the street to die of the pox. A chill of fear ran up his spine, and he looked away.

There was a pounding in his head and he felt dull and stupid. He circled many times through a maze of flyblown houses before he stumbled on the place. A servant showed him down a set of stairs. The bard descended into a hot cellar reeking of sulphur. A vast oven filled the room with flickering orange light. The sweaty heads of groaning men peered out from large wooden tubs. But the tubs were not filled with water. A sallow and emaciated man carrying iron tongs scurried round, feeding hot bricks into the tubs through a trapdoor. He poured vinegar onto the heaps of bricks and acrid steam rose up, making the glistening men within moan and shake.